Res judicata

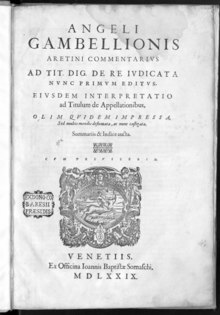

Res judicata or res iudicata, also known as claim preclusion, is the Latin term for judged matter,[1] and refers to either of two concepts in common law civil procedure: a case in which there has been a final judgment and that is no longer subject to appeal; and the legal doctrine meant to bar (or preclude) relitigation of a claim between the same parties.

The doctrine of res judicata is a method of preventing injustice to the parties of a case supposedly finished but perhaps also or mostly a way of avoiding unnecessary waste of judicial resources.

However, a different offense may be charged on identical evidence at a second trial; whereas, res judicata precludes any causes of action or claims that may arise from the previously litigated subject matter.

In that case res judicata would not be available as a defence unless the defendant could show that the differing designations were not legitimate and sufficient.

The scope of an earlier judgment is probably the most difficult question that judges must resolve in applying res judicata.

[7] US Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart explained the need for this legal precept as follows:Federal courts have traditionally adhered to the related doctrines of res judicata (claim preclusion) and collateral estoppel (issue preclusion).

[8]Res judicata does not restrict the appeals process,[9] which is considered a linear extension of the same lawsuit as the suit travels up (and back down) the appellate court ladder.

Once the appeals process is exhausted or waived, res judicata will apply even to a judgment that is contrary to law.

There are limited exceptions to res judicata that allow a party to attack the validity of the original judgment, even outside of appeals.

Res judicata may be avoided if claimant was not afforded a full and fair opportunity to litigate the issue decided by a state court.

When a subsequent court fails to apply res judicata and renders a contradictory verdict on the same claim or issue, if a third court is faced with the same case, it will likely apply a "last in time" rule, giving effect only to the later judgment, even though the result came out differently the second time.

Additionally, under Article 38 (1)(c) of the same statute, it is considered a "general principle of law recognized by civilized nations".