Classical sculpture

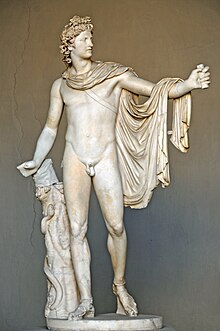

In particular, the male figures of Archaic Greece tended to be represented in the nude, while this was uncommon during all periods of ancient Egyptian art (except when slaves or enemies were depicted).

[4] Though the statue itself is lost to history, its principles manifest themselves in the Doryphoros ("spear-bearer"), which adopted extremely dynamic and sophisticated contrapposto in its cross-balance of rigid and loose limbs.

Common people, women, children, animals and domestic scenes became acceptable subjects for sculpture, which was commissioned by wealthy families for the adornment of their homes and gardens.

Realistic portraits of men and women of all ages were produced, and sculptors no longer felt obliged to depict people as ideals of beauty or physical perfection.

The strengths of Roman sculpture are in portraiture, where they were less concerned with the ideal than the Greeks or Ancient Egyptians, and produced very characterful works, and in narrative relief scenes.

Latin and some Greek authors, particularly Pliny the Elder in Book 34 of his Natural History, describe statues, and a few of these descriptions match extant works.

While a great deal of Roman sculpture, especially in stone, survives more or less intact, it is often damaged or fragmentary; life-size bronze statues are much more rare as most have been recycled for their metal.

[5] Most statues were actually far more lifelike and often brightly coloured when originally created; the raw stone surfaces found today is due to the pigment being lost over the centuries.

During the Roman Republic, it was considered a sign of character not to gloss over physical imperfections, and to depict men in particular as rugged and unconcerned with vanity: the portrait was a map of experience.

Ancient statues and bas-reliefs survive showing the bare surface of the material of which they are made, and people generally associate classical art with white marble sculpture.

[7][8] A travelling exhibition of 20 coloured replicas of Greek and Roman works, alongside 35 original statues and reliefs, was held in Europe and the United States during 2007–2008, Gods in Color: Painted Sculpture of Classical Antiquity.

[9] Details such as whether the paint was applied in one or two coats, how finely the pigments were ground, or exactly which binding medium would have been used in each case—all elements that would affect the appearance of a finished piece—are not known.

Because of the relative durability of sculpture, it has managed to survive and continue to influence and inform artists in varying cultures and eras, from Europe to Asia, and today, the whole world.

While classical art gradually fell into disfavor in Europe after the fall of the Western Roman Empire, its rediscovery during the early Italian Renaissance proved decisive.