Claude Lévi-Strauss

Gustave Claude Lévi-Strauss was born in 1908 to French-Jewish (turned agnostic) parents who were living in Brussels, where his father was working as a portrait painter at the time.

[9] In his last year (1924), he was introduced to philosophy, including the works of Marx and Kant, and began shifting to the political left (however, unlike many other socialists, he never became communist).

He accompanied Dina, a trained ethnographer in her own right, who was also a visiting professor at the University of São Paulo, where they conducted research forays into the Mato Grosso and the Amazon Rainforest.

In the 1980s, he discussed why he became vegetarian in pieces published in Italian daily newspaper La Repubblica and other publications anthologized in the posthumous book Nous sommes tous des cannibales (2013):A day will come when the thought that to feed themselves, men of the past raised and massacred living beings and complacently exposed their shredded flesh in displays shall no doubt inspire the same repulsion as that of the travellers of the 16th and 17th century facing cannibal meals of savage American primitives in America, Oceania, Asia or Africa.Lévi-Strauss returned to France in 1939 to take part in the war effort and was assigned as a liaison agent to the Maginot Line.

After the French capitulation in 1940, he was employed at a lycée in Montpellier, but then was dismissed under the Vichy racial laws (Lévi-Strauss's family, originally from Alsace, was of Jewish ancestry).

A series of voyages brought him, via South America, to Puerto Rico, where he was investigated by the FBI after German letters in his luggage aroused the suspicions of customs agents.

Along with Jacques Maritain, Henri Focillon, and Roman Jakobson, he was a founding member of the École Libre des Hautes Études, a sort of university-in-exile for French academics.

[23] This intimate association with Boas gave his early work a distinctive American inclination that helped facilitate its acceptance in the U.S. After a brief stint from 1946 to 1947 as a cultural attaché to the French embassy in Washington, DC, Lévi-Strauss returned to Paris in 1948.

[26] In a similar vein, a statement by Lévi-Strauss was broadcast on National Public Radio in the remembrance produced by All Things Considered on 3 November 2009: "There is today a frightful disappearance of living species, be they plants or animals.

"[citation needed] The Daily Telegraph said in its obituary that Lévi-Strauss was "one of the dominating postwar influences in French intellectual life and the leading exponent of Structuralism in the social sciences".

Lévi-Strauss supposedly suggested that the English title be Pansies for Thought, borrowing from a speech by Ophelia in Shakespeare's Hamlet (Act IV, Scene V).

Briefly, he considers culture a system of symbolic communication, to be investigated with methods that others have used more narrowly in the discussion of novels, political speeches, sports, and movies.

The English anthropologist Alfred Reginald Radcliffe-Brown, who had read and admired the work of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, argued that the goal of anthropological research was to find the collective function, such as what a religious creed or a set of rules about marriage did for the social order as a whole.

Malinowski said, for example, that magic beliefs come into being when people need to feel a sense of control over events when the outcome is uncertain.

It results in a chart that is far more difficult to understand than the original data and is based on arbitrary abstractions (empirically, fathers are older than sons, but it is only the researcher who declares that this feature explains their relations).

Even though Lévi-Strauss frequently speaks of treating culture as the product of the axioms and corollaries that underlie it, or the phonemic differences that constitute it, he is concerned with the objective data of field research.

There is a big difference between the two situations, in that the kinship structure involving the classificatory kin relations allows for the building of a system which can bring together thousands of people.

He believed that modern life and all history were founded on the same categories and transformations that he had discovered in the Brazilian backcountry—The Raw and the Cooked, From Honey to Ashes, The Naked Man (to borrow some titles from the Mythologiques).

He argued for a view of human life as existing in two timelines simultaneously, the eventful one of history and the long cycles in which one set of fundamental mythic patterns dominates and then perhaps another.

In this respect, his work resembles that of Fernand Braudel, the historian of the Mediterranean and 'la longue durée,' the cultural outlook and forms of social organization that persisted for centuries around that sea.

He was only interested in the formal aspects of each story, considered by him as the result of the workings of the collective unconscious of each group, which idea was taken from the linguists, but cannot be proved in any way although he was adamant about its existence and would never accept any discussion on this point.

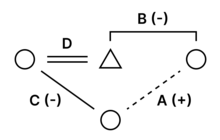

Influenced by Hegel, Lévi-Strauss believed that the human mind thinks fundamentally in these binary oppositions and their unification (the thesis, antithesis, synthesis triad), and that these are what makes meaning possible.

"[40] Laurie suggests that for Levi-Strauss, "operations embedded within animal myths provide opportunities to resolve collective problems of classification and hierarchy, marking lines between the inside and the outside, the Law and its exceptions, those who belong and those who do not.

According to this more basic theory, universal laws govern all areas of human thought: If it were possible to prove in this instance, too, that the apparent arbitrariness of the mind, its supposedly spontaneous flow of inspiration, and its seemingly uncontrolled inventiveness [are ruled by] laws operating at a deeper level...if the human mind appears determined even in the realm of mythology, a fortiori it must also be determined in all its spheres of activity.

In comparison to the true craftsman, whom Lévi-Strauss calls the Engineer, the Bricoleur is adept at many tasks and at putting preexisting things together in new ways, adapting his project to a finite stock of materials and tools.

However, both live within a restrictive reality, and so the Engineer is forced to consider the preexisting set of theoretical and practical knowledge, of technical means, in a similar way to the Bricoleur.

Diamond further remarks that "the Trickster names 'raven' and 'coyote' which Lévi-Strauss explains can be arrived at with greater economy on the basis of, let us say, the cleverness of the animals involved, their ubiquity, elusiveness, capacity to make mischief, their undomesticated reflection of certain human traits.

"[42]: 311 Finally, Lévi-Strauss's analysis does not appear to be capable of explaining why representations of the Trickster in other areas of the world make use of such animals as the spider and mantis.

Edmund Leach wrote that "The outstanding characteristic of his writing, whether in French or English, is that it is difficult to understand; his sociological theories combine baffling complexity with overwhelming erudition.

[44] Drawing on postcolonial approaches to anthropology, Timothy Laurie has suggested that "Lévi-Strauss speaks from the vantage point of a State intent on securing knowledge for the purposes of, as he himself would often claim, salvaging local cultures...but the salvation workers also ascribe to themselves legitimacy and authority in the process.