Claude Nicolas Ledoux

[3] His most ambitious work was the uncompleted Royal Saltworks at Arc-et-Senans, an idealistic and visionary town showing many examples of architecture parlante.

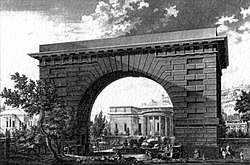

[4] Conversely his works and commissions also included the more mundane and everyday architecture such as approximately sixty elaborate tollgates around Paris in the Wall of the General Tax Farm.

On leaving the Collège, age 17, he took employment as an engraver but four years later he began to study architecture under the tutelage of Jacques-François Blondel, for whom he maintained a lifelong respect.

These two eminent Parisian architects designed in both the restrained French Rococo manner, known as the "Louis XV style" and in the "Goût grec" (literally "Greek taste") phase of early Neoclassicism.

However, under the tutelage of Contant d'Ivry and Chevotet, Ledoux was also introduced to Classical architecture, in particular the temples of Paestum, which, along with the works of Palladio, were to influence him greatly.

One of Ledoux's first patrons was the Baron Crozat de Thiers, an immensely wealthy connoisseur who commissioned him to remodel part of his palatial town house in the Place Vendôme.

A friend from Champagne, Joseph Marin Masson de Courcelles, found him a position as the architect for the Water and Forestry Department.

[6] The owner Franz-Joseph d'Hallwyll (a Swiss colonel) and his wife, Marie-Thérèse Demidorge, were anxious to ensure work was executed economically.

However, the limitations of the site made this impossible, so Ledoux resorted to trompe-l'œil painting a colonnade on the blind wall of the neighboring convent, thus extending the perspective.

Today the panelling from the salon, an early example of the neoclassical style, largely carved by Joseph Métivier and Jean-Baptist Boiston to the designs of Ledoux, is preserved in the Carnavalet Museum, Paris.

From this point Ledoux worked often in the Palladian style, usually employing a cubic design broken by a prostyle portico which gave an air of importance even to a small structure.

Through this interest in civic and municipal architecture and due, in no small part, to the notorious influence of Madame du Barry, Ledoux was commissioned with the modernization of the Salines de l'Est (Eastern Saltworks).

Close to the first of these sites, the Fermiers Généraux decided to explore a more mechanized and efficient method of extraction, by constructing a purpose-built factory near the forest of Chaux, in the Val d'Amour.

For the following decades, the salt works lay in decay until they were named a UNESCO world heritage site and refurbished as a local cultural center.

However, if the neoclassical hints to the exterior was regarded as modern then the interior was a revolution – venues for public entertainment were rare in the French provinces,[citation needed] and where they did exist it was traditional that only the nobles had seating, while those of less exulted rank had stood.

However Ledoux found an ally in the Intendant of Franche-Comté, Charles André de la Coré, an enlightened man, he consented to follow this reforming plan.

Even so, it was decided that the social classes would still be segregated thus while the theatre of was the first to have a ground floor amphitheatre furnished with seats for the ordinary paying public.

Thus Ledoux achieved his ambition that the theatre could at the same time be a place of social communion and shared entertainment while still maintaining a strict hierarchy of the classes.

With the aid of the machinist Dart de Bosco [14] Ledoux expanded the wings and back stage scenery apparatus, giving it greater depth than was customary, and many other modern improvements.

Trouble began in 1789 when construction was interrupted by the French Revolution, when only the ground floor walls had been completed [15] Ledoux was a Freemason[16] Ledoux took part, with his friend William Beckford, in various masonic ceremonies at the Loge Féminine de la Candeur which met in the town house he had built for Mme d'Espinchal, on the Rue des Petites-Écuries.

[17] This classical mansion, a venue for Parisian high society, was situated at the heart of a large landscaped garden accessed from the Rue de Provence.

In the process of his work in Franche-Comté, Ledoux had become an architect for the ferme générale, for whom he built a salt storehouse in Compiègne and undertook to plan their vast headquarters on the rue du Bouloi in Paris.

Charles Alexandre de Calonne, the Controller-General of Finances, obtained on an idea from the chemist and fermier général Antoine Lavoisier, of drawing a barrier around Paris to limit contraband and evasion of the octrois, or internal customs duties: this notorious Wall of the Farmers-General was to have six towers (one every 4 kilometers) and to comprise sixty tax-collecting offices.

Ledoux was charged to design these buildings, which he baptized pompously "les Propylées de Paris"[18] and to which he wanted to give a character of solemnity and magnificence while putting into practice his ideas on the necessary links between form and function.

[21] In his Tableau de Paris (1783), Louis-Sébastien Mercier stigmatised "les antres du fisc métamorphosés en palais à colonnes" ("the bastions of taxation metamorphosed into columned palaces"), and exclamed, "Ah!

[22] Ledoux, rendered the object of scandal by these opinions, was relieved of his official functions in 1787 while Jacques Necker, succeeding Calonne, disavowed the entire enterprise.

Perhaps the intervention of the painter Jacques-Louis David, son-in-law of the entrepreneur Pécoul, and considerably enriched in the collection of the octrois, helped him avoid the guillotine.

The differences between a drawing of the Pavillon de Louveciennes as it first was, made by the British architect Sir William Chambers and the engraving that was published in 1804 illustrate this process.

Around the time of the royal saltworks, Ledoux formalized his innovative design ideas for an urbanism and an architecture intended to improve society, of an ideal city charged with symbols and meanings.

[25] As a radical utopian of architecture, teaching at the École des Beaux-Arts, he created a singular architectonic order, a new column formed of alternating cylindrical and cubic stones superimposed for their plastic effect.