Clave (rhythm)

It is present in a variety of genres such as Abakuá music, rumba, conga, son, mambo, salsa, songo, timba and Afro-Cuban jazz.

In considering the clave as this basis of cultural understanding, relation, and exchange, this speaks to the transnational influence and interconnectedness of various communities.

[c] The musical genre known as son probably adopted the clave pattern from rumba when it migrated from eastern Cuba to Havana at the beginning of the 20th century.

An important North American contribution to clave theory is the worldwide propagation of the 3–2/2–3 concept and terminology, which arose from the fusion of Cuban rhythms with jazz in New York City.

Thanks to the popularity of Cuban-based music and the vast amount of educational material available on the subject, many musicians today have a basic understanding of clave.

[failed verification] Chris Washburne considers the term to refer to the rules that govern the rhythms played with the claves.

[26] Godfried Toussaint, a Research Professor of Computer Science, has published a book and several papers on the mathematical analysis of clave and related African bell patterns.

Were the pattern to be suddenly reversed, the rhythm would be destroyed as in a reversing of one magnet within a series... the patterns are held in place according to both the internal relationships between the drums and their relationship with clave... Should the drums fall out of clave (and in contemporary practice they sometimes do) the internal momentum of the rhythm will be dissipated and perhaps even broken—Amira and Cornelius (1992).

The use of the triple-pulse form of the rumba clave in Cuba can be traced back to the iron bell (ekón) part in abakuá music.

The form of rumba known as columbia is culturally and musically connected with abakuá which is an Afro Cuban cabildo that descends from the Kalabari of Cameroon.

The first regular use of the rumba clave in Cuban popular music began with the mozambique, created by Pello el Afrikan in the early 1960s.

[48] John Santos states: "The proper feel of this [rumba clave] rhythm, is closer to triple [pulse].”[49] Conversely, in salsa and Latin jazz, especially as played in North America, 44 is the basic framework and 68 is considered something of a novelty and in some cases, an enigma.

North American musicians often refer to Afro-Cuban 68 rhythm as a feel, a term usually reserved for those aspects of musical nuance not practically suited for analysis.

The ethnomusicologist Arthur Morris Jones correctly identified the importance of this key pattern, but he mistook its accents as indicators of meter rather than the counter-metric phenomena they are.

Because the main beats are usually emphasized in the steps and not the music, it is often difficult for an "outsider" to feel the proper metric structure without seeing the dance component.

Not surprisingly, many misinterpretations of African rhythm and meter stem from a failure to observe the dance.In Cuban popular music, a chord progression can begin on either side of the clave.

The 3–2/2–3 concept and terminology was developed in New York City during the 1940s by Cuban-born Mario Bauza while he was the music director of Machito and his Afro-Cubans.

Working in conjunction with the chord and clave changes, vocalist Frank "Machito" Grillo creates an arc of tension/release spanning more than a dozen measures.

By the time the song changes to 3–2 on the V7 chord, Machito has developed a considerable amount of rhythmic tension by contradicting the underlying meter.

One frequently repeated theory is that the triple-pulse African bell patterns morphed into duple-pulse forms as a result of the influence of European musical sensibilities.

"The duple meter feel [of 44 rumba clave] may have been the result of the influence of marching bands and other Spanish styles..."— Washburne (1995).

Percussion scholar royal hartigan[76] identifies the duple-pulse form of "rumba clave" as a timeline pattern used by the Yoruba and Ibo of Nigeria, West Africa.

He states that this pattern is also found in the high-pitched boat-shaped iron bell known as atoke played in the Akpese music of the Eve people of Ghana.

Soon, they were creating their original Cuban-like compositions, with lyrics sung in French or Lingala, a lingua franca of the western Congo region.

[80] Banning Eyre distills down the Congolese guitar style to this skeletal figure, where clave is sounded by the bass notes (notated with downward stems).

In American pop music, the clave pattern tends to be used as an element of rhythmic color, rather than a guide-pattern and as such is superimposed over many types of rhythms.

Therefore, it is not surprising that we find the bell pattern the Cubans call clave in the Afro-Brazilian music of Macumba and Maculelê (dance).

[85] The examples below are transcriptions of several patterns resembling the Cuban clave that is found in various styles of Brazilian music, on the ago-gô and surdo instruments.

This is suggestive of a pre-determined rhythmic relationship between the vocal part and the percussion and supports the idea of a clave-like structure in Brazilian music.

The son clave rhythm is present in Jamaican mento music, and can be heard on 1950s-era recordings such as "Don’t Fence Her In", "Green Guava" or "Limbo" by Lord Tickler, "Mango Time" by Count Lasher, "Linstead Market/Day O" by The Wigglers, "Bargie" by The Tower Islanders, "Nebuchanezer" by Laurel Aitken and others.

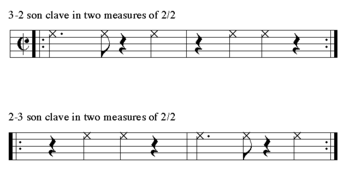

8 clave, the first of which is correct ⓘ