Clerical celibacy in the Catholic Church

According to Jason Berry of The New York Times, "The requirement of celibacy is not dogma; it is an ecclesiastical law that was adopted in the Middle Ages because Rome was worried that clerics' children would inherit church property and create dynasties.

Exceptions are sometimes made, especially in the case of married male Lutheran, Anglican and other Protestant clergy who convert to the Catholic Church,[10] and the discipline could, in theory, be changed for all ordinations to the priesthood.

[19] Paul, within a context of having "no command from the Lord" (1 Corinthians 7:25),[20] recommends celibacy, but acknowledges that it is not God's gift to all within the church: "For I wish that all men were even as I myself.

[30] According to Jason Berry of The New York Times, "The requirement of celibacy is not dogma; it is an ecclesiastical law that was adopted in the Middle Ages because Rome was worried that clerics' children would inherit church property and create dynasties.

[35] This theory would explain why all the ancient Christian Churches of both East and West, with the one exception mentioned, exclude marriage after priestly ordination, and why all reserve the episcopate (seen as a fuller form of priesthood than the presbyterate) for the celibate.

Dennis says "there is simply no clear evidence of a general tradition or practice, much less of an obligation, of priestly celibacy-continence before the beginning of the fourth century.

"[37] The earliest textual evidence of the forbidding of marriage to clerics and the duty of those already married to abstain from sexual contact with their wives is in the fourth-century decrees of the Synod of Elvira and the later Council of Carthage (390).

However, the city of Rome, under the guidance of the Catholic Church, still remained a centre of learning and did much to preserve classical Roman culture in Western Europe.

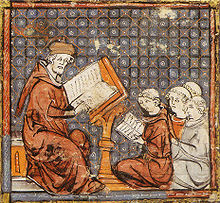

Philosopher Will Durant argues that certain prominent features of Plato's ideal community were discernible in the organization, dogma and effectiveness of the medieval Church in Europe:[42] The clergy, like Plato's guardians, were placed in authority... by their talent as shown in ecclesiastical studies and administration, by their disposition to a life of meditation and simplicity, and ... by the influence of their relatives with the powers of state and church.

In the latter half of the period in which they ruled [800 AD onwards], the clergy were as free from family cares as even Plato could desire [for such guardians].... [Clerical] Celibacy was part of the psychological structure of the power of the clergy; for on the one hand they were unimpeded by the narrowing egoism of the family, and on the other their apparent superiority to the call of the flesh added to the awe in which lay sinners held them....[42]In his book The Ruling Class, Gaetano Mosca wrote of the medieval Church and its structure: [Although] the Catholic Church has always aspired to a preponderant share in political power, it has never been able to monopolize it entirely, because of two traits, chiefly, that are basic in its structure.

[44][45] There is abundant documentation that up to 12th century many priests in Europe were married and that their sons would often follow their path which made the reforms difficult to implement.

[51] The doctrinal view of the Reformers on this point was reflected in the marriages of Zwingli in 1522, Luther in 1525, and Calvin in 1539; in England, the married Thomas Cranmer was made Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533.

Both of these actions, marriage after ordination to the priesthood and consecration of a married man as a bishop, went against the long-standing tradition of the Church in the East as well as in the West.

[57] Garry Wills, in his book Papal Sin: Structures of Deceit, argued that the imposition of celibacy among Catholic priests played a pivotal role in the cultivation of the Church as one of the most influential institutions in the world.

In his discussion concerning the origins of the said policy, Wills mentioned that the Church drew its inspiration from the ascetics, monks who devote themselves to meditation and total abstention from earthly wealth and pleasures in order to sustain their corporal and spiritual purity, after seeing that its initial efforts in propagating the faith were fruitless.

The rationale behind such strict policy is that it significantly helps the priests perform well in their religious services while at the same time following the manner in which Jesus Christ lived his life.

Moreover, the author also mentioned that although the said policy insists on helping priests focus more on ecclesiastical duties, it also enabled the Church to control the wealth amassed by the clerics through their various religious activities, hence contributing to the growing power of the institution.

Fourth, it is said that mandatory celibacy distances priests from this experience of life, compromising their moral authority in the pastoral sphere, although its defenders argue that the Church's moral authority is rather enhanced by a life of total self-giving in imitation of Christ, a practical application of the Vatican II teaching that "man cannot fully find himself except through a sincere gift of himself.

[64] In 2011, hundreds of German, Austrian, and Swiss theologians (249 as of 15 February 2011[65]) signed a letter calling for married priests, as well as for women in Church ministry.

[67] Pope John Paul II wrote in 1992:[68] The synod fathers clearly and forcefully expressed their thought on this matter in an important proposal which deserves to be quoted here in full: "While in no way interfering with the discipline of the Oriental churches, the synod, in the conviction that perfect chastity in priestly celibacy is a charism, reminds priests that celibacy is a priceless gift of God for the Church and has a prophetic value for the world today.

This synod strongly reaffirms what the Latin Church and some Oriental rites require, that is that the priesthood be conferred only on those men who have received from God the gift of the vocation to celibate chastity (without prejudice to the tradition of some Oriental churches and particular cases of married clergy who convert to Catholicism, which are admitted as exceptions in Pope Paul VI's encyclical on priestly celibacy, no.

The synod does not wish to leave any doubts in the mind of anyone regarding the Church's firm will to maintain the law that demands perpetual and freely chosen celibacy for present and future candidates for priestly ordination in the Latin rite.He added that the "unchanging" essence of ordination "configures the priest to Jesus Christ the Head and Spouse of the Church."

"[71] Yet some commentators have argued for the possibility that married men of proven seriousness and maturity (viri probati, taking up a phrase which appears in the first-century First Epistle of Clement in a different context)[72] might be ordained to a localized and modified form of the priesthood.

[73] The topic of viri probati was raised by some participants in discussions at Ordinary General Assembly XI of the Synod of Bishops held at the Vatican in October 2005 on the theme of the Eucharist, but it was rejected as a solution for the insufficiency of priests.

"[76] National Catholic Reporter Vatican analyst, Jesuit Thomas J. Reese, called Bergoglio's use of "conditional language" regarding the rule of celibacy "remarkable.

[101] Noted Indian Physician Dr Edmond Fernandes called celibacy a "historical ill" urging the Catholic Church to immediately withdraw.

[102] Exceptions to the rule of celibacy for priests of the Latin Church are sometimes granted by authority of the Pope, when married Protestant clergy become Catholic.

[4][5][3] It was also revealed that during the course of history, rules were secretly established by the Vatican to protect clergy who had violated the celibacy policy, including those who fathered children.

[9] Regarding violation of the celibacy policy, Stella stated "In such cases there are, unfortunately, Bishops and Superiors who think that, after having provided economically for the children, or after having transferred the priest, the cleric could continue to exercise the ministry.

This ban, which some bishops determined to be null in various circumstances or at times or simply decided not to enforce, was finally rescinded by a decree of June 2014.