Coccolithophore

[1] Coccolithophores are ecologically important, and biogeochemically they play significant roles in the marine biological pump and the carbon cycle.

[3] They are of particular interest to those studying global climate change because, as ocean acidity increases, their coccoliths may become even more important as a carbon sink.

[9][10] and for its production of molecules known as alkenones that are commonly used by earth scientists as a means to estimate past sea surface temperatures.

[6] Coccolithophores are distinguished by special calcium carbonate plates (or scales) of uncertain function called coccoliths, which are also important microfossils.

[14] Coccolithophores are single-celled phytoplankton that produce small calcium carbonate (CaCO3) scales (coccoliths) which cover the cell surface in the form of a spherical coating, called a coccosphere.

[29][27] Viral infection is an important cause of phytoplankton death in the oceans,[30] and it has recently been shown that calcification can influence the interaction between a coccolithophore and its virus.

These are estimated to consume about two-thirds of the primary production in the ocean[33] and microzooplankton can exert a strong grazing pressure on coccolithophore populations.

Two large chloroplasts with brown pigment are located on either side of the cell and surround the nucleus, mitochondria, golgi apparatus, endoplasmic reticulum, and other organelles.

[57] The Great Calcite Belt, defined as an elevated particulate inorganic carbon (PIC) feature occurring alongside seasonally elevated chlorophyll a in austral spring and summer in the Southern Ocean,[58] plays an important role in climate fluctuations,[59][60] accounting for over 60% of the Southern Ocean area (30–60° S).

As they are calcifying organisms, it has been suggested that ocean acidification due to increasing carbon dioxide could severely affect coccolithophores.

The increase in agricultural processes lead to eutrophication of waters and thus, coccolithophore blooms in these high nitrogen and phosphorus, low silicate environments.

[46][69] Viruses specific to this species have been isolated from several locations worldwide and appear to play a major role in spring bloom dynamics.

Some of these toxic species are responsible for large fish kills and can be accumulated in organisms such as shellfish; transferring it through the food chain.

[71] More recent work has suggested that viral synthesis of sphingolipids and induction of programmed cell death provides a more direct link to study a Red Queen-like coevolutionary arms race at least between the coccolithoviruses and diploid organism.

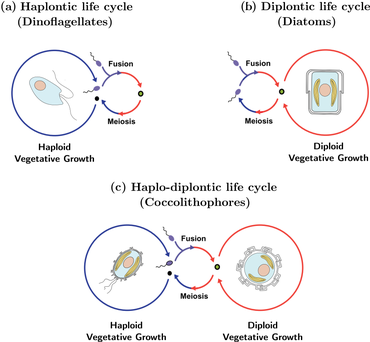

Holococcoliths are produced only in the haploid phase, lack radial symmetry, and are composed of anywhere from hundreds to thousands of similar minute (ca 0.1 μm) rhombic calcite crystals.

[77] More specific, defensive properties of coccoliths may include protection from osmotic changes, chemical or mechanical shock, and short-wavelength light.

[10] At the present day sedimented coccoliths are a major component of the calcareous oozes that cover up to 35% of the ocean floor and is kilometres thick in places.

[50] Because of their abundance and wide geographic ranges, the coccoliths which make up the layers of this ooze and the chalky sediment formed as it is compacted serve as valuable microfossils.

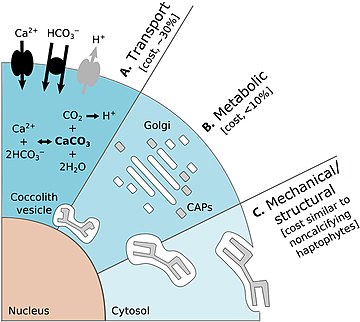

Cell physiological examinations found the essential H+ efflux (stemming from the use of HCO3− for intra-cellular calcification) to become more costly with ongoing ocean acidification as the electrochemical H+ inside-out gradient is reduced and passive proton outflow impeded.

[82] Reduced intra-cellular pH would severely affect the entire cellular machinery and require other processes (e.g. photosynthesis) to co-adapt in order to keep H+ efflux alive.

[85][86] Unraveling these fundamental constraints and the limits of adaptation should be a focus in future coccolithophore studies because knowing them is the key information required to understand to what extent the calcification response to carbonate chemistry perturbations can be compensated by evolution.

On the contrary, dinoflagellates (except for calcifying species;[88] with generally inefficient CO2-fixing RuBisCO enzymes[89] may even profit from chemical changes since photosynthetic carbon fixation as their source of structural elements in the form of cellulose should be facilitated by the ocean acidification-associated CO2 fertilization.

Under these conditions dinoflagellates could down-regulate the energy-consuming operation of carbon concentrating mechanisms to fuel the production of organic source material for their shell.

[95] In 2020, researchers found that in situ ingestion rates of microzooplankton on E. huxleyi did not differ significantly from those on similar sized non-calcifying phytoplankton.

[98] In 2018, Strom et al. compared predation rates of the dinoflagellate Amphidinium longum on calcified relative to naked E. huxleyi prey and found no evidence that the coccosphere prevents ingestion by the grazer.

[103] Research also suggests that ocean acidification due to increasing concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere may affect the calcification machinery of coccolithophores.

This may not only affect immediate events such as increases in population or coccolith production, but also may induce evolutionary adaptation of coccolithophore species over longer periods of time.

When the function of these ion channels is disrupted, the coccolithophores stop the calcification process to avoid acidosis, thus forming a feedback loop.

Groups like the European-based CALMARO[107] are monitoring the responses of coccolithophore populations to varying pH's and working to determine environmentally sound measures of control.

They thrive in warm seas and release dimethyl sulfide (DMS) into the air whose nuclei help to produce thicker clouds to block the sun.