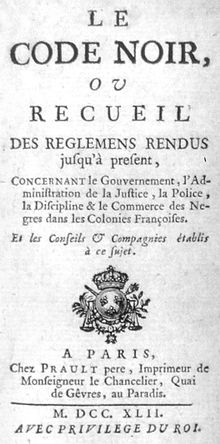

Code Noir

[1][2][3] The code has been described by historian of modern France Tyler Stovall as "one of the most extensive official documents on race, slavery, and freedom ever drawn up in Europe".

Strict religious morals were also imposed in the crafting of the Code noir; in part a result of the influence of the influx of Catholic leaders arriving in the Antilles between 1673 and 1685.

The title Code noir first appeared during the regency of Philippe II, Duke of Orleans, (1715–1723) under minister John Law, and referred to a compilation of two separate ordinances of Louis XIV from March and August 1685.

The Marquis de Seignelay wrote the draft using legal briefs written by the first intendant of the French islands of the Americas, Jean-Baptiste Patoulet [fr], as well as those of his successor Michel Bégon.

[6][8] The later two supplemental texts concerning the Mascarene Islands and Louisiana were drafted during Phillippe II's regency and ratified by King Louis XV (a minor of thirteen) in December 1723 and March 1724 respectively.

According to anthropological historian Claude Massilloux, it is the mode of reproduction that distinguishes slavery from serfdom: while a serf cannot be purchased, they reproduce through demographic growth.

[8] The first article of the Code noir enjoins a Catholic expulsion of all Jews residing in the colonial territories due to their being "sworn enemies of the Christian faith" (ennemis déclarés du nom chrétien), within three months under penalty of the confiscation of person and property.

The Antillean Jews targeted by the Code noir were mainly descendants of families of Portuguese and Spanish origin who had come from the Dutch colony of Pernambuco in Brazil.

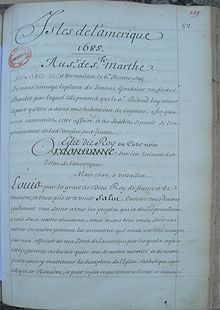

Based on the fundamental law that any man who sets foot on French soil is free, various parliaments refused to pass the original Ordonnance ou édit de mars 1685 sur les esclaves des îles de l'Amérique which was ultimately instituted only in the colonies for which the edict was written: the Sovereign Council of Martinique on 6 August 1685, Guadeloupe on 10 December of the same year, and in Petit-Goâve before the Council of the French colony of Saint-Domingue on 6 May 1687.

[25] The Code Noir was not originally intended for northern New France (present day Canada) which followed the general principle of French law that Indigenous peoples of lands conquered or surrendered to the Crown should be considered free royal subjects (régnicoles) upon their baptism.

However, on 13 April 1709, an ordinance created by Acadian colonial intendant Jacques Raudot imposed regulations on slavery thereby recognizing, de facto, its existence in the territory.

This would only be effective, however, in Saint-Domingue, Guadeloupe, and Guiana, because Martinique was, at this time, a British colony and Mascarene colonists forcibly opposed the institution of the 1794 decree when it finally arrived to the isle in 1796.

Article 8 of the decree of 27 April 1848 extended the Second Republic's ban on slavery to all French citizens residing in foreign countries where the possession of slaves was legal, while according them a grace period of three years to conform to the new law.

The first official French establishment in the Antilles was the Company of Saint Christopher and neighboring islands (Compagnie de Saint-Christophe et îles adjacentes) which was founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1626.

[32] Starting in 1653-1654 the population greatly increased with the arrival of 50 Dutch nationals to the French isles, who had been run out of Brazil, taking with them 1200 black and métis slaves.

[34] Many of these immigrants were Sephardic Jewish planters from Bahia, Dutch Pernambuco, and Suriname, who brought sugarcane infrastructure to French Martinique and English Barbados.

Some historians suggest that these Jewish planters, such as Benjamin da Costa d'Andrade, were responsible for introducing commercial sugar production to the French Antilles.

[38] Thereafter, the French State made the facilitation of the slave trade a matter of primary concern and worked to undercut foreign competition, particularly Dutch slavers.

[42] For this reason, the Code inverted basic patrimonial French custom in maintaining that even if the father is free, the children of an enslaved woman shall be slaves unless they are rendered legitimate through the marriage of the parents, which was a rare occurrence.

The Code Noir was a multifaceted legal document designed to govern every aspect of the lives of enslaved and free African people under French colonial rule.

While Enlightenment thinking about liberty and tolerance prevailed dominantly in French society, it became necessary to clarify that people of African descent did not belong under this umbrella of understanding.

It required that all enslaved people of African descent in the French colonies receive baptism, religious instruction, and the same practices and sacraments for slaves as it did for free persons.

While it did grant enslaved people the right to rest on Sundays and holidays, to formally marry through the church, and to be buried in proper cemeteries, forced religious conversion was just one of the many methods that France used to attempt to 'civilize' and exert their imperial control over the Black population in the French colonies.

Contrary to the thinking of legal theorists such as Leonard Oppenheim,[49] Alan Watson,[50] and Hans W. Baade,[51] it was not slave legislation from Roman law that served as inspiration for the Code Noir, but rather a collection and codification of the local customs, decisions, and regulations used in the Antilles.

According to legal scholar Vernon Palmer, who has described the lengthy four-year decision-making process that led to the original 1685 edict, the project consisted of 52 articles for the first draft and preliminary report, as well as the instructions of the King.

[58] The colonial intendants' work was centered in Martinique, where multiple nobles of the royal entourage had received estates and where Patoulet had requested Louis XIV to ennoble the plantation owners who owned more than one hundred slaves.

[61] According to Sala-Molins, the Code Noir served two purposes: to affirm "the sovereignty of the State in its farthest territories" and to create favorable conditions for the sugarcane commerce.

[65] Denis Diderot, in a passage of Histoire des deux Indes, denounces slavery and imagines a large slave revolt orchestrated by a charismatic leader that leads to a complete reversal of the established order.

The assassin Adéwalé, formerly an escaped slave turned pirate, aids local Maroons in freeing the enslaved population of Saint-Domingue (now the Republic of Haiti).

It is mentioned during the main story of Assassin's Creed IV: Black Flag and has its own database entry in the game, which provides background on the Code Noir.