Coffee roasting

The first recorded implements for roasting coffee beans were thin pans made from metal or porcelain, used in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire and Greater Persia.

The first known implements for roasting coffee beans were thin, circular, often perforated pans made from metal or porcelain, used in the 15th century in the Ottoman Empire and Greater Persia.

This type of shallow, dished pan was equipped with a long handle so that it could be held over a brazier (a container of hot coals) until the coffee was roasted.

It was made of metal, most commonly tinned copper or cast iron, and was held over a brazier or open fire.

[7] As well, the 1864 marketing breakthrough of the Arbuckle Brothers in Philadelphia, introducing the convenient one-pound (0.45 kg) paper bag of roasted coffee, brought success and imitators.

[5] In 1903 and 1906 the first electric roasters were patented in the U.S. and Germany, respectively; these commercial devices eliminated the problem of smoke or fuel vapor imparting a bad taste to the coffee.

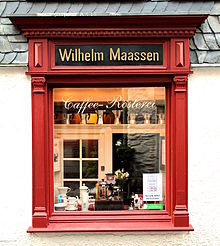

Coffee was roasted to a dark color in small batches at home and by shopkeepers, using a variety of appliances including ones with a rotating cylinder of glass, sheet iron or wire mesh, and ones driven by hand, clockwork or electric motor.

[12] In 1976, chemical engineer Michael Sivetz patented a competing hot air design for manufacture in the U.S.; this became popular as an economical alternative.

By 2001, gourmet coffee aficionados were using the internet to purchase green estate-grown beans for delivery by mail.

Bags of green coffee beans are hand- or machine-opened, dumped into a hopper, and screened to remove debris.

The green beans are then weighed and transferred manually, by belt, or pneumatic conveyor to storage hoppers.

During the roasting process, coffee beans lose 15 to 18% of their mass due mainly to the loss of water but also to volatile compounds.

[19] The most common roasting machines are of two basic types: drum and hot-air, although there are others including packed-bed, tangential and centrifugal roasters.

Any number of factors may help a person determine the best profile to use, such as the coffee's origin, variety, processing method, moisture content, bean density, or desired flavor characteristics.

As the coffee absorbs heat, the color shifts to yellow and then to increasingly darker shades of brown.

The famous Italian roaster Gianni Frasi explains how artisanal roasting is fundamental in order to obtain a high quality coffee ("immersion in direct flame is purification, it makes a dead bean alive", "the bean's dignity can only be guaranteed by an open flame"[26]).

The craft system was codified by Italian author Luca Farinotti[27] in his 2019 award-winning book[28] World and restaurant.

At first crack, a large amount of the coffee's moisture has been evaporated and the beans will begin to increase in size.

This sound represents the structure of the coffee becoming brittle and fracturing as the bean continues to swell and enlarge from internal pressure.

[30] Lipids present inside the coffee seed liquify from heat and pressure built up in the bean.

[29] These images depict samples taken from the same batch of a typical Brazilian green coffee at various bean temperatures with their subjective roast names and descriptions.

The beans can be stored for approximately 12–18 months in a climate controlled environment before quality loss is noticeable.

Medium-dark brown with dry to tiny droplets or faint patches of oil, roast character is prominent.

[32] Moderate dark brown with light surface oil, more bittersweet, caramel flavor, acidity muted.

[34] At lighter roasts, the coffee will exhibit more of its "origin character"—the flavors created by its variety, processing, altitude, soil content, and weather conditions in the location where it was grown.

[44] In some cases there is an economic advantage, but primarily it is a means to achieve finer control over the quality and characteristics of the finished product.

Extending the shelf life of roasted coffee relies on maintaining an optimum environment to protect it from exposure to heat, oxygen, and light.

The roaster is the main source of gaseous pollutants, including alcohols, aldehydes, organic acids, and nitrogen and sulfur compounds.

Decaffeination and instant coffee extraction and drying operations may also be sources of small amounts of VOC.

Particulate matter emissions from the roasting and cooling operations are typically ducted to cyclones before being emitted to the atmosphere.