Cog (ship)

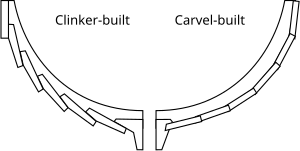

Cogs were a type of round ship,[1] characterized by a flush-laid flat bottom at midships which gradually shifted to overlapped strakes near the posts.

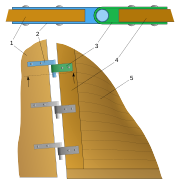

Caulking was generally tarred moss that was inserted into curved grooves, covered with wooden laths, and secured by metal staples called sintels.

[8] The cog-built structure would be completed with a stern-mounted, hanging, central rudder on a heavy stern-post, which was a uniquely northern development.

[14] From the 13th century cogs would be decked and larger vessels would be fitted with a stern castle, to afford more cargo space by keeping the crew and tiller up, out of the way; and to give the helmsman a better view.

[17][18] This made them unhandy, limiting their ability to tack in the harbour and making them very reliant on wind direction at the start of voyages.

[17][19] The flat bottom permitted cogs to be readily beached and unloaded at low tide when quays were not available; a useful trait when purpose-built jetties were not common.

Another development was into Kahnen, flat-bottomed boats, with pointed ends for and aft that were constructed by splitting a hollowed-out log and widening the bottom with planks that were nailed to knee-shaped ribs attached to the sides.

The pointed ends (called Block locally) of the log would be cut off and attached separately to the widened hull which resulted in so-called Blockkahnen, variants of which are still in use.

The earliest evidence of a cog-like craft is a clay model found in Leese on the middle Weser from the grave of an adult male who died around 200 BC.

After Roman power collapsed in the middle of the first millennium AD, transports on the large river estuaries and the sheltered waters of the Wadden Sea was taken over by Frisians who used vessels based on indigenous, flat-bottomed designs that were precursors of later medieval cogs.

The transformation of the cog into a true seagoing trader came not only during the time of the intense trade between West and East but also as a direct answer to the closure of the western entrance to the Limfjord.

Due to its unusual geographical conditions and strong currents, the passage was constantly filling with sand and was completely blocked by the early 12th century.

The larger ships, which could not be pulled across the sand bars, had to sail around the Jutland peninsula and circumnavigate the dangerous Cape Skagen to get to the Baltic.

[23] This resulted in major modifications to old ship structures, which can be observed by analyzing the evolution of the earliest cog finds of Kollerup, Skagen, and Kolding.

[25] The first archaeological find that was identified as a cog, was a ship wreck discovered in 1944 by P. J. R. Modderman in the Noordoostpolder near Emmeloord (plot NM 107).

[27] In 2012, a cog dating from the early 15th century was discovered preserved from the keel up to the decks in the silt of the River IJssel in the city of Kampen, Netherlands.

[28] During its excavation and recovery an intact brick dome oven and glazed tiles were found in the galley as well as a number of other artifacts.