Colfax massacre

After the contested 1872 election for governor of Louisiana and local offices, a group of White men armed with rifles and a small cannon overpowered Black freedmen and state militia occupying the Grant Parish courthouse in Colfax.

After this ruling, the federal government could no longer use the Enforcement Act of 1870 to prosecute actions by paramilitary groups such as the White League, which had chapters forming across Louisiana beginning in 1874.

Intimidation, murders, and Black voter suppression by such paramilitary groups were instrumental to the Democratic Party regaining political control of the state legislature by the late 1870s.

During the late 20th and early 21st centuries, historians have given renewed attention to the events at Colfax and the resulting Supreme Court case.

[7] It was postponed because of the New Orleans massacre that day, in which armed Southern White Democrats attacked Black Americans who had a parade in support of the convention.

Anticipating trouble, the mayor of New Orleans had asked the local military commander to police the city and protect the convention.

President Johnson, a Democrat, prevented the Republican governor of Louisiana from using either the state militia or US forces to suppress the insurgent groups, such as the Knights of the White Camelia.

The ballot box was originally at a store owned by John Hooe,[16] who had threatened to whip freedmen "if they voted Republican".

[19] A group of Whites threw the ballot box into the Red River, and Democrats arrested Calhoun, alleging election fraud.

According to Lane, after Ulysses S. Grant became President in 1869, he "lobbied hard for the Fifteenth Amendment" (ratified February 3, 1870),[22] which guaranteed that Black men, most of whom were newly freed slaves, would have the right to vote.

[23] However, the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) continued violent attacks and killed scores of Black residents in Arkansas, South Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi and elsewhere.

[24] In response, on May 31, 1870, Congress passed an Enforcement Act which prohibited groups of people from banding together to violate citizens' constitutional rights.

Ward, born a slave in 1840 in Charleston, South Carolina, had learned to read and write as a valet to a master in Richmond, Virginia.

This action was widely criticized across the nation by Democrats and both factions of the Republican Party because it was considered to be a violation of the rights of states to manage their own (non-federal-office) elections.

Warmoth appointed Democrats as parish registrars, and they ensured the voter rolls included as many Whites and as few freedmen as possible.

In Grant Parish, one plantation owner threatened to expel Black people from homes they rented on his land if they voted Republican.

Warmoth issued commissions to Fusionist Democrats Alphonse Cazabat and Christopher Columbus Nash, elected parish judge and sheriff, respectively.

Like many White men in the South, Nash was a Confederate veteran (as an officer, he had been held for a year and a half as a prisoner of war at Johnson's Island in Ohio).

[32] Fearful that the Democrats might try to control the local parish government, Black people started to create trenches around the courthouse and drilled to keep alert.

[36] He wrote to Governor Kellogg seeking US troops for reinforcement and gave the letter to William Smith Calhoun for delivery.

[37] On April 8 the anti-Republican Daily Picayune newspaper of New Orleans inflamed tensions and distorted events by the following headline: THE RIOT IN GRANT PARISH.

"[39] Suffering from tuberculosis and rheumatism, on April 11 the militia captain Ward took a steamboat downriver to New Orleans to seek armed help directly from Kellogg.

Nash gathered an armed White paramilitary group and veteran officers from Rapides, Winn and Catahoula parishes.

[43] Kellogg sent state militia colonels Theodore DeKlyne and William Wright to Colfax with warrants to arrest 50 White men and to install a new, compromise slate of parish officers.

DeKlyne and Wright found the smoking ruins of the courthouse at Colfax, and many bodies of men who had been shot in the back of the head or the neck.

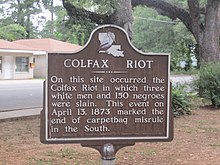

[45] The exact number of dead was never established: two US Marshals, who visited the site on April 15 and buried dead, reported 62 fatalities;[46] a military report to Congress in 1875 identified 81 Black men by name who had been killed, and also estimated that between 15 and 20 bodies had been thrown into the Red River, and another 18 were secretly buried, for a grand total of "at least 105";[47] a state historical marker from 1950 noted fatalities as three Whites and 150 Blacks.

It had been designed to provide federal protection for civil rights of freedmen by the Fourteenth Amendment against actions by terrorist groups such as the Klan.

[52] The publicity about the Colfax massacre and subsequent Supreme Court ruling encouraged the growth of White paramilitary organizations.

[54] Such violence served to intimidate voters and officeholders; it was one of the methods that White Democrats used to gain control of the state legislature in the 1876 elections and ultimately to end Reconstruction in Louisiana.

[63] In his book, Lane addressed the political and legal implications of the Supreme Court case, which were derived from the prosecution of several men who were member of the White paramilitary groups.