Colin Blythe

[d][9] The growing size of his family probably prompted him to leave school at the earliest age possible and he became an apprentice engineer fitter and turner alongside his father at the Woolwich Arsenal.

There is no evidence that he watched cricket until Saturday 17 July 1897 when Blythe, then aged 18, attended the third and final day of a county match between Kent and Somerset at Rectory Field, Blackheath, a ground relatively close to his home.

[10][15][16] When he arrived there were very few spectators—Blythe recalled that "I don't think there were that many more spectators than players"—and one of the Kent team, Walter Wright, came to bat in the nets and asked Blythe, as one of the few present, to bowl to him to give him some practice before play began.

[6][25][26] The Tonbridge nursery ... has just now given Kent a bowler of great promise in Blythe, a left-hand man of about the pace of Rhodes of Yorkshire, with a fine easy action.

The players also gained match practice by playing for local clubs which were able to request their service, and Blythe quickly developed the key cricketing skills, such as line-and-length bowling and variations in the flight and spin of the ball, he would use with great success throughout his career.

[43][44] Although it is uncertain what the nature of the illness was, one of his biographers, Christopher Scoble, speculates that it may have been related to his later epilepsy, or that he was affected by the attention brought about by his successful first full season.

[46][47][48] When conditions favoured his bowling, however, he had success, for example taking seven for 64 against Surrey, and even on good batting pitches Blythe made it difficult for batsmen to score quickly and generally conceded few runs.

[46] The good impression that Blythe had made during his first two seasons led to his selection for an English team to tour Australia organised by Archie MacLaren.

[i] Two of the leading English professional bowlers, Wilfred Rhodes and George Hirst, were refused permission to join the tour by their county, Yorkshire, so MacLaren chose Blythe and several other promising cricketers.

Scoble suggests that he enjoyed the tour and "took part fully in the social aspects",[54] including playing his violin with the ship's band during the voyage to Australia.

[73] The domestic season was followed by Kent's short tour of the United States, Blythe taking ten wickets in the two first-class matches played in America.

He showed again that he could perform on harder pitches and slow the run-scoring of batsmen when necessary, bowling for an hour against Sussex at Tunbridge Wells in a high-scoring match without conceding a run.

[79] At the end of the season he was the subject of one of the prestigious front-page profiles in Cricket magazine,[80][81] and The Times wrote that Blythe had "strong claims to be considered the best left-hander of his pace".

[l] The English team was not particularly strong and featured only three players, including Blythe, who had played against Australia the previous season,[93][94] although Wisden was of the view it was "good enough" for the task, albeit short of a fast bowler.

[96] In South Africa, Blythe was successful, taking over 100 wickets in all games, including 57 in first-class matches, and thrived on the matting pitches used at the time in the country.

[115] Scoble observes that Blythe's problems with nervous exhaustion and epilepsy became more noticeable in the cricket season immediately following his marriage, and speculates that the root cause may have been from his changed domestic circumstances.

[124] The feat was praised in the contemporary press, and mystique built up around it in later years—possibly owing to Blythe's early death, or the nostalgia which surrounds this era of cricket—including stories that only his dropped catch prevented him taking all twenty wickets in the game.

[125] Blythe missed the next two games with a chill; this may have been caused by playing in wet conditions, but Scoble suggests it may have been exacerbated by the mental strain of his bowling performance.

Wisden judged: "Blythe was so far below his form at home that he was left out of four of the Test games... [He] headed the bowling averages but, though successful against weak teams, he did not trouble the good batsmen.

"[132] Awarded £200 for his efforts on the tour, it is likely that Blythe was unhappy when Kent asked him and his county team-mate in the MCC party, Arthur Fielder, to give the money to them for investment.

[138] His benefit eventually yielded £1,519, a considerable amount for the period and well above average; following their usual practice, the Kent Committee invested the money on Blythe's behalf.

[141] At the start of his next game, for Kent, Blythe was overcome with emotion when the crowd gave him an ovation for his performance in the Test; when he later came on to bowl, he complained of feeling faint after his first over.

"[146] To justify themselves, the selectors made public the medical report on Blythe, which stated that he suffered from strain of the nervous system brought about from playing in Test matches.

[156] After the start of World War I in early August 1914, cricket continued to be played, although public interest declined and the social side of the game was curtailed.

Dover week was moved to Canterbury as The Crabble was being converted to a military camp, and in his final game on the ground Blythe took eleven wickets against Worcestershire, including seven for 20 on a drying pitch to win the match for Kent.

[172] After spending the first years of the war working on coastal defences and other construction projects around Kent, the introduction of conscription in January 1916 meant that territorials were required to sign Imperial Service Obligations and were liable to be sent overseas.

[177][184] Working in the Ypres Salient sector of the front, the battalion was mainly engaged in laying and maintaining light railway lines to allow easy passage of men, equipment and munitions across the area during the Battle of Passchendaele.

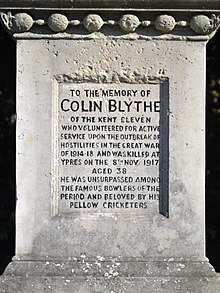

[189][190][191] Inscribed in block letters on the west face of the plinth was the dedication: "To the memory of Colin Blythe of the Kent Eleven who volunteered for active service upon the outbreak of hostilities in the Great War of 1914–18 and was killed at Ypres on the 18th Nov 1917.

Pelham Warner, who had played with Blythe for England and was a great admirer of his, laid a wreath at the memorial during the 1919 Canterbury Cricket Week, beginning a tradition which has continued.

[21][163] Off the field, Blythe played the violin and Harry Altham, writing in Barclay's World of Cricket, said that his slow left-arm action "reflected the sensitive touch and the sense of rhythm of a musician", the left arm emerging from behind his back "in a long and graceful arc".