Colonial Defence Committee

One of the CDC's first actions was to ask the colonial governments to report on the condition of defences, the number of troops and quantity of stores held.

In some cases, as in Saint Helena, where local means were not sufficient the committee drew up plans for defences which were funded by the British government.

The CDC continued the policy that land-based defence was the responsibility of the colonial governments, assisted by the maritime supremacy of the Royal Navy.

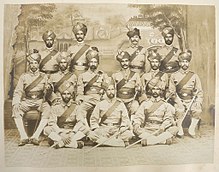

Colonial governments were expected to make their own arrangements to raise forces to carry out internal policing and border defence duties.

The commission found many colonial governments were unable to answer their queries, requiring investigation by Royal Navy officers.

The Governor of British Ceylon, James Robert Longden, had ordered the movement of 50,000 long tons (51,000 t) of coal and transported the colony's treasury inland.

[9] Canada was among the slowest to prepare its plan, to the worry of the CDC particularly after the Venezuelan crisis of 1895, and began work only after the intervention of Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain.

[11] Between 1895 and 1905 the CDC itself drew up plans for the defence of Jamestown, Saint Helena, which they considered vulnerable to attack from an organised expedition and whose loss would threaten trade in the South Atlantic.

This would provide a pool of colonial troops, perhaps up to 10,000 each from Canada, Australia and South Africa, who could be called upon to serve alongside the British Army at short notice.

These plans were resisted by some colonial governments, including Canada and Australia where there were significant factions opposed to involvement in foreign wars.

However, with the government focussed on reform of the imperial troops under Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher's War Office Reconstitution Committee, the Royal Commission on the South African War and the Royal Commission on Militia and Volunteers; together with the 1904 establishment of the Committee of Imperial Defence (CID) left the CDC sidelined.

[17] In a similar case the CDC and the CID could not persuade the British government that Australia, which contributed a subsidy towards Royal Navy vessels, should not be allowed any control over the deployment of the naval force.

[18] The CDC was essentially a committee of military experts, while the CID had more senior personnel and included political figures.

In common with British cabinet practice of the 19th century no minutes or agendas of meetings of the CDC were kept, though its memoranda survive.

[21] In 1909 one of the recommendations of the CDC came to fruition when a meeting with Dominion governments saw an agreement reached for their armed forces to receive standardised War Office training with a view towards becoming a "homogenous Imperial Army".