British Hong Kong

From 1841 to 1997, except for a brief period of Japanese occupation during World War II between 1941 and 1945, Hong Kong was a British crown colony and, from 1981 until its handover, a dependent territory of the United Kingdom.

[6][7] In 1836, the imperial government of the Qing dynasty undertook a major policy review of the opium trade, which had been first introduced to the Chinese by Persian then Islamic traders over many centuries.

Chief Superintendent of Trade, Charles Elliot, complied with Lin's demands to secure a safe exit for the British, with the costs involved to be resolved between the two governments.

[13] He viewed the sudden strict enforcement as laying a trap for the foreign traders, and the confinement of the British with supplies cut off was tantamount to starving them into submission or death.

[14] Palmerston demanded a territorial base in the Chusan Islands for trade so that British merchants "may not be subject to the arbitrary caprice either of the Government of Peking, or its local Authorities at the Sea-Ports of the Empire".

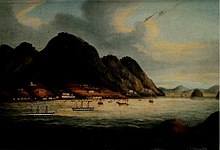

On 20 January, Elliot announced "the conclusion of preliminary arrangements", which included the cession of the barren Hong Kong Island and its harbour to the British Crown.

[19] Hong Kong Island was ceded in the Treaty of Nanking on 29 August 1842 and established as a Crown colony after the ratification exchanged between the Daoguang Emperor and Queen Victoria was completed on 26 June 1843.

[21]: 5 The Treaty of Nanking failed to satisfy British expectations of a major expansion of trade and profit, which led to increasing pressure for a revision of the terms.

[22] In October 1856, Chinese authorities in Canton detained the Arrow, a Chinese-owned ship registered in Hong Kong to enjoy the protection of the British flag.

In the Treaty of Tientsin, the Chinese accepted British demands to open more ports, navigate the Yangtze River, legalise the opium trade and have diplomatic representation in Beijing.

After negotiations began in April 1898, with the British Minister in Beijing, Sir Claude MacDonald, representing Britain, and diplomat Li Hongzhang leading the Chinese, the Second Convention of Peking was signed on 9 June.

[30] The Japanese imprisoned the ruling British colonial elite and sought to win over the local merchant gentry by appointments to advisory councils and neighbourhood watch groups.

With the surrender of Japan, the transition back to British rule was smooth, for on the mainland the Nationalist and Communist forces were preparing for a civil war and ignored Hong Kong.

In the long run the occupation strengthened the pre-war social and economic order among the Chinese business community by eliminating some conflicts of interests and reducing the prestige and power of the British.

[37][38][39] The British claimed that increasing policing to control movement from Hong Kong to China was impractical, and that the mutual open border policy was responsible.

[42] The lax persecution of the riots Rightists instigators was used by the PRC to criticize the "airy use of the rule of law as a pragmatic stand-in for human rights" that characterized British colonialism.

[43] By this time, Britain no longer considered a Taiwanese conquest of China to be realistic;[44] the evolving discourse on human rights also made it difficult to legitimize being a sponsor of state terrorism.

Further appeals from the Supreme Court were heard by the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, which exercised final adjudication over the entire British Empire.

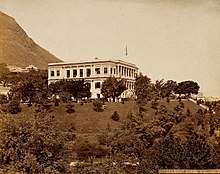

[50] In 1861, Governor Sir Hercules Robinson introduced the Hong Kong Cadetship, which recruited young graduates from Britain to learn Cantonese and written Chinese for two years, before deploying them on a fast track to the Civil Service.

[52] Although the largest businesses in the early colony were operated by British, American, and other expatriates, Chinese workers provided the bulk of the manpower to build a new port city.

[55][56] Most migrants of that era fled poverty and war, reflected in the prevailing attitude toward wealth; Hongkongers tended to link self-image and decision-making to material benefits.

[61] In British-ruled Hong Kong, polygamy was legal until 1971 pursuant to the colonial practice of not interfering in local customs that British authorities viewed as relatively harmless to the public order.

[62] Spiritual concepts such as feng shui were observed; large-scale construction projects often hired consultants to ensure proper building positioning and layout.

Food in Hong Kong under British rule was primarily based on Cantonese cuisine, despite the territory's exposure to foreign influences and its residents' varied origins.

Common cha chaan teng menu items include macaroni in soup, deep-fried French toast, and Hong Kong-style milk tea.

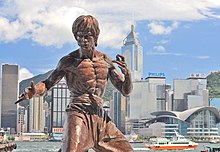

[73] Hong Kong cinema continued to be internationally successful over the following decade with critically acclaimed dramas such as Farewell My Concubine, To Live and Wong Kar Wai movies.

Jackie Chan, Donnie Yen, Jet Li, Chow Yun-fat, and Michelle Yeoh frequently play action-oriented roles in foreign films.

[75] Local media featured songs by artists such as Sam Hui, Anita Mui, Leslie Cheung, and Alan Tam; during the 1980s, exported films and shows exposed Cantopop to a global audience.

[87] During China's turbulent 20th century, Hong Kong served as a safe haven for dissidents, political refugees, and officials who lost power.

[89] Although the 1967 riots started as a labour dispute, the incident escalated quickly after the leftist camp and mainland officials stationed in Hong Kong seized the opportunity to mobilise their followers to protest against the colonial government.