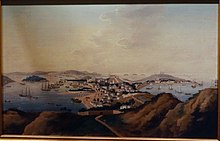

Portuguese Macau

Over time, issues emerged whose resolution could not wait for the Captain-Major's return from his trips to Japan, so a kind of triumvirate was formed, which began to direct the administration of the establishment.

In 1573 or 1574, the Chinese authorities ordered the construction of a barrier on the northern border of the Peninsula, in a place very close to the present-day Portas do Cerco, to prevent the expansion of the Portuguese through the island of Xiangshan (modern Zhongshan), to supervise better the collection of taxes on goods entering or leaving the city, and to control Macau's supply.

In addition to evangelization, these missionaries, especially the Jesuits, also promoted ethical, cultural, and scientific exchange between the West and the East; and contributed in an important way to the development of Macao.

[citation needed] On several occasions, the Jesuits who regularly attended the court in Beijing used their influence to save Macau from various dangers and from various exaggerated demands imposed by the Chinese authorities in Guangzhou or by the Emperor himself.

In another example, some Spaniards even wanted the King of Spain (and Portugal) to order the destruction of Macau, transferring the silver and silk trade between Japan and China to Manila; this proposal was not put into practice.

In 1603, warships from Holland bombarded the city; and in the years 1604 and 1607 came, respectively, the expeditions led by Admirals Wybrand van Warwijck and Cornelis Matelieff de Jonge.

In 1638–1639, the shogun Tokugawa Iemitsu implemented Japan's exclusionary policies, intended to protect it from possible European occupation, and ruthlessly ordered the persecution of all missionaries and priests, and of hundreds of thousands of Japanese Christians.

With the Portuguese expelled, a small number of Dutch, who gained the trust of the Japanese authorities, were able to visit the port of Dejima, although with many restrictions, becoming the only Europeans who were allowed to trade with Japan.

The loss of this important city and commercial base caused disturbances and deviations from the usual route between Macau and Goa and a decrease in the supply of tradable products with China.

In addition to living in uncertainty and fear of being destroyed or occupied by the forces of the new imperial dynasty, the city was also flooded in the 1640s with refugees fleeing the Qings, depleting Macao's resources and giving rise to famine in the 1640s, also due to the dwindling and unstable food supply from Chinese merchants.

These Macau-based traders invested, in addition to Goa and China, in several Asian regional markets, such as Macassar, Solor, Flores, Timor, Vietnam, Siam, Bengal, Calcutta, Banjarmasin, and Batavia.

This emerging class specifically included Chinese buyers and the main shipowners and trade captains who accepted the high risk of sailing in the eastern seas and who knew how to adapt to the new realities of the region.

The Chinese authorities even ordered, in 1648, the establishment of a military post with 500 soldiers in the village of Qianshan (which the Portuguese called Casa Branca), very close to Portas do Cerco, to guard the "City of the Holy Name of God of Macau".

The city prospered with this status and this is also reflected in its urban landscape: new and sometimes exquisite buildings, built according to European-inspired architectural styles, began to appear in Macau, namely in Praia Grande.

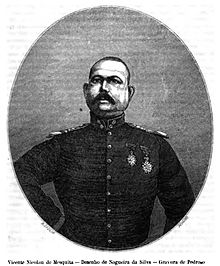

In 1871, the Government of Macau inaugurated the Arco das Portas do Cerco, with the aim of honoring the deeds of Governor Ferreira do Amaral and Colonel Mesquita.

During the second half of the 19th century, the main European powers humiliated the already weak Imperial Chinese Government of the Qing Dynasty, forcing it to sign the so-called Unequal Treaties.

Perhaps taking advantage of the situation, on August 13, 1862, Governor Isidoro Francisco Guimarães managed to get the Chinese government to sign a treaty in Tianjin (or Tientsin).

With this legalization of gambling, which already existed clandestinely in the city, the government wanted to transform the colony into a holiday, leisure and entertainment center for the inhabitants and wealthy merchants of the region.

The coolie trade, which began in Macau in the late 1840s, consisted of supplying contract Chinese workers to countries that at that time needed labor, such as Cuba and Peru.

This trade, while providing new prosperity to the port of Macau, brought serious social problems to the City, such as corruption, moral depression, and the need to deal with a large number of coolies repatriated or waiting to be transported to their new place of work.

[25] Mainly after the end of the tea and coolies trade, still in the 19th century, Macau's economy came to be supported largely by the gambling sector, fishing, and the various monopolies granted by the government (namely that of opium).

[26] The city has always been home to a class of buyers and traders, mostly Chinese, who maintained commercial relations with various locations in China and Southeast Asia, and who made a profit from their intermediary activity of importing products and then re-exporting them.

In the 19th century, the Portuguese also began to expand their influence to the islands of Lapa, Dom João and Montanha (adjacent to Macau), offering protection and services (e.g. education) to the few Chinese residents there in exchange for taxes.

In 1941, during World War II, the Portuguese were expelled and the islands occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army (no armed struggle or deaths were recorded, which constantly launched threats to the government of Macau.

On 26 March 1887, the Lisbon Protocol was signed, in which China recognised the "perpetual occupation and government of Macao" by Portugal who in turn, agreed never to surrender Macau to a third party without Chinese agreement.

The actions of Governor Gabriel Maurício Teixeira and Pedro José Lobo, at the time head or director of the Central Office of Economic Services, were crucial for Macau remaining relatively intact during the war.

Despite Macau's neutrality, a seaplane port was bombed, allegedly by accident, and the islands of Lapa, Dom João and Montanha were occupied by the Japanese Army.

In 1945, after the end of extraterritorial rights in China, the Nationalists called for the liquidation of foreign control over Hong Kong and Macau, but they were too preoccupied in the civil war with the Communists to fulfil their goals.

[28] Portugal offered to withdraw from Macau in late 1974, but China declined in favour of a later time because it sought to preserve international and local confidence in Hong Kong, which was still under British rule.

The transfer of full sovereignty to the People's Republic of China was performed in a ceremony on 20 December 1999, in the early hours of the morning, according to the Joint Declaration, after many years of negotiations and preparations.