Colonial architecture of Brazil

The architect brought in by Tomé de Sousa, Luís Dias, then designs the capital of the colony, including the governor's palace, churches and the first streets, squares and houses, in addition to the indispensable fortification around the settlement.

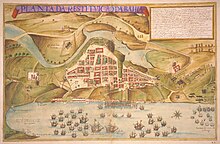

Although they did not follow the rigid checkerboard pattern of Spanish foundations in the New World, many colonial cities, starting with Olinda and Salvador, are now considered to have had their streets laid out with relative regularity.

[5] Also noteworthy are the great urbanistic works carried out in Recife during the government of Count John Maurice of Nassau (1637–1643), who, with the embankment and construction of bridges, canals, and forts, transformed the old port of Olinda into a city.

Moreover, in some places common facade patterns for buildings were adopted with the aim of creating a harmonious urban ensemble, as observed in the lower city of Salvador in the mid-eighteenth century.

José Fernandes Pinto Alpoim, for example, designed in Rio de Janeiro the Imperial Palace, the Convent of Santa Teresa, urbanized the Paço Square and finished the work of the Carioca Aqueduct.

[16] As coastal cities and of greatest importance for the colony, Rio de Janeiro, Salvador and Recife enjoyed this luxury, while in more inland regions it was necessary to exploit the raw material of local abundance, so that sandstone is widely seen applied in masonry with clay mortar, not only in public or religious buildings, but also in housing.

[16] In the early days, the roofs of the houses were simply made with straw (sapé), like the indigenous huts (ocas) or certain African-influenced dwellings, still existing today in rural areas.

This aesthetic is characterized by facades composed of basic geometric figures, triangular pediments, windows close to the square, and walls marked by the contrast between stone and white surfaces, with a two-dimensional aspect.

The facade is composed of geometric shapes, with a triangular pediment, flanked by two towers and with a galley with three portals, similar to the Monastery of São Vicente de Fora in Lisbon.

The interiors of colonial churches should be seen not only in architectural but also decorative terms, as the internal environments were often defined by the harmonious interplay of gilded woodcarving, painting, and azulejos, typical of Portuguese art.

An important example is the Mannerist church of the São Bento Monastery in Rio de Janeiro, whose interior was completely covered with Baroque carving from the last decades of the 17th century.

[31] In Belém, the Pombaline influence is revealed in the work of the Italian architect Giuseppe Antonio Landi, for example in the churches of São João and of Santana, in the capital of Pará.

In Recife there is an important set of facades of Rococo influence, such as the Nossa Senhora do Carmo Basilica and Convent, begun in 1767, the Santo Antônio Mother Church and others, all with curved cornices and exuberant pediments.

In addition, the availability of soapstone (steatite), an easy material to carve, allowed the development of beautiful and original portals by the greatest colonial sculptor, Antônio Francisco Lisboa, Aleijadinho.

On the doorway, the sculptor positioned three tablets with the Wounds of Christ, the Arms of Portugal and, on the upper level, the figure of the Virgin Mary, all intertwined with Franciscan motifs, heads of angels, asymmetric scrolls and ribbons with inscriptions.

In this drawing, one can see how the artist created a facade with strong Rococo characteristics, slightly sinuous like the Carmo Church in Ouro Preto, with a pediment delimited by immense rocalhas and with a high relief of St. Francis kneeling in the center.

[41] Later a series of other forts were erected all along the coast, and at some points in the countryside, and they basically followed the same model that remained without much variation over the centuries, of square or polygonal plan, sometimes deformed to fit the underlying topography.

They had a chamfered base in bare stone, whitewashed masonry walls on top, with guardhouses interspersed, and a series of stripped dwellings inside, often with some chapel or small temple.

A unique case in a different genre is the Carioca Aqueduct, a large civil work for conducting water, erected between the 17th and 18th centuries, located in Rio de Janeiro, 270 m long and 17 m high.

One of the most significant is the former City Council and Jail House in Ouro Preto, today the Inconfidência Museum, with a rich façade where there is a portico with columns, an access staircase, a tower, ornamental statues and a stonework structure.

One of the most compelling and unpassionate accounts of the civil architecture of colonial Brazil is that of the English writer Maria Graham, who was in the three main Brazilian economic centers at the time (Recife, Salvador and Rio de Janeiro).

(...) There can be nothing more beautiful in the genre than the vivid green panorama, with the wide river winding through it, and which can be seen on either side of the bridge, and the white buildings of the Treasury and Mint, the convents and private houses, most of which have their gardens.

"[55] And finally, about Rio de Janeiro, which was experiencing the transformations resulting from the transfer of the Portuguese court to Brazil, she said: "I spent the day paying and receiving visits in the neighborhood.

The streets are narrow, barely wider than the Corso in Rome, with which one or two bear an air of resemblance, especially on feast days, when the windows and balconies are decorated with red, yellow or green damask bedspreads.

In Recife, the Corpo Santo Church, which had its origins in the early days of the settlement, was enlarged in the 18th century gaining a beautiful Lioz stone faCade in the neoclassical style.

In Belém do Pará, Antônio José Landi also designed buildings of marked classical character, such as the Santana Church (1760–1782), the São João Batista Chapel (1769–1772) and the Grão-Pará General Governors' Palace (1768–1772), among others.

In Salvador, engineer Cosme Damião da Cunha Fidié designed in 1813 the city's Comércio Square, a building strongly inspired by the English neo-Palladian style, with Luso-Brazilian touches.

[57] The architect coming with the Mission, Grandjean de Montigny, became Professor of Architecture at the Royal School of Sciences, Arts and Crafts, founded by King John IV in 1816.

The Portuguese furniture developed in Brazil was simple and unpretentious, that is, only the essentials to perform the function of the object (as examples: small oratories, beds, chairs, tables and arks).

But, even though these pieces of furniture were simple and unpretentious, they were well crafted, not only because the tradition of the trade was to develop them in this capricious way, but also because the carpentry officers and helpers were often from the house itself (some being slaves whose skills were discovered), who worked without haste and who did not aim for profit, only "the pleasure of doing it well".