Columbus's letter on the first voyage

The letter provides very few details of the oceanic voyage itself, and covers up the loss of the flagship of his fleet, the Santa María, by suggesting Columbus left it behind with some colonists, in a fort he erected at La Navidad in Hispaniola.

[3] The two earliest published copies of Columbus's letter on the first voyage aboard the Niña were donated in 2017 by the Jay I. Kislak Foundation to the University of Miami library in Coral Gables, Florida, where they are housed.

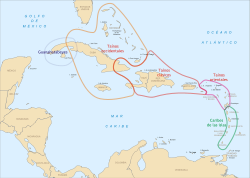

[4] Christopher Columbus, a Genoese captain in the service of the Crown of Castile, set out on his first voyage in August 1492 with the objective of reaching the East Indies by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean.

[11] In the letter, Christopher Columbus does not describe the journey itself, saying only that he traveled thirty-three days and arrived at the islands of "the Indies" (las Indias), "all of which I took possession for our Highnesses, with proclaiming heralds and flying royal standards, and no one objecting".

In his letter, Columbus describes how he sailed along the northern coast of Juana (Cuba) for a spell, searching for cities and rulers, but found only small villages "without any sort of government" ("no cosa de regimiento").

He describes how they go about largely naked, that they lack iron and weapons, and are by nature fearful and timid ("son asi temerosos sin remedio"), even "excessively cowardly" ("en demasiado grado cobardes").

According to Columbus, when persuaded to interact, the natives are quite generous and naïve, willing to exchange significant amounts of valuable gold and cotton for useless glass trinkets, broken crockery, and even shoelace tips ("cabos de agugetas").

In the printed editions (albeit not in the Copiador version) Columbus notes that he tried to prevent his own sailors from exploiting the Indians' naïveté, and that he even gave away things of value, like cloth, to the natives as gifts, in order to make them well-disposed "so that they might be made Christians and incline full of love and service towards Our Highnesses and all the Castilian nation".

Columbus notes that the natives of different islands seem to all speak the same language (the Arawaks of the region all spoke Taíno), which he conjectures will facilitate "conversion to the holy religion of Christ, to which in truth, as far as I can perceive, they are very ready and favorably inclined".

Columbus rounds off with a more optimistic report, saying the local Indians of Hispaniola also told him about a very large island nearby which "abounds in countless gold" ("en esta ay oro sin cuenta").

[19] The Copiador version also mentions other points of personal friction not contained in the printed editions, e.g. references to the ridicule Columbus suffered in the Spanish court prior to his departure, his bowing to pressure to use large ships for ocean navigation, rather than the small caravels he preferred, which would have been more convenient for exploring.

Columbus ends the letter urging their Majesties, the Church, and the people of Spain to give thanks to God for allowing him to find so many souls, hitherto lost, ready for conversion to Christianity and eternal salvation.

According to the Capitulations of Santa Fe negotiated prior to his departure (April 1492), Christopher Columbus was not entitled to use the title of "Admiral of the Ocean Sea" unless his voyage was successful.

[21] In the Copiador version there are passages (omitted from the printed editions) petitioning the monarchs for the honors promised him at Santa Fe, and additionally asking for a cardinalate for his son and the appointment of his friend, Pedro de Villacorta, as paymaster of the Indies.

Finally, his emphatic statement that he formally "took possession" of the islands for the Catholic monarchs, and left men (and a ship) at La Navidad, may have been emphasized to forestall any Portuguese claim.

For much of the past century, many historians have interpreted these notes to indicate that the Latin edition was a translated copy of the letter Columbus sent to the Catholic monarchs, who were holding court in Barcelona at the time.

The story commonly related is that after Columbus's original Spanish letter was read out loud at court, the notary Leander de Cosco was commissioned by Ferdinand II (or his treasurer, Gabriel Sanchez) to translate it into Latin.

While in Rome, Bishop Leonardus arranged for the publication of the letter by the Roman printer Stephanus Plannck, possibly with an eye to help popularize and advance the Spanish case.

[42] The letter's subsequent reprinting in Basel, Paris and Antwerp within a few months, seems to suggest that copies of the Roman edition went along the usual trade routes into Central Europe, probably carried by merchants interested in this news.

[53] Ferdinand II dispatched his own emissary, Lope de Herrera, to Lisbon to request the Portuguese to immediately suspend any expeditions to the west Indies until the determination of the location of those islands was settled (and if polite words failed, to threaten).

Pope Alexander VI (an Aragonese national and friend of Ferdinand II) was brought into the fray to settle the rights to the islands and determine the limits of the competing claims.

[54] (Note: although most of the negotiations were masterminded by Ferdinand II, who took a personal interest in the second voyage, the actual official claim of title on the islands belonged to his wife, Queen Isabella I.

The rights, treaties and bulls pertain only to the Crown of Castile and Castilian subjects, and not to the Crown of Aragon or Aragonese subjects) It was apparently soon realized that the islands probably lay below the latitude boundary, as only a little while later, Pope Alexander VI issued a second bull Eximiae devotionis (officially dated also May 3, but written c. July 1493), that tried to fix this problem by stealthily suggesting the Portuguese treaty applied to "Africa", and conspicuously omitting mention of the Indies.

The Portuguese envoys Pero Diaz and Ruy de Pina arrived in Barcelona in August, and requested that all expeditions be suspended until the geographical location of the islands was determined.

As the king wrote Columbus (September 5, 1493), the Portuguese envoys had no clue where the islands were actually located ("no vienen informados de lo que es nuestro"[57]).

Neither of these editions are mentioned by any writers before the 19th century, nor have any other copies been found, which suggests they were very small printings, and that the publication of Columbus's letter may have been suppressed in Spain by royal command.

[68] It is likely that Andrés Bernáldez, chaplain of Seville, may have had or seen a copy (manuscript or printed) of the Spanish letter to Santangel, and paraphrased it in his own Historia de los Reyes Católicos (written at the end of the 15th century).

The Barcelona edition is replete with small errors (e.g., "veinte" instead of "xxxiii" days) and Catalan-style spellings (which Columbus would not have used), suggesting it was carelessly copied and hurriedly printed.

The manuscript was subsequently carried (or received) by the Neapolitan prelate Leonardus de Corbaria, Bishop of Monte Peloso, who took it to Rome and arranged for its printing there with Stephanus Plannck, ca.

[81] The Latin letter to Gabriel Sanchez, either the first or second Roman editions, was translated into Italian ottava rima by Giuliano Dati, a popular poet of the time, at the request of Giovanni Filippo dal Legname, secretary to Ferdinand II.