Power dividers and directional couplers

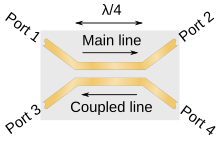

They couple a defined amount of the electromagnetic power in a transmission line to a port enabling the signal to be used in another circuit.

This technique is favoured at the microwave frequencies where transmission line designs are commonly used to implement many circuit elements.

These include providing a signal sample for measurement or monitoring, feedback, combining feeds to and from antennas, antenna beam forming, providing taps for cable distributed systems such as cable TV, and separating transmitted and received signals on telephone lines.

However, the device is not normally used in this mode and port 4 is usually terminated with a matched load (typically 50 ohms).

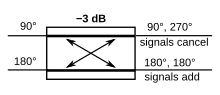

Coupling factor is a negative quantity, it cannot exceed 0 dB for a passive device, and in practice does not exceed −3 dB since more than this would result in more power output from the coupled port than power from the transmitted port – in effect their roles would be reversed.

While different designs may reduce the variance, a perfectly flat coupler theoretically cannot be built.

However, in a practical device the amplitude balance is frequency dependent and departs from the ideal 0 dB difference.

However, like amplitude balance, the phase difference is sensitive to the input frequency and typically will vary a few degrees.

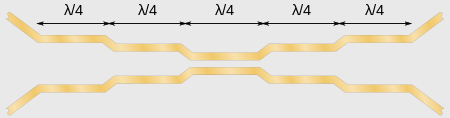

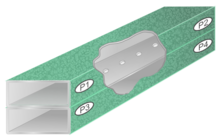

However, tightly coupled lines can be produced in air stripline which also permits manufacture by printed planar technology.

For a λ/4 coupled-line the total delay length is λ/2 so the second signal is inverted and this gives a maximum response on the coupled port.

This style of coupler is good for implementing in high-power, air dielectric, solid bar formats as the rigid structure is easy to mechanically support.

[22][23] The construction of the Lange coupler is similar to the interdigital filter with paralleled lines interleaved to achieve the coupling.

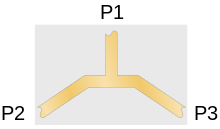

It can be shown that it is not theoretically possible to simultaneously match all three ports of a passive, lossless three-port and poor isolation is unavoidable.

The input is fed to both lines in parallel and the outputs are terminated with twice the system impedance bridged between them.

The reason for this is that at each combiner half the input power goes to port 4 and is dissipated in the termination load.

Using multiple holes allows the bandwidth to be extended by designing the sections as a Butterworth, Chebyshev, or some other filter class.

Design criteria are to achieve a substantially flat coupling together with high directivity over the desired band.

[36] The Schwinger reversed-phase coupler is another design using parallel waveguides, this time the long side of one is common with the short side-wall of the other.

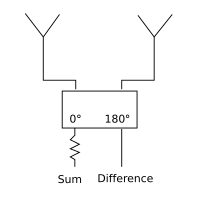

The magic tee is a four-port component which can perform the vector sum (Σ) and difference (Δ) of two coherent microwave signals.

The relative sign of the induced voltage and current determines the direction of the outgoing signal.

[46] A true hybrid divider/coupler with, theoretically, infinite isolation and directivity can be made from a resistive bridge circuit.

It has the disadvantage that it cannot be used with unbalanced circuits without the addition of transformers; however, it is ideal for 600 Ω balanced telecommunication lines if the insertion loss is not an issue.

Because of the symmetry of the directional coupler, the reverse injection will happen with the same possible modulation problems of signal generator F2 by F1.

[49] Applications of the hybrid include monopulse comparators, mixers, power combiners, dividers, modulators, and phased array radar antenna systems.

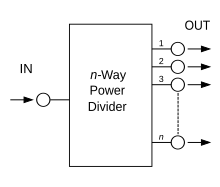

Multiport splitters with more than two output ports usually consist internally of a number of cascaded couplers.

This approach allows the use of numerous less expensive and lower-power amplifiers in the circuitry instead of a single high-power TWT.

To reject a signal from a given direction, or create the difference pattern for a monopulse radar, this is a good approach.

[56] Phase-difference couplers can be used to create beam tilt in a VHF FM radio station, by delaying the phase to the lower elements of an antenna array.

More generally, phase-difference couplers, together with fixed phase delays and antenna arrays, are used in beam-forming networks such as the Butler matrix, to create a radio beam in any prescribed direction.

[57] This article incorporates public domain material from Electronic Warfare and Radar Systems Engineering Handbook (report number TS 92-78).