Commissioners' Plan of 1811

Since its earliest days, the plan has been criticized for its monotony and rigidity, in comparison with irregular street patterns of older cities, but in recent years has been viewed more favorably by urban planners.

[16][17][notes 2] The French also built the nucleus of New Orleans, Louisiana on a grid, in part influenced by the Spanish Law of the Indies, which provided numerous practical models in the New World to copy from.

[14] The third instance of a privately developed grid in New York City came in 1788, when the long-established Bayard family, relatives of Peter Stuyvesant, hired surveyor Casimir Goerck to lay out streets in the portion of their estate west of Broadway, so the land could be sold in lots.

[26] The Council owned a great deal of land, primarily in the middle of the island, away from the Hudson and East Rivers, as a result of grants by the Dutch provincial government to the colony of New Amsterdam.

[26] To divide the Common Lands, as they were called, into sellable lots, and to lay out roads to service them, the Council hired Casimir Goerck, one of a handful of officially approved "city surveyors", to survey them.

In 1808, John Hunn, the city's street commissioner would comment that "The Surveys made by Mr. Goerck upon the Commons were effected through thickets and swamps, and over rocks and hills where it was almost impossible to produce accuracy of mensuration."

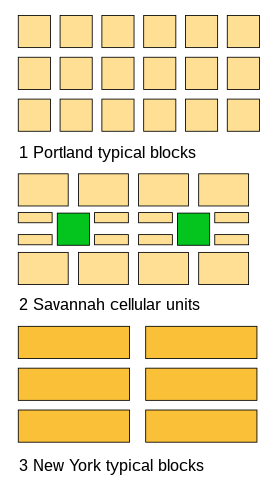

[50] At the meetings of the Commission, which were infrequent and usually not attended by all three men, their primary concern was what kind of layout the new area of the city should have, a rectilinear grid such as was used in Philadelphia; New Orleans; Savannah, Georgia; and Charleston, South Carolina, or a more complex system utilizing circles, arcs or other patterns, such as the plan Pierre Charles L'Enfant had used in laying out Washington, D.C.[1] In the end, the Commission decided on the gridiron as being the most practical and cost-effective, as "straight-sided and right-angled houses are the most cheap to build and the most convenient to live in.

Even though "[t]he Commissioners wrote as if all they cared about was protecting the investments of land developers and maintaining government-on-the-cheap ... the plan ... however, served to transform space into an expression of public philosophy," which emphasized equality and uniformity.

[4] The Commission expected that street frontage near the piers would be more valuable than the landlocked interior, the waterfront being the location of commerce and industry of the time, and so it would be to everyone's benefit to place avenues closer together at the island's edges.

"[74] In implementing the grid, existing buildings were allowed to remain where they were if at all possible, but if removal was necessary the owners would receive compensation from the city,[43] although appeal was available to a special panel appointed by the state's highest court.

By removing most of the topographical features which had once defined lot boundaries, the grid turned land into a commodity, which could be easily bought and sold in roughly equal-sized units, thus rationalizing the real estate market.

The primary one was the Grand Parade of 275 acres (111 ha) between 23rd and 33rd Street and between Third and Seventh Avenues, which was to be an open space slated for military drilling and for use as an assembly point in the event the city was invaded.

[87][88] One of the reasons behind the lack of inland open spaces in the plan was the belief of the Commissioners that the public would always have access to the "large arms of the sea which embrace Manhattan Island", the Hudson and East Rivers, as well as New York Harbor.

[94] These tasks, that of completing the survey with elevations, along with marking the actual positions of the notional streets of the plan, would take Randel another six years, until about 1817,[93] supervised by a committee of five alderman, as the Commission had disbanded once it had discharged its legal responsibility.

[131][134] The commission did extensive due diligence on the area, studying property ownership, population density, sanitation, the jobs of the residents, food and supplies distribution patterns, defensive needs, even the winds and weather of the region, and in 1868, a plan was published which called for grids in the valleys, but also streets, avenues and parks which conformed to the topography of the land.

Green said about the results of his commission's plan that it created "the only portion of Manhattan Island where any trace of its pristine beauty remains undesecrated and unrased [sic] by the leveling march of so-called 'public improvements.

[75] Walt Whitman, the poet and editor of The Brooklyn Eagle, said of it: "Our perpetual dead flat and streets cutting each other at right angles, are certainly the last thing in the world consistent with beauty of situation.

[151]Olmsted also said of it in 1858: The time will come when New York will be built-up, when all the grading and filling will be done, when the picturesquely varied rock formations of the island will have been converted into the foundations for rows of monotonous straight streets, and piles of erect angular buildings.

This original sin of the longitudinal avenues perpetually, yet meanly intersected, and of the organized sacrifice of the indicated alternative, the great perspectives from East to West, might still have earned forgiveness by some occasional departure from its pettifogging consistency.

Unfortunately, this plan, although possessing the merits of simplicity and directness, lacked entirely the equally essential elements of variety of picturesqueness, which demand a large degree of respect for the natural conformation of the land.

Urban activist Jane Jacobs noted "street[s] that go on and on ... dribbling into endless amorphous repetitions ... and finally petering into the utter anonymity of distances,"[149] and famed architect Frank Lloyd Wright wrote of its "deadly monotony," calling it a "man trap of gigantic dimensions.

Mumford wrote that: "With a T-square and a triangle, finally, the municipal engineer, without the slightest training as either an architect or a sociologist, could "plan" a metropolis ..."[1] and Montgomery Schuyler, another architecture critic, claimed that "We all agreed – all of us, that is, who pay attention to such things – that the Commissioners were public malefactors of high degree.

Unhappily, they were ... men devoid of all imagination,"[159] while historian Thomas Janvier, in his book In Old New York (1894), wrote of the "deplorable results" of "the excellently dull gentlemen",[160] and criticized the plan as only "a grind of money-making.

In an effort to escape criticism on the grounds of economy and practicality, the commissioners ignored well-known principles of civic design that would have brought variety in street vistas and resulted in focal points for sites for important buildings and use.

True enough, no one would have foreseen the rapid growth of the city and the changes in transportation and population that lessened the importance of the river-to-river cross streets while placing an intolerable load on the less numerous north–south avenues.

Writing in 1986, urban analyst David Schuyler said that "In 1811 the gridiron had been so widely accepted as the optimal street arrangement for a commercial city that the plan received only perfunctory treatment in the press – even though it had a dramatic effect on existing property lines.

"[167] The Citizens and Strangers Guide of 1814 said "The whole island has been surveyed and framed into extensive avenues and commodious streets, forming an important legacy to posterity, from which the most solid advantages may be anticipated,"[168] while another commentator from that year wrote "The arrangement of the original or lower part of the city ... is essentially defective.

"[173] Rafael Viñoly, a Uruguayan-born architect, called the grid "the best manifestation of American pragmatism in the creation of urban form," writing: It is the unified formula that controls and organizes the forces that make the city what it is, what it was, and what it will become ...

"[177] Similarly, economist Edward Glaeser, author of Triumph of the City (2011), wrote that "Manhattan's grid imposes clarity on the island's burbling chaos and enables ordinary pedestrians to negotiate New York's complex ecosystem.

[179]Finally, Roland Barthes, the French literary theorist, philosopher, linguist, critic, and semiotician, wrote in 1959: "This is the purpose of New York's geometry: that each individual should be poetically the owner of the capital of the world.