Common Sense

Common Sense[1] is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies.

Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political arguments to encourage common people in the Colonies to fight for egalitarian government.

[4] Common Sense made public a persuasive and impassioned case for independence, which had not yet been given serious intellectual consideration in either Britain or the American colonies.

"[10] Paine quickly engrained himself in the Philadelphia newspaper business, and began writing Common Sense in late 1775 under the working title of Plain Truth.

[12] Paine, overjoyed with its success, endeavored to collect his share of the profits and donate them to purchase mittens for General Montgomery's troops, then encamped in frigid Quebec.

Paine secured the assistance of the Bradford brothers, publishers of The Pennsylvania Evening Post, and released his new edition, featuring several appendices and additional writings.

This set off a month-long public debate between Bell and the still-anonymous Paine, conducted within the pages and advertisements of the Pennsylvania Evening Post, with each party charging the other with duplicity and fraud.

[citation needed] The publicity generated by the initial success and compounded by the publishing disagreements propelled the pamphlet to incredible sales and circulation.

[22] Writing in 1956, Richard Gimbel estimated, in terms of circulation and impact, that an "equivalent sale today, based on the present population of the United States, would be more than six-and-one-half million copies within the short space of three months".

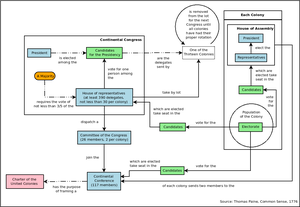

Of more worth is one honest man to society and in the sight of God, than all the crowned ruffians that ever lived.Paine also attacks one type of "mixed state," the constitutional monarchy promoted by John Locke, in which the powers of government are separated between a Parliament or Congress, which makes the laws, and a monarch, who executes them.

Charles Inglis, then the Anglican cleric of Trinity Church in New York, responded to Paine on behalf of colonists loyal to the Crown with a treatise entitled The True Interest of America Impartially Stated.

On the Radical democratic society promoted by Common Sense, Chalmers quoted Montesquieu in saying that "No government is so subject to Civil Wars and Intestine Commotions".

John Adams, who would succeed George Washington to become the new nation's second president, in his Thoughts on Government wrote that Paine's ideal sketched in Common Sense was "so democratical, without any restraint or even an attempt at any equilibrium or counter poise, that it must produce confusion and every evil work.

Writing as "The Forester," he responded to Cato and other critics in the pages of Philadelphian papers with passion and declared again in sweeping language that their conflict was not only with Great Britain but also with the tyranny inevitably resulting from monarchical rule.

[30] Heavy advertisement by both Bell and Paine and the immense publicity created by their publishing quarrel made Common Sense an immediate sensation not only in Philadelphia but also across the Thirteen Colonies.

Early "reviewers" (mainly letter excerpts published anonymously in colonial newspapers) touted the clear and rational case for independence put forth by Paine.

[32] Paine's vision of a radical democracy, unlike the checked and balanced nation later favored by conservatives like John Adams, was highly attractive to the popular audience which read and reread Common Sense.

In the months leading up to the Declaration of Independence, many more reviewers noted that the two main themes (direct and passionate style and calls for individual empowerment) were decisive in swaying the Colonists from reconciliation to rebellion.

[33] While Paine focused his style and address towards the common people, the arguments he made touched on prescient debates of morals, government, and the mechanisms of democracy.

[34] That gave Common Sense a "second life" in the very public call-and-response nature of newspaper debates made by intellectual men of letters throughout Philadelphia.

Some, like A. Owen Aldridge, emphasize that Common Sense could hardly be said to embody a particular ideology, and that "even Paine himself may not have been cognizant of the ultimate source of many of his concepts."

[38] Many have noted that Paine's skills were chiefly in persuasion and propaganda and that no matter the content of his ideas, the fervor of his conviction and the various tools he employed on his readers (such as asserting his Christianity when he really was a Deist), Common Sense was bound for success.