The Communist Manifesto

Marx and Engels combine philosophical materialism with the Hegelian dialectical method in order to analyze the development of European society through its modes of production, including primitive communism, antiquity, feudalism, and capitalism, noting the emergence of a new, dominant class at each stage.

They argue that capital's need for a flexible labour force dissolves the old relations, and that its global expansion in search of new markets creates "a world after its own image".

Marx and Engels propose the following transitional policies: the abolition of private property in land and inheritance; introduction of a progressive income tax; confiscation of rebels' property; nationalisation of credit, communication, and transport; expansion and integration of industry and agriculture; enforcement of universal obligation of labour; and provision of universal education and abolition of child labour.

[5] The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism.

While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class.

At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation.

On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at Ostend in Belgium, and a few days later, gathered at the Soho, London headquarters of the German Workers' Education Association to attend the Congress.

Over the next ten days, intense debate raged between League functionaries; Marx eventually dominated the others and, overcoming "stiff and prolonged opposition",[7] in Harold Laski's words, secured a majority for his programme.

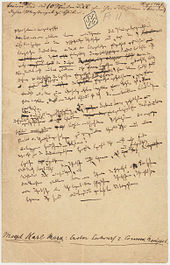

Working only intermittently on the Manifesto, he spent much of his time delivering lectures on political economy at the German Workers' Education Association, writing articles for the Deutsche-Brüsseler-Zeitung [de], and giving a long speech on free trade.

Subsequently, having not heard from Marx for nearly two months, the Central Committee of the Communist League sent him an ultimatum on 24 or 26 January, demanding he submit the completed manuscript by 1 February.

Although Laski does not disagree, he suggests that Engels underplays his own contribution with characteristic modesty and points out the "close resemblance between its substance and that of the [Principles of Communism]".

Laski argues that while writing the Manifesto, Marx drew from the "joint stock of ideas" he developed with Engels "a kind of intellectual bank account upon which either could draw freely".

[8] In late February 1848, the Manifesto was anonymously published by the Workers' Educational Association (Kommunistischer Arbeiterbildungsverein), based at 46 Liverpool Street, in the Bishopsgate Without area of the City of London.

In November 1850 the Manifesto of the Communist Party was published in English for the first time when George Julian Harney serialised Helen Macfarlane's translation in his Chartist newspaper The Red Republican.

Its influence in the Europe-wide Revolutions of 1848 was restricted to Germany, where the Cologne-based Communist League and its newspaper Neue Rheinische Zeitung, edited by Marx, played an important role.

For Engels, the revolution was "forced into the background by the reaction that began with the defeat of the Paris workers in June 1848, and was finally excommunicated 'by law' in the conviction of the Cologne Communists in November 1852".

Hobsbawm says that by November 1850 the Manifesto "had become sufficiently scarce for Marx to think it worth reprinting section III [...] in the last issue of his [short-lived] London magazine".

Thus in 1872 Marx and Engels rushed out a new German-language edition, writing a preface that identified that several portions that became outdated in the quarter century since its original publication.

Over the next forty years, as social-democratic parties rose across Europe and parts of the world, so did the publication of the Manifesto alongside them, in hundreds of editions in thirty languages.

The first Chinese edition of the book was translated by Zhu Zhixin after the 1905 Russian Revolution in a Tongmenghui newspaper along with articles on socialist movements in Europe, North America, and Japan.

On the other hand, small, dedicated militant parties and Marxist sects in the West took pride in knowing the theory; Hobsbawm says: "This was the milieu in which 'the clearness of a comrade could be gauged invariably from the number of earmarks on his Manifesto'".

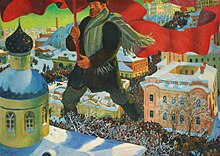

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the Vladimir Lenin-led Bolsheviks to power in Russia, the world's first socialist state was founded explicitly along Marxist lines.

Therefore the widespread dissemination of Marx and Engels' works became an important policy objective; backed by a sovereign state, the CPSU had relatively inexhaustible resources for this purpose.

In Manhattan, a prominent Fifth Avenue store put copies of this choice new edition in the hands of shop-window mannequins, displayed in come-hither poses and fashionable décolletage".

"With the clarity and brilliance of genius, this work outlines a new world-conception, consistent materialism, which also embraces the realm of social life; dialectics, as the most comprehensive and profound doctrine of development; the theory of the class struggle and of the world-historic revolutionary role of the proletariat—the creator of a new, communist society."

In a special issue of the Socialist Register commemorating the Manifesto's 150th anniversary, Peter Osborne argued that it was "the single most influential text written in the nineteenth century".

It is still able to explain, as mainstream economists and sociologists cannot, today's world of recurrent wars and repeated economic crisis, of hunger for hundreds of millions on the one hand and 'overproduction' on the other.

[22] In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist Eduard Bernstein distinguished between "immature" early Marxism—as exemplified by The Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Engels in their youth—that he opposed for its violent Blanquist tendencies and later "mature" Marxism that he supported.

[23] This latter form refers to Marx in his later life seemingly claiming that socialism, under certain circumstances, could be achieved through peaceful means through legislative reform in democratic societies.

[28] However, as Eric Hobsbawm noted: [W]hile there is no doubt that Marx at this time shared the usual townsman's contempt for, as well as ignorance of, the peasant milieu, the actual and analytically more interesting German phrase ("dem Idiotismus des Landlebens entrissen") referred not to "stupidity" but to "the narrow horizons", or "the isolation from the wider society" in which people in the countryside lived.