List of communist ideologies

Parties with a Marxist–Leninist understanding of the historical development of socialism advocate for the nationalisation of natural resources and monopolist industries of capitalism and for their internal democratization as part of the transition to workers' control.

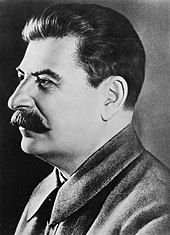

[54] Although Stalin himself repudiated any qualitatively original contribution to Marxism, the communist movement usually credits him with systematizing and expanding the ideas of Lenin into the ideology of Marxism–Leninism as a distinct body of work.

It supported proletarian internationalism[63] and another communist revolution in the Soviet Union which Trotsky claimed had become a degenerated worker's state under the leadership of Stalin in which class relations had re-emerged in a new form,[64][65] rather than the dictatorship of the proletariat.

[76][77] Trotsky's politics differed sharply from those of Stalin and Mao, most importantly in declaring the need for an international proletarian revolution (rather than socialism in one country)[78] and unwavering support for a true dictatorship of the proletariat-based on democratic principles.

As the Sino-Soviet split in the international communist movement turned toward open hostility, China portrayed itself as a leader of the underdeveloped world against the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union.

From the 1960s, groups that called themselves Maoist, or which upheld Marxism–Leninism–Mao Zedong Thought, were not unified around a common understanding of Maoism and had instead their own particular interpretations of the political, philosophical, economical and military works of Mao.

The Albanians were able to win over a large share of the Maoists, mainly in Latin America such as the Popular Liberation Army and the Marxist–Leninist Communist Party of Ecuador, but it also had a significant international following in general.

[147][148][149] It became the only country in the Balkans to resist pressure from Moscow to join the Warsaw Pact and remained "socialist, but independent" right up until the collapse of Soviet socialism in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

[186] The Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) of South Africa, founded in 2013 by Julius Malema, claim to take significant inspiration from Sankara in terms of both style and ideology.

With elements of regulated market economics as well as an improved human rights record, it represented a quiet reform and deviation from the Stalinist principles applied to Hungary in the previous decade.

[196] Husakism (Czech: husákismus; Slovak: husákizmus) is an ideology connected with the politician Gustáv Husák of Communist Czechoslovakia which describes his policies of "normalization"[197] and federalism,[198] while following a neo-Stalinist line.

[209] Libertarian Marxism includes currents such as autonomism, council communism, De Leonism, Lettrism, parts of the New Left, Situationism, Freudo-Marxism (a form of psychoanalysis),[210] Socialisme ou Barbarie}[211] and workerism.

[224] The group confronted issues such as the problem of the National Question within the Austro-Hungarian Empire,[225]: 295–298 [226] the rise of the interventionist state and the changing class-structure of early 20th century capitalist societies.

[236] The French ultra-gauche, has a stronger meaning in that language and is used to define a movement that still exists today: a branch of left communism developed from theorists such as Bordiga, Rühle, Pannekoek, Gorter, and Mattick, and continuing with more recent writers, such as Jacques Camatte and Gilles Dauvé.

Later, post-Marxist and anarchist tendencies became significant after influence from the Situationists, the failure of Italian far-left movements in the 1970s, and the emergence of a number of important theorists including Antonio Negri,[232] who had contributed to the 1969 founding of Potere Operaio as well as Mario Tronti, Paolo Virno, Sergio Bologna and Franco "Bifo" Berardi.

They suggested that modern society's wealth was produced by unaccountable collective work, which in advanced capitalist states as the primary force of change in the construct of capital, and that only a little of this was redistributed to the workers in the form of wages.

Other theorists including Mariarosa Dalla Costa and Silvia Federici emphasised the importance of feminism and the value of unpaid female labour to capitalist society, adding these to the theory of Autonomism.

[242][243] Negri and Michael Hardt argue that network power constructs are the most effective methods of organization against the neoliberal regime of accumulation and predict a massive shift in the dynamics of capital into a 21st century empire.

[248] Notable figures in this tradition include György Lukács,[249][250] Karl Korsch,[251][250] Antonio Gramsci,[250] Herbert Marcuse, Jean-Paul Sartre,[252] Louis Althusser,[253] and the members of the Frankfurt School.

[283] The success of the De Leonist plan depends on achieving majority support among the people both in the workplaces and at the polls,[284][285] in contrast to the Leninist notion that a small vanguard party should lead the working class to carry out the revolution.

[288][291] Essential to situationist theory was the concept of the spectacle,[290][292] a unified critique of advanced capitalism of which a primary concern was the progressively increasing tendency towards the expression and mediation of social relations through objects.

[288][294] The situationists recognized that capitalism had changed since Marx's formative writings, but maintained that his analysis of the capitalist mode of production remained fundamentally correct; they rearticulated and expanded upon several classical Marxist concepts, such as his theory of alienation.

[288] In their expanded interpretation of Marxist theory, the situationists asserted that the misery of social alienation and commodity fetishism were no longer limited to the fundamental components of capitalist society,[293][295] but had now in advanced capitalism spread themselves to every aspect of life and culture.

Marxist humanists contend that there is continuity between the early philosophical writings of Marx, in which he develops his theory of alienation, and the structural description of capitalist society found in his later works such as Das Kapital.

[313] Primitive communism is a way of describing the gift economies of hunter-gatherers throughout history, where resources and property hunted and gathered are shared with all members of a group, in accordance with individual needs.

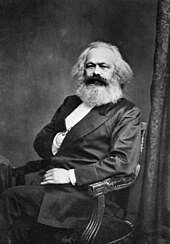

In political sociology and anthropology, it is also a concept often credited to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels for originating, who wrote that hunter-gatherer societies were traditionally based on egalitarian social relations and common ownership.

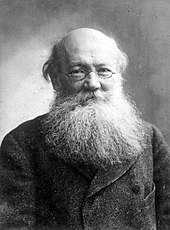

[322][323][324] Important theorists to anarcho-communism include Alexander Berkman,[325] Murray Bookchin, Noam Chomsky, Errico Malatesta,[326] Emma Goldman, Ricardo Flores Magón, and Nestor Makhno.

It was a mixture of all of this, a cocktail which was mixed in the mountain and crystallized in the combat force of the EZLN…[368]In 1998, Michael Löwy identified five "threads" of what he referred to as the Zapatismo "carpet":[369] In 1992, Juche replaced Marxism-Leninism in the revised North Korean constitution as the official state ideology.

[378][379] While a major focus of the ideology was ending colonial relationships on the African continent, many of the ideas were utopian, diverting the scientific nature of the Marxist political analysis which it claims to support.

[391] The defining common ground is the contention that "the crises of contemporary liberal capitalist societies—ecological degradation, financial turmoil, the loss of trust in the political class, exploding inequality—are systemic, interlinked, not amenable to legislative reform, and require "revolutionary" solutions".