Comparative advantage

[1] Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress.

[8]Writing several decades after Smith in 1808, Robert Torrens articulated a preliminary definition of comparative advantage as the loss from the closing of trade: [I]f I wish to know the extent of the advantage, which arises to England, from her giving France a hundred pounds of broadcloth, in exchange for a hundred pounds of lace, I take the quantity of lace which she has acquired by this transaction, and compare it with the quantity which she might, at the same expense of labour and capital, have acquired by manufacturing it at home.

The lace that remains, beyond what the labour and capital employed on the cloth, might have fabricated at home, is the amount of the advantage which England derives from the exchange.

[9]In 1814 the anonymously published pamphlet Considerations on the Importation of Foreign Corn featured the earliest recorded formulation of the concept of comparative advantage.

[10][11] Torrens would later publish his work External Corn Trade in 1815 acknowledging this pamphlet author's priority.

[10] In 1817, David Ricardo published what has since become known as the theory of comparative advantage in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

[12] In a famous example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries, Portugal and England, each producing two goods of identical quality.

[18] In 1930 Austrian-American economist Gottfried Haberler detached the doctrine of comparative advantage from Ricardo's labor theory of value and provided a modern opportunity cost formulation.

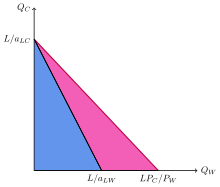

Haberler implemented this opportunity-cost formulation of comparative advantage by introducing the concept of a production possibility curve into international trade theory.

Adding commodities in order to have a smooth continuum of goods is the major insight of the seminal paper by Dornbusch, Fisher, and Samuelson.

Deardorff argues that the insights of comparative advantage remain valid if the theory is restated in terms of averages across all commodities.

"Deardorff's general law of comparative advantage" is a model incorporating multiple goods which takes into account tariffs, transportation costs, and other obstacles to trade.

[27][28] This was based on a wide range of assumptions: Many countries; Many commodities; Several production techniques for a product in a country; Input trade (intermediate goods are freely traded); Durable capital goods with constant efficiency during a predetermined lifetime; No transportation cost (extendable to positive cost cases).

"[29] However, McKenzie and later researchers could not produce a general theory which includes traded input goods because of the mathematical difficulty.

[30] As John Chipman points it, McKenzie found that "introduction of trade in intermediate product necessitates a fundamental alteration in classical analysis.

"[31] Durable capital goods such as machines and installations are inputs to the productions in the same title as part and ingredients.

Deardorff examines 10 versions of definitions in two groups but could not give a general formula for the case with intermediate goods.

[32][33] Comparative advantage is a theory about the benefits that specialization and trade would bring, rather than a strict prediction about actual behavior.

Testing the Ricardian model for instance involves looking at the relationship between relative labor productivity and international trade patterns.

Considering the durability of different aspects of globalization, it is hard to assess the sole impact of open trade on a particular economy.

[citation needed] Daniel Bernhofen and John Brown have attempted to address this issue, by using a natural experiment of a sudden transition to open trade in a market economy.

Under Western military pressure, Japan opened its economy to foreign trade through a series of unequal treaties.

[39][40] A prediction of a two-country Ricardian comparative advantage model is that countries will export goods where output per worker (i.e. productivity) is higher.

Dosi et al. (1988)[43] conducted a book-length empirical examination that suggests that international trade in manufactured goods is largely driven by differences in national technological competencies.

Dornbusch et al. (1977)[44] generalized the theory to allow for such a large number of goods as to form a smooth continuum.

Based in part on these generalizations of the model, Davis (1995)[45] provides a more recent view of the Ricardian approach to explain trade between countries with similar resources.

More recently, Golub and Hsieh (2000)[46] presents modern statistical analysis of the relationship between relative productivity and trade patterns, which finds reasonably strong correlations, and Nunn (2007)[47] finds that countries that have greater enforcement of contracts specialize in goods that require relationship-specific investments.

Markusen et al. (1994)[49] reports the effects of moving away from autarky to free trade during the Meiji Restoration, with the result that national income increased by up to 65% in 15 years.

Several arguments have been advanced against using comparative advantage as a justification for advocating free trade, and they have gained an audience among economists.

He argues that comparative advantage relies on the assumption of constant returns, which he states is not generally the case.

In case I (diamonds), each country spends 3600 hours to produce a mixture of cloth and wine.

In case II (squares), each country specializes in its comparative advantage, resulting in greater total output.