Comparative illusion

[5] Mario Montalbetti's 1984 Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation has been credited as being the first to note these sorts of sentences;[5] in his prologue he gives acknowledgements to Hermann Schultze "for uttering the most amazing */?

[10] Parallel examples with Russia instead of Berlin were briefly discussed in psycholinguistic work in the 1990s and 2000s by Thomas Bever and colleagues.

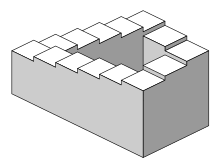

[13] He wrote:[14] All these stimuli [i.e., these sentences, Penrose stairs, and the Shepard tone] involve familiar and coherent local cues whose global integration is contradictory or impossible.

[30] Alexis Wellwood and colleagues have found in experiments that the illusion of grammaticality is greater when the sentence's predicate is repeatable.

[34] However, Christensen's study on comparative illusions in Danish did not find a significant difference in acceptability for sentences with repeatable predicates (a) and those without (b).

'The lexical ambiguity of the English quantifier more has led to a hypothesis where the acceptability of CIs is due to people reinterpreting a "comparative" more as an "additive" more.

[29] Christensen found no significant difference in acceptability for Danish CIs with flere ("more") compared to those with færre ("fewer").

[37]In a study of Danish speakers, CIs with prepositional sentential adverbials like om aftenen "in the evening" were found to be less acceptable than those without.

[38] Comparatives in Bulgarian can optionally have the degree operator колкото (kolkoto); sentences with this morpheme (a) are immediately found unacceptable but those without it (b) produce the same illusion of acceptability.

Townsend and Bever have posited that Escher sentences get perceived as acceptable because they are an apparent blend of two grammatical templates.

[41] Wellwood and colleagues have noted in response that the possibility of each clause being grammatical in a different sentence (a, b) does not guarantee a blend (c) would be acceptable.

[42] Wellwood and colleagues also interpret Townsend and Bever's theory as requiring a shared lexical element in each template.

If this version is right, they predict (c) would be viewed as less acceptable due to the ungrammaticality of (b):[42]Wellwood and colleagues, based on their experimental results, have rejected Townsend and Bever's hypothesis and instead support their event comparison hypothesis, which states that comparative illusions are due to speakers reinterpreting these sentences as discussing a comparison of events.

"[44] Phillips and colleagues have discussed other grammatical illusions with respect to attraction, case in German, binding, and negative polarity items; speakers initially find such sentences acceptable, but later realize they are ungrammatical.