Competitive inhibition

Km also plays a part in indicating the tendency of the substrate to bind the enzyme.

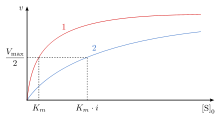

As a result, competitive inhibition alters only the Km, leaving the Vmax the same.

[4][5][6] Most competitive inhibitors function by binding reversibly to the active site of the enzyme.

[7] This, however, is a misleading oversimplification, as there are many possible mechanisms by which an enzyme may bind either the inhibitor or the substrate but never both at the same time.

In competitive inhibition, the inhibitor resembles the substrate, taking its place and binding to the active site of an enzyme.

It is structurally similar to the coenzyme, folate, which binds to the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase.

These fatty acids inhibitors have been used as drugs to relieve pain because they can act as the substrate, and bind to the enzyme, and block prostaglandins.

[9] An example of non-drug related competitive inhibition is in the prevention of browning of fruits and vegetables.

For example, tyrosinase, an enzyme within mushrooms, normally binds to the substrate, monophenols, and forms brown o-quinones.

These inhibitory compounds added to the produce keep it fresh for longer periods of time by decreasing the binding of the monophenols that cause browning.

If it is reversible inhibition, then effects of the inhibitor can be overcome by increasing substrate concentration.

For example, strychnine acts as an allosteric inhibitor of the glycine receptor in the mammalian spinal cord and brain stem.

Glycine is a major post-synaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter with a specific receptor site.

) of the reaction is unchanged, while the apparent affinity of the substrate to the binding site is decreased (the

This means the binding affinity for the enzyme is decreased, but it can be overcome by increasing the concentration of the substrate.

After an accidental ingestion of a contaminated opioid drug desmethylprodine, the neurotoxic effect of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) was discovered.

MPTP is able to cross the blood brain barrier and enter acidic lysosomes.

[13] MPTP is biologically activated by MAO-B, an isozyme of monoamine oxidase (MAO) which is mainly concentrated in neurological disorders and diseases.

Cells in the central nervous system (astrocytes) include MAO-B that oxidizes MPTP to 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+), which is toxic.

[13] MPP+ eventually travels to the extracellular fluid by a dopamine transporter, which ultimately causes the Parkinson's symptoms.

However, competitive inhibition of the MAO-B enzyme or the dopamine transporter protects against the oxidation of MPTP to MPP+.

A few compounds have been tested for their ability to inhibit oxidation of MPTP to MPP+ including methylene blue, 5-nitroindazole, norharman, 9-methylnorharman, and menadione.

[14] These demonstrated a reduction of neurotoxicity produced by MPTP.Sulfa drugs also act as competitive inhibitors.

For example, sulfanilamide competitively binds to the enzyme in the dihydropteroate synthase (DHPS) active site by mimicking the substrate para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA).

[15] This prevents the substrate itself from binding which halts the production of folic acid, an essential nutrient.

Therefore, because of sulfa drugs' competitive inhibition, they are excellent antibacterial agents.

It is generally assumed that this behavior is indicative of both compounds binding at the same site, but that is not strictly necessary.

As with the derivation of the Michaelis–Menten equation, assume that the system is at steady-state, i.e. the concentration of each of the enzyme species is not changing.

, and the velocity is measured under conditions in which the substrate and inhibitor concentrations do not change substantially and an insignificant amount of product has accumulated.

Replacing and combining terms finally yields the conventional form: To compute the concentration of competitive inhibitor

2 H

5 OH ) serves as a competitive inhibitor to methanol ( CH

3 OH ) and ethylene glycol ( (CH 2 OH) 2 ) for the enzyme alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver when present in large amounts. For this reason, ethanol is sometimes used as a means to treat or prevent toxicity following accidental ingestion of these chemicals.