Compulsory figures

They are the "circular patterns which skaters trace on the ice to demonstrate skill in placing clean turns evenly on round circles".

These figures continued to dominate the sport, although they steadily declined in importance, until the International Skating Union (ISU) voted to discontinue them as a part of competitions in 1990.

[9] According to writer Ellyn Kestnbaum, the Edinburgh Skating Club required prospective members to pass proficiency tests in what became compulsory figures.

[13] The Mohawk, renamed in Canada to the C Step in 2020, a two-foot turn on the same circle, most likely originated in North America.

Figure Skating, adopted a series of movements used during competitions between skaters from the U.S. and Canada.

Athletes were unable to support themselves financially, so as Kestnbaum put it, "thus making it impossible for those who had to earn a living by other means to attain the same level of skill as those who were independently wealthy or who practiced professions that allowed for flexible scheduling".

[26] According to Kestnbaum, this had implications for attaining proficiency in compulsory figures, which required long hours of practice and purchasing time at private rinks and clubs.

[26] In 1897, the ISU adopted a schedule of 41 school figures, each of increasing difficulty, which was proposed by the British.

They remained the standard compulsory figures used throughout the world in proficiency testing and competitions until 1990, and U.S.

After World War II, more countries were sending skaters to international competitions, so the ISU cut the number of figures to a maximum of six due to the extended time it took to judge them all.

[18] The elimination of figures resulted in the increase of focus on the free skating segment and in the domination of younger girls in the sport.

[38] He states, "As scales are the material by which musicians develop the facile technique required to perform major competitions, so compulsory figures were viewed as the material by which skaters develop the facile required for free-skating programs".

[25] The patterns skaters left on the ice, rather than the shapes the body made executing them, became the focus of artistic expression in figure skating into the 20th century.

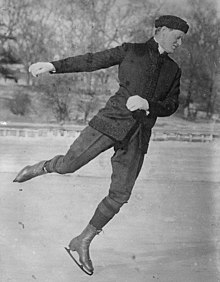

[38] Skaters had to execute figures by positioning themselves to precisely control the edges of one blade of their skates by leaning in or out, moving forward or backward.

[2] Olympic champion Debi Thomas stated, about the execution of figures, "It takes incredible strength and control.

[41] The highest quality figures had tracings on top of each other; their edges were placed precisely, and the turns lined up exactly.

[42] He expected skaters to trace figures without looking down at them because it gave "a very slovenly appearance",[42] and recommended that they not use their arms excessively or for balance like tightrope walkers.

The balance leg also should be bent only slightly, since he believed bending it too much removed its usefulness and appeared clumsy.

[43] Writer Ellyn Kestnbaum notes that skaters who were adept at performing compulsory figures had to practice for hours to have precise body control and to become "intimately familiar with how subtle shifts in the body's balance over the blade affected the tracings left on the ice".

Each circle's diameter had to be about three times the skater's height,[b] and the radii of all half-circles had to be approximately the same length.

[47] Curves, which are parts of circles, had to be performed with an uninterrupted tracing and with a single clean edge, with no subcurves or wobbles.

[49] He states, "It is the control of these circles that gives strength and power, and the holding of the body in the proper and graceful attitudes, while it is the execution of these large circles, changes of edges, threes and double-threes, brackets, loops, rockers and counters, which makes up the art of skating".

Skaters could choose the exact point in which they placed their foot in this zone, although it typically was just after the long axis, with the full weight of the body on the skate.

[14] Altered forms of the Q figure often do not look like the letter "q", but "simply employ a serpentine line and a three turn".

[14] Since the goal of figures is drawing an exact shape on the ice, the skater had to concentrate on the depth of the turn (how much the turn extends into or out of the circle), the integrity of the edges and cusps (round-patterned edges leading into or out of the circle), and its shape.

[45] After the skaters completed tracing figures, the judges scrutinized the circles made, and the process was repeated twice more.

[45] According to Louise Radnofsky, who claimed that the execution of figures could be "very boring—and worse to watch", the most exciting physical move was a change of direction.

Judges took note of the following: scrapes, double tracks that indicated that both edges of their blades were in contact with the ice simultaneously, deviations from a perfect circle, how closely the tracings from each repetition followed each other, how well the loops lined up, and other errors.