Condemnations of 1210–1277

[2] The Condemnation of 1210 was issued by the provincial synod of Sens, which included the Bishop of Paris as a member (at the time Pierre II de la Chapelle [fr]).

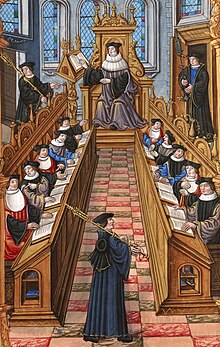

[3] The writings of a number of medieval scholars were condemned, apparently for pantheism, and it was further stated that: "Neither the books of Aristotle on natural philosophy or their commentaries are to be read at Paris in public or secret, and this we forbid under penalty of excommunication.

[4] The University of Toulouse (founded in 1229) tried to capitalise on the situation by advertising itself to students: "Those who wish to scrutinize the bosom of nature to the inmost can hear the books of Aristotle which were forbidden at Paris.

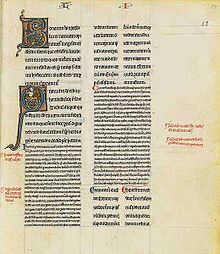

[6] The banned propositions included: Those who "knowingly" taught or asserted them as true would suffer automatic excommunication, with the implied threat of the medieval Inquisition if they persisted.

[6] It is not known which of these statements were "taught knowingly" or "asserted" by teachers at Paris,[8] although Siger of Brabant and his radical Averroist colleagues at the Faculty of Arts were targets.

"Not only did Tempier investigate but in only three weeks, on his own authority, he issued a condemnation of 219 propositions drawn from many sources, including, apparently, the works of Thomas Aquinas, some of whose ideas found their way onto the list.

In addition to the 219 errors, the condemnation also covered Andreas Capellanus's De amore, and unnamed or unidentified treatises on geomancy, necromancy, witchcraft, or fortunetelling.

[1] Siger of Brabant and Boethius of Dacia have been singled out as the most prominent targets of the 1277 censure, even though their names are not found in the document itself, appearing instead in the rubrics of only two of the many manuscripts that preserve the condemnation.

[11] Although the Aristotelian system viewed propositions such as the existence of a vacuum to be ridiculously untenable, belief in Divine Omnipotence sanctioned them as possible, whilst waiting for science to confirm them as true.

According to Duhem, "if we must assign a date for the birth of modern science, we would, without doubt, choose the year 1277 when the bishop of Paris solemnly proclaimed that several worlds could exist, and that the whole of heavens could, without contradiction, be moved with a rectilinear motion.

[1] "Duhem believed that Tempier, with his insistence of God's absolute power, had liberated Christian thought from the dogmatic acceptance of Aristotelianism, and in this way marked the birth of modern science.

[20] Since the theologians had asserted that Aristotle had erred in theology, and pointed out the negative consequences of uncritical acceptance of his ideas, scholastic philosophers such as Duns Scotus and William of Ockham (both Franciscan friars) believed he might also be mistaken in matters of philosophy.

[20] The Scotist and Ockhamist movements set Scholasticism on a different path from that of Albert the Great and Aquinas, and the theological motivation of their philosophical arguments can be traced back to 1277.

[24] It has been suggested that the new philosophy of nature that emerged from the rise of Skepticism following the Condemnations, contained "the seeds from which modern science could arise in the early seventeenth century.