Condorcet method

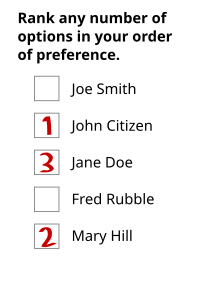

[2][3] The head-to-head elections need not be done separately; a voter's choice within any given pair can be determined from the ranking.

[4][5] Some elections may not yield a Condorcet winner because voter preferences may be cyclic—that is, it is possible that every candidate has an opponent that defeats them in a two-candidate contest.

A considerable portion of the literature on social choice theory is about the properties of this method since it is widely used and is used by important organizations (legislatures, councils, committees, etc.).

It is not practical for use in public elections, however, since its multiple rounds of voting would be very expensive for voters, for candidates, and for governments to administer.

For most Condorcet methods, those counts usually suffice to determine the complete order of finish (i.e. who won, who came in 2nd place, etc.).

For example, with Copeland's method, it would not be rare for two or more candidates to win the same number of pairings, when there is no Condorcet winner.

They can also be found by conducting a series of pairwise comparisons, using the procedure given in Robert's Rules of Order described above.

This occurs as a result of a kind of tie known as a majority rule cycle, described by Condorcet's paradox.

While any Condorcet method will elect Nashville as the winner, if instead an election based on the same votes were held using first-past-the-post or instant-runoff voting, these systems would select Memphis[footnotes 1] and Knoxville[footnotes 2] respectively.

If we changed the basis for defining preference and determined that Memphis voters preferred Chattanooga as a second choice rather than as a third choice, Chattanooga would be the Condorcet winner even though finishing in last place in a first-past-the-post election.

Nonetheless a cycle is always possible, and so every Condorcet method should be capable of determining a winner when this contingency occurs.

There are countless ways in which this can be done, but every Condorcet method involves ignoring the majorities expressed by voters in at least some pairwise matchings.

These include Smith-Minimax (Minimax but done only after all candidates not in the Smith set are eliminated), Ranked Pairs, and Schulze.

A more sophisticated two-stage process is, in the event of a cycle, to use a separate voting system to find the winner but to restrict this second stage to a certain subset of candidates found by scrutinizing the results of the pairwise comparisons.

These methods include: Ranked Pairs and Schulze are procedurally in some sense opposite approaches (although they very frequently give the same results): Minimax could be considered as more "blunt" than either of these approaches, as instead of removing defeats it can be seen as immediately removing candidates by looking at the strongest defeats (although their victories are still considered for subsequent candidate eliminations).

When the pairwise counts are arranged in a matrix in which the choices appear in sequence from most popular (top and left) to least popular (bottom and right), the winning Kemeny score equals the sum of the counts in the upper-right, triangular half of the matrix (shown here in bold on a green background).

Calculating every Kemeny score requires considerable computation time in cases that involve more than a few choices.

However, fast calculation methods based on integer programming allow a computation time in seconds for some cases with as many as 40 choices.

Then it considers the second largest majority, who rank A over B, and places A ahead of B in the order of finish.

An equivalent definition is to find the order of finish that minimizes the size of the largest reversed majority.

See the discussion of MinMax, MinLexMax and Ranked Pairs in the 'Motivation and uses' section of the Lexicographical Order article).

The Schulze method resolves votes as follows: In other words, this procedure repeatedly throws away the weakest pairwise defeat within the top set, until finally the number of votes left over produce an unambiguous decision.

Some pairwise methods—including minimax, Ranked Pairs, and the Schulze method—resolve circular ambiguities based on the relative strength of the defeats.

If all voters give complete rankings of the candidates, then winning votes and margins will always produce the same result.

There are circumstances, as in the examples above, when both instant-runoff voting and the "first-past-the-post" plurality system will fail to pick the Condorcet winner.

Condorcet methods tend to encourage the selection of centrist candidates who appeal to the median voter.

The significance of this scenario, of two parties with strong support, and the one with weak support being the Condorcet winner, may be misleading, though, as it is a common mode in plurality voting systems (see Duverger's law), but much less likely to occur in Condorcet or IRV elections, which unlike Plurality voting, punish candidates who alienate a significant block of voters.

Here is an example that is designed to support Condorcet at the expense of IRV: B would win against either A or C by more than a 65–35 margin in a one-on-one election, but IRV eliminates B first, leaving a contest between the more "polar" candidates, A and C. Proponents of plurality voting state that their system is simpler than any other and more easily understood.

Example with the Schulze method: Supporters of Condorcet methods which exhibit this potential problem could rebut this concern by pointing out that pre-election polls are most necessary with plurality voting, and that voters, armed with ranked choice voting, could lie to pre-election pollsters, making it impossible for Candidate A to know whether or how to bury.

It is also nearly impossible to predict ahead of time how many supporters of A would actually follow the instructions, and how many would be alienated by such an obvious attempt to manipulate the system.