Christian democracy in the Netherlands

Before the 1920s Catholics were treated as second class citizens and they were strongly despised by Protestants, who combined their Dutch nationalism with fierce anti-papism.

Kuyper, who had taken over leadership of the school struggle after Groen van Prinsterer's death in 1876,[2] advocated cooperation with the Catholics in order to form united opposition to the liberals, a concept known as the antithesis.

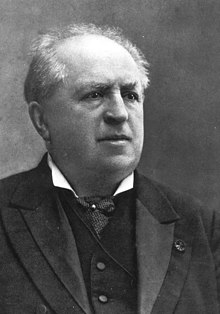

[4] The Catholics lacked a political organisation, but were informally led by Herman Schaepman, who had been the first priest elected to the States General of the Netherlands.

They lacked a shared political position, but tended to favour the extension of suffrage and equal finance for Catholic schools.

The Catholics had allied with the liberals in previous decades, but the school struggle, as well as the Quanta cura and the Syllabus of Errors of 1864, led Schaepman to move closer the Protestants instead.

[6] The Coalition returned to the opposition benches in 1891, and the new liberal government introduced a bill which would have effectively enfranchised nearly all male adults.

However, a number of Anti-Revolutionaries led by Alexander de Savornin Lohman were more reluctant to support extension of suffrage.

Firstly, De Savornin Lohman's group rejected the party discipline which Kuyper had expected of his MPs, instead valuing the independence of representatives.

De Savornin Lohman and his followers formed a separate parliamentary group after the 1894 general election, and founded the Free Anti-Revolutionary Party four years later.

[11] In 1913 a liberal cabinet was formed which sought to address all the major political issues of the time in the Pacification of 1917, which involved the extension of suffrage, the implementation of proportional representation, and equalisation of school finance.

The policy of these cabinets was characterised by conservatism: in the social sense, by strengthening pillarisation and enforcing public morality; in the economic sense, by keeping income and expenditure on the same level, which proved detrimental in the Great Depression; and in foreign policy, by adhering to armed neutrality and maintaining colonialism.

Prominent Catholic and Protestant politicians were involved in resistance work, while their political leaders were in London, where they formed a national cabinet with the liberals and the socialists.

This started a series of Roman/Red cabinets formed by the KVP and PvdA, most of which were led by social democrat Willem Drees.

The cabinets were progressive and implemented a broad range of reforms—including the formation of a welfare state, a mixed economy, decolonisation of the Dutch East Indies, and joining NATO and the European Economic Community.

In 1968 a group of left-wing, labour-oriented Catholics broke away from the KVP to form the Political Party of Radicals, and in 1971 they were joined by prominent Protestants.

They fought the 1977 elections under a single electoral list, the Christian Democratic Appeal (CDA), which became a unified party in 1980.

Ruud Lubbers, who served as prime minister from 1982 to 1984, personified the CDA's no-nonsense policies of welfare state reform and privatisation.