Magna Carta

After John's death, the regency government of his young son, Henry III, reissued the document in 1216, stripped of some of its more radical content, in an unsuccessful bid to build political support for their cause.

At the end of the war in 1217, it formed part of the peace treaty agreed at Lambeth, where the document acquired the name "Magna Carta", to distinguish it from the smaller Charter of the Forest, which was issued at the same time.

The charter became part of English political life and was typically renewed by each monarch in turn, although as time went by and the fledgling Parliament of England passed new laws, it lost some of its practical significance.

They argued that the Norman invasion of 1066 had overthrown these rights and that Magna Carta had been a popular attempt to restore them, making the charter an essential foundation for the contemporary powers of Parliament and legal principles such as habeas corpus.

Magna Carta still forms an important symbol of liberty today, often cited by politicians and campaigners, and is held in great respect by the British and American legal communities, Lord Denning describing it in 1956 as "the greatest constitutional document of all times—the foundation of the freedom of the individual against the arbitrary authority of the despot".

[7] John had lost most of his ancestral lands in France to King Philip II in 1204 and had struggled to regain them for many years, raising extensive taxes on the barons to accumulate money to fight a war which ended in expensive failure in 1214.

[10][11][12] A triumph would have strengthened his position, but in the face of his defeat, within a few months after his return from France, John found that rebel barons in the north and east of England were organising resistance to his rule.

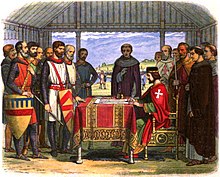

Runnymede was a traditional place for assemblies, but it was also located on neutral ground between the royal fortress of Windsor Castle and the rebel base at Staines, and offered both sides the security of a rendezvous where they were unlikely to find themselves at a military disadvantage.

[58] Meanwhile, instructions from the Pope arrived in August, written before the peace accord, with the result that papal commissioners excommunicated the rebel barons and suspended Langton from office in early September.

[72] They are listed here in the order in which they appear in the original sources: In September 1215, the papal commissioners in England—Subdeacon Pandulf, Peter des Roches, Bishop of Winchester, and Simon, Abbot of Reading—excommunicated the rebels, acting on instructions earlier received from Rome.

On his deathbed, King John appointed a council of thirteen executors to help Henry reclaim the kingdom, and requested that his son be placed into the guardianship of William Marshal, one of the most famous knights in England.

[103] As the King grew older, his government slowly began to recover from the civil war, regaining control of the counties and beginning to raise revenue once again, taking care not to overstep the terms of the charters.

[77][126] In 1258, a group of barons seized power from Henry in a coup d'état, citing the need to strictly enforce Magna Carta and the Charter of the Forest, creating a new baronial-led government to advance reform through the Provisions of Oxford.

[143] Pope Clement V continued the papal policy of supporting monarchs (who ruled by divine grace) against any claims in Magna Carta which challenged the King's rights, and annulled the Confirmatio Cartarum in 1305.

[148] In addition, medieval cases referred to the clauses in Magna Carta which dealt with specific issues such as wardship and dower, debt collection, and keeping rivers free for navigation.

[154][155][156] By the mid-15th century, Magna Carta ceased to occupy a central role in English political life, as monarchs reasserted authority and powers which had been challenged in the 100 years after Edward I's reign.

[167] The mid-sixteenth century funerary monument Sir Rowland Hill of Soulton, placed in St Stephens Wallbroke, included a full statue[168] of the Tudor statesman and judge holding a copy of Magna Carta.

[173][g] The antiquarian William Lambarde published what he believed were the Anglo-Saxon and Norman law codes, tracing the origins of the 16th-century English Parliament back to this period, but he misinterpreted the dates of many documents concerned.

[178] Antiquarians Robert Beale, James Morice and Richard Cosin argued that Magna Carta was a statement of liberty and a fundamental, supreme law empowering English government.

[182] James I and Charles I both propounded greater authority for the Crown, justified by the doctrine of the divine right of kings, and Magna Carta was cited extensively by their opponents to challenge the monarchy.

[175][182][183][184] Although the arguments based on Magna Carta were historically inaccurate, they nonetheless carried symbolic power, as the charter had immense significance during this period; antiquarians such as Sir Henry Spelman described it as "the most majestic and a sacrosanct anchor to English Liberties".

[173] His work was challenged at the time by Lord Ellesmere, and modern historians such as Ralph Turner and Claire Breay have critiqued Coke as "misconstruing" the original charter "anachronistically and uncritically", and taking a "very selective" approach to his analysis.

[189][190] The monarchy responded by arguing that the historical legal situation was much less clear-cut than was being claimed, restricted the activities of antiquarians, arrested Coke for treason, and suppressed his proposed book on Magna Carta.

[217] In 1687, William Penn published The Excellent Privilege of Liberty and Property: being the birth-right of the Free-Born Subjects of England, which contained the first copy of Magna Carta printed on American soil.

[228] Stubbs argued that Magna Carta had been a major step in the shaping of the English nation, and he believed that the barons at Runnymede in 1215 were not just representing the nobility, but the people of England as a whole, standing up to a tyrannical ruler in the form of King John.

[252] It also remains a topic of great interest to historians; Natalie Fryde characterised the charter as "one of the holiest of cows in English medieval history", with the debates over its interpretation and meaning unlikely to end.

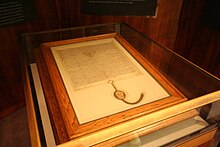

[272] The documents were written in heavily abbreviated medieval Latin in clear handwriting, using quill pens on sheets of parchment made from sheep skin, approximately 15 by 20 inches (380 by 510 mm) across.

Feudal relief was one way that a king could demand money, and clauses 2 and 3 fixed the fees payable when an heir inherited an estate or when a minor came of age and took possession of his lands.

[333] In the United States, for example, the Supreme Court of California interpreted clause 45 in 1974 as establishing a requirement in common law that a defendant faced with the potential of incarceration be entitled to a trial overseen by a legally trained judge.

[342] As described above, John had come to a compromise with Pope Innocent III in exchange for his political support for the King, and clause 1 of Magna Carta prominently displayed this arrangement, promising the freedoms and liberties of the church.