Confocal microscopy

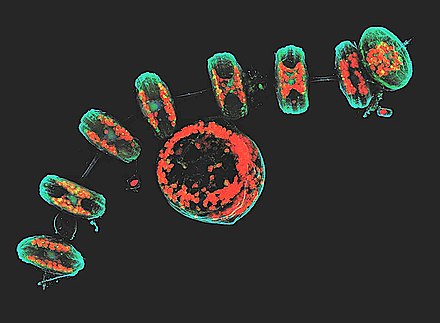

[1] Capturing multiple two-dimensional images at different depths in a sample enables the reconstruction of three-dimensional structures (a process known as optical sectioning) within an object.

The principle of confocal imaging was patented in 1957 by Marvin Minsky[2] and aims to overcome some limitations of traditional wide-field fluorescence microscopes.

As only light produced by fluorescence very close to the focal plane can be detected, the image's optical resolution, particularly in the sample depth direction, is much better than that of wide-field microscopes.

However, as much of the light from sample fluorescence is blocked at the pinhole, this increased resolution is at the cost of decreased signal intensity – so long exposures are often required.

The achievable thickness of the focal plane is defined mostly by the wavelength of the used light divided by the numerical aperture of the objective lens, but also by the optical properties of the specimen.

However, the actual dye concentration can be low to minimize the disturbance of biological systems: some instruments can track single fluorescent molecules.

Decreased excitation energy reduces phototoxicity and photobleaching of a sample often making it the preferred system for imaging live cells or organisms.

[5] Programmable array microscopes (PAM) use an electronically controlled spatial light modulator (SLM) that produces a set of moving pinholes.

Commercial spinning-disk confocal microscopes achieve frame rates of over 50 per second[6] – a desirable feature for dynamic observations such as live cell imaging.

Confocal X-ray fluorescence imaging is a newer technique that allows control over depth, in addition to horizontal and vertical aiming, for example, when analyzing buried layers in a painting.

In CLSM a specimen is illuminated by a point laser source, and each volume element is associated with a discrete scattering or fluorescence intensity.

The size of this diffraction pattern and the focal volume it defines is controlled by the numerical aperture of the system's objective lens and the wavelength of the laser used.

Increasing the intensity of illumination laser risks excessive bleaching or other damage to the specimen of interest, especially for experiments in which comparison of fluorescence brightness is required.

Such aberrations however, can be significantly reduced by mounting samples in optically transparent, non-toxic perfluorocarbons such as perfluorodecalin, which readily infiltrates tissues and has a refractive index almost identical to that of water.

The interferometric nature of the signal allows to reduce the pinhole diameter down to 0.2 Airy units and therefore enables an ideal resolution enhancement of √2 without sacrificing the signal-to-noise ratio as in confocal fluorescence microscopy.

[12] It is used for localizing and identifying the presence of filamentary fungal elements in the corneal stroma in cases of keratomycosis, enabling rapid diagnosis and thereby early institution of definitive therapy.

[16] Laser scanning confocal microscopes are used in the characterization of the surface of microstructured materials, such as Silicon wafers used in solar cell production.

Additionally deconvolution may be employed using an experimentally derived point spread function to remove the out of focus light, improving contrast in both the axial and lateral planes.

[2][24] In the 1960s, the Czechoslovak Mojmír Petráň from the Medical Faculty of the Charles University in Plzeň developed the Tandem-Scanning-Microscope, the first commercialized confocal microscope.

It was sold by a small company in Czechoslovakia and in the United States by Tracor-Northern (later Noran) and used a rotating Nipkow disk to generate multiple excitation and emission pinholes.

A first scientific publication with data and images generated with this microscope was published in the journal Science in 1967, authored by M. David Egger from Yale University and Petráň.

A second publication from 1968 described the theory and the technical details of the instrument and had Hadravský and Robert Galambos, the head of the group at Yale, as additional authors.

[28] In 1969 and 1971, M. David Egger and Paul Davidovits from Yale University, published two papers describing the first confocal laser scanning microscope.

Reflected light came back to the semitransparent mirror, the transmitted part was focused by another lens on the detection pinhole behind which a photomultiplier tube was placed.

[32][34] This CLSM design combined the laser scanning method with the 3D detection of biological objects labeled with fluorescent markers for the first time.

In 1978 and 1980, the Oxford-group around Colin Sheppard and Tony Wilson described a confocal microscope with epi-laser-illumination, stage scanning and photomultiplier tubes as detectors.

[35] Shortly after many more groups started using confocal microscopy to answer scientific questions that until then had remained a mystery due to technological limitations.

[21][36] In the mid-1980s, William Bradshaw Amos and John Graham White and colleagues working at the Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge built the first confocal beam scanning microscope.

Hugely magnified intermediate images, due to a 1–2 meter long beam path, allowed the use of a conventional iris diaphragm as a ‘pinhole’, with diameters ~1 mm.

[35] Developments at the KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm around the same time led to a commercial CLSM distributed by the Swedish company Sarastro.