Conformal map

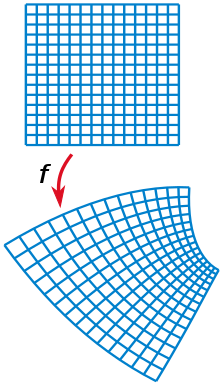

In mathematics, a conformal map is a function that locally preserves angles, but not necessarily lengths.

Conformal maps preserve both angles and the shapes of infinitesimally small figures, but not necessarily their size or curvature.

The conformal property may be described in terms of the Jacobian derivative matrix of a coordinate transformation.

The transformation is conformal whenever the Jacobian at each point is a positive scalar times a rotation matrix (orthogonal with determinant one).

Some authors define conformality to include orientation-reversing mappings whose Jacobians can be written as any scalar times any orthogonal matrix.

In three and higher dimensions, Liouville's theorem sharply limits the conformal mappings to a few types.

The notion of conformality generalizes in a natural way to maps between Riemannian or semi-Riemannian manifolds.

is antiholomorphic (conjugate to a holomorphic function), it preserves angles but reverses their orientation.

The open mapping theorem forces the inverse function (defined on the image of

[2] The Riemann mapping theorem, one of the profound results of complex analysis, states that any non-empty open simply connected proper subset of

Informally, this means that any blob can be transformed into a perfect circle by some conformal map.

The complex conjugate of a Möbius transformation preserves angles, but reverses the orientation.

The conformal maps are described by linear fractional transformations in each case.

For example, stereographic projection of a sphere onto the plane augmented with a point at infinity is a conformal map.

Any conformal map from an open subset of Euclidean space into the same Euclidean space of dimension three or greater can be composed from three types of transformations: a homothety, an isometry, and a special conformal transformation.

Conformal mappings are invaluable for solving problems in engineering and physics that can be expressed in terms of functions of a complex variable yet exhibit inconvenient geometries.

, arising from a point charge located near the corner of two conducting planes separated by a certain angle (where

In this new domain, the problem (that of calculating the electric field impressed by a point charge located near a conducting wall) is quite easy to solve.

Note that this application is not a contradiction to the fact that conformal mappings preserve angles, they do so only for points in the interior of their domain, and not at the boundary.

Another example is the application of conformal mapping technique for solving the boundary value problem of liquid sloshing in tanks.

Conformal maps are also valuable in solving nonlinear partial differential equations in some specific geometries.

Such analytic solutions provide a useful check on the accuracy of numerical simulations of the governing equation.

For example, in the case of very viscous free-surface flow around a semi-infinite wall, the domain can be mapped to a half-plane in which the solution is one-dimensional and straightforward to calculate.

[20] For discrete systems, Noury and Yang presented a way to convert discrete systems root locus into continuous root locus through a well-know conformal mapping in geometry (aka inversion mapping).

[21] Maxwell's equations are preserved by Lorentz transformations which form a group including circular and hyperbolic rotations.

A larger group of conformal maps for relating solutions of Maxwell's equations was identified by Ebenezer Cunningham (1908) and Harry Bateman (1910).

As recounted by Andrew Warwick (2003) Masters of Theory: [22] Warwick highlights this "new theorem of relativity" as a Cambridge response to Einstein, and as founded on exercises using the method of inversion, such as found in James Hopwood Jeans textbook Mathematical Theory of Electricity and Magnetism.

In general relativity, conformal maps are the simplest and thus most common type of causal transformations.

Physically, these describe different universes in which all the same events and interactions are still (causally) possible, but a new additional force is necessary to affect this (that is, replication of all the same trajectories would necessitate departures from geodesic motion because the metric tensor is different).

It is often used to try to make models amenable to extension beyond curvature singularities, for example to permit description of the universe even before the Big Bang.