Conodont

Conodonts (Greek kōnos, "cone", + odont, "tooth") are an extinct group of jawless vertebrates, classified in the class Conodonta.

They are primarily known from their hard, mineralised tooth-like structures called "conodont elements" that in life were present in the oral cavity and used to process food.

Conodont elements are highly distinctive to particular species and are widely used in biostratigraphy as indicative of particular periods of geological time.

The teeth-like fossils of the conodont were first discovered by Heinz Christian Pander and the results published in Saint Petersburg, Russia, in 1856.

In the 1990s exquisite fossils were found in South Africa in which the soft tissue had been converted to clay, preserving even muscle fibres.

The original German term used by Pander was "conodonten", which was subsequently anglicized as "conodonts", though no formal latinized name was provided for several decades.

[1] A few other scientific names were rarely and inconsistently applied to conodonts and their proposed close relatives during 20th century, such as Conodontophoridia, Conodontophora, Conodontochordata, Conodontiformes,[5] and Conodontomorpha.

Conodonta and Conodontophorida are by far the most common scientific names used to refer to conodonts, though inconsistencies regarding their taxonomic rank still persist.

[6] This approach was criticized by Fåhraeus (1983), who argued that it overlooked Pander's historical relevance as a founder and primary figure in conodontology.

[12] By closely observing these rare specimens, Briggs et al. (1983)[13] were able to for the first time study the anatomy of the complexes formed by the conodont elements arranged as they were in life.

For many years, conodonts were known only from enigmatic tooth-like microfossils (200 micrometers to 5 millimeters in length[17]), which occur commonly, but not always, in isolation and were not associated with any other fossil.

The conodont apparatus may comprise a number of discrete elements, including the spathognathiform, ozarkodiniform, trichonodelliform, neoprioniodiform, and other forms.

These conodont elements are arranged towards the animal's anterior oral surface, forming an interlocking basket of cusps within the mouth.

M (makellate) elements have a higher position in the mouth and commonly form a symmetrical shape akin to a horseshoe or pick.

Modern hagfish and lampreys scrape at flesh using keratinous blades supported by a simple but effective pulley-like system, involving a string of muscles around a cartilaginous core.

The blade-like P elements deeper in the throat would process the food by slicing against their counterparts like a pair of scissors,[16] or grinding against each other like molar teeth.

Studies have concluded that conodonts taxa occupied both pelagic (open ocean) and nektobenthic (swimming above the sediment surface) niches.

[40] Milsom and Rigby envision them as vertebrates similar in appearance to modern hagfish and lampreys,[41] and phylogenetic analysis suggests they are more derived than either of these groups.

[9] However, this analysis comes with one caveat: the earliest conodont-like fossils, the protoconodonts, appear to form a distinct clade from the later paraconodonts and euconodonts.

Protoconodonts are probably not relatives of true conodonts, but likely represent a stem group to Chaetognatha, an unrelated phylum that includes arrow worms.

The following is a simplified cladogram based on Sweet and Donoghue (2001),[10] which summarized previous work by Sweet (1988)[8] and Donoghue et al. (2000):[9] Paraconodontida Cavidonti / Proconodontida Protopanderodontida Panderontida Paracordylodus Balognathidae Prioniodinida Ozarkodinida Only a few studies approach the question of conodont ingroup relationships from a cladistic perspective, as informed by phylogenetic analyses.

[46][47] Only a handful of conodont genera were present during the Permian, though diversity increased after the P-T extinction during the Early Triassic.

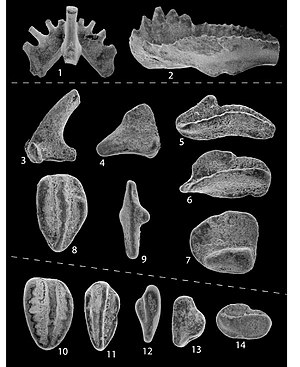

1. Kladognathus sp. , Sa element, posterior view, X140 2. Cavusgnathus unicornis , gamma morphotype, Pa element, lateral view, X140

3–9. Conodonts from the uppermost Loyalhanna Limestone Member of the Mauch Chunk Formation, Keystone quarry, Pa. This collection (93RS–79b) is from the upper 10 cm of the Loyalhanna Member. Note the highly abraded and reworked aeolian forms.

3, 4. Kladognathus sp. , Sa element, lateral views, X140

5. Cavusgnathus unicornis , alpha morphotype, Pa element, lateral view, X140

6, 7. Cavusgnathus sp. , Pa element, lateral view, X140

8. Polygnathus sp. , Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, X140

9. Gnathodus texanus? , Pa element, upper view, X140

10–14. Conodonts from the basal 20 cm of the Loyalhanna Limestone Member of the Mauch Chunk Formation, Keystone quarry, Pa. (93RS–79a), and Westernport, Md. (93RS–67), note the highly abraded and reworked aeolian forms

10. Polygnathus sp. , Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–79a, X140

11. Polygnathus sp. , Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian to Early Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–67, X140

12. Gnathodus sp. , Pa element, upper view, reworked Late Devonian(?) through Mississippian morphotype, 93RS–67, X140

13. Kladognathus sp. , M element, lateral views, 93RS–67, X140

14. Cavusgnathus sp. , Pa element, lateral view, 93RS–67, X140