Conservative Revolution

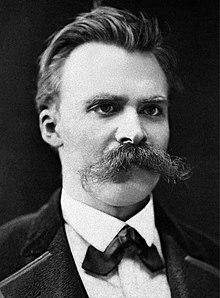

Plunged into what historian Fritz Stern has named a deep "cultural despair", uprooted as they felt within the rationalism and scientism of the modern world, theorists of the Conservative Revolution drew inspiration from various elements of the 19th century, including Friedrich Nietzsche's contempt for Christian ethics, democracy and egalitarianism; the anti-modern and anti-rationalist tendencies of German Romanticism; the vision of an organic and naturally-organized folk community cultivated by the Völkisch movement; the Prussian tradition of militaristic and authoritarian nationalism; and their own experience of comradeship and irrational violence on the front lines of World War I.

[16] Molher's post-war ideological reconstruction of the "Conservative Revolution" has been widely criticized by scholars, but the validity of a redefined concept of "neo-conservative"[6] or "new nationalist" movement active during the Weimar period (1918–1933),[2] whose lifetime is sometimes extended to the years 1890s–1910s,[17] and which differed in particular from the "old nationalism" of the 19th century, is now generally accepted in scholarship.

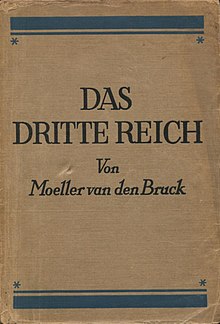

[19] Despite the apparent contradiction, however, the association of the terms "Conservative" and "Revolution" is justified in Moeller van den Bruck's writings by his definition of the movement as a will to preserve eternal values while favouring at the same time the redesign of ideal and institutional forms in response to the "insecurities of the modern world".

This change of attitude, compared to 19th-century conservatism, is described as a Bejahung ("affirmation") by Dupeux: Conservative Revolutionaries said "yes" to their time as long as they could find the ways to facilitate the resurgence of anti-liberal and what they saw as "eternal values" within modern societies.

Yet this change of Haltung ("attitude") had significant consequences — the backward-looking regret is replaced by a juvenile energy — and led to a wide-ranging political and cultural initiative.Political scientist Tamir Bar-On has defined the Conservative Revolution as a combination of "German ultra-nationalism, defence of the organic folk community, technological modernity, and socialist revisionism, which perceived the worker and soldier as models for a reborn authoritarian state superseding the egalitarian "decadence" of liberalism, socialism, and traditional conservatism.

"[15] Historian Fritz Stern described the movement as disoriented intellectuals plunged into a profound "cultural despair": they felt alienated and uprooted within a world dominated by what they saw as "bourgeois rationalism and science".

[32] Ernst Jünger is the major figure of that branch of the Conservative Revolution which wanted to uphold military structures and values in peacetime society, and saw in the community of front line comradeship (Frontgemeinschaft) the true nature of German socialism.

In the face of modernity as an era of insecurity, opposing the securities of the past is no longer enough; instead it is necessary to redesign new safety by adopting and taking on the same risky conditions with which it is defined.Edgar Jung indeed dismissed the idea that true conservatives wanted to "stop the wheel of history".

[15] Let thousands, nay millions, die; what meaning have these rivers of blood in comparison with a state, into which flow all the disquiet and longing of the German being!Völkischen were involved in a racialist and occultist movement dating back to the middle of the 19th century and had an influence on the Conservative Revolution.

Comparing what he saw as the effective and ineffective elements of the new constitution, he highlighted the office of the Reichspräsident as a valuable position, essentially due to the power granted to the president by the Article 48 to declare an Ausnahmezustand ("state of emergency"), which Schmitt implicitly praised as dictatorial.

Another source of aversion for capitalism was rooted in the profits made from the war and inflation, and a last concern can be found in the fact that most of Conservative Revolutionaries belonged to the middle class, in which they felt crushed at the centre of an economic struggle between the ruling capitalists and the potentially dangerous masses.

Spengler also wrote about the decline of the West as an ineluctable phenomenon, but his intention was to provide modern readers with a "new socialism" that would enable them to realize the meaninglessness of life, contrasting with Marx's idea of the coming of paradise on earth.

We feel that it is life which dominates reason.Along with Karl Otto Paetel and Heinrich Laufenberg, Ernst Niekisch was one of the main advocates of National Bolshevism,[88] a minor branch of the Conservative Revolution described as the "left-wing-people of the right" (Linke Leute von rechts).

[89] They defended an ultra-nationalist form of socialism that took its roots in both Völkisch extremism and nihilistic Kulturpessimismus, rejecting any Western influence on German society: liberalism and democracy, capitalism and Marxism, the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, Christianity and humanism.

A third division split the supporters of deep and lengthy political and cultural transformations from those who endorsed a quick and erupting social revolution, as far as challenging economic freedom and private property.

The fourth rift resided in the question of the Drang nach Osten ("drive to the East") and the attitude to adopt towards Bolshevik Russia, escorted by a debate on the place of Germany between a so-called "senile" West and "young and barbaric" Orient; the last division being a deep opposition between the Völkischen and the pre-fascist thinkers.

[3] In 1995, historian Rolf Peter Sieferle described what he labelled five "complexes" in the Conservative Revolution: the "völkischen", the "national socialists", the "revolutionary nationalists" as such, the "vital-activists" (aktivistisch-vitalen), and, a minority in the movement, the "biological naturalists".

Among them was Edgar Jung, who advocated the creation of a corporatist organic state, free from class struggle and parliamentary democracy, which would make way for a return to the spirit of the Middle Ages with a new Holy Roman Empire federating central Europe.

[...] The apparatus itself deserved no admiration — that was the dangerous thing to do — it just had to be used.Jünger supported the emergence of a young intellectual elite that would spring out from the trenches of WWI, ready to oppose bourgeois capitalism and to embody a new nationalist revolutionary spirit.

But while they used terms like Nordische Rasse ("Nordic race") and Germanentum ("Germanic peoples"), their concept of Volk could also be more flexible and understood as a Gemeinsame Sprache ("common language"),[109] or as an Ausdruck einer Landschaftsseele ("expression of a landscape's soul") in the words of geographer Ewald Banse.

[116] Their anti-democratic and militaristic thoughts certainly participated in making the idea of an authoritarian regime acceptable to the semi-educated middle-class, and even to the educated youth,[7] but Conservative Revolutionary writings did not have a decisive influence on National Socialist ideology.

The Germanic critics did all that, thereby demonstrating the terrible dangers of the politics of cultural despair.Many Conservative Revolutionaries, while keeping on opposing liberalism and still adhering to the notion of a "strong leader",[25] rejected the totalitarian or the antisemitic nature of the Nazi regime.

If we had said back then, it is not right when Hermann Göring simply puts 100,000 Communists in the concentration camps, in order to let them die.Rudolf Pechel and Fiedrich Hielscher openly opposed the Nazi regime, while Thomas Mann went into exile in 1939 and broadcast anti-Nazi speeches to the German people via the BBC during the war.

Edgar Jung, a leading figure of the Conservative Revolution, was murdered during the Night of the Long Knives by the SS of Heinrich Himmler, who wanted to prevent competitive nationalist ideas from opposing or deviating from Hitler's doctrine.

[129] Ernst Niekisch, although anti-Jewish and in favour of a totalitarian state, rejected Adolf Hitler as he felt he lacked any real socialism, and instead found in Joseph Stalin his model for the Führer Principle.

Mohler called Conservative Revolutionaries the "Trotskyites of the German Revolution", and his appropriation of the concept has been recurrently accused of being a biased attempt to reconstruct a pre-WWII far-right movement acceptable in a post-fascist Europe, by downplaying the influence some of these thinkers had on the rise of Nazism.

[146] In 1996, British historian Roger Woods recognized the validity of the concept, while stressing the eclectic character of the movement and their inability to form a common agenda, a political deadlock he labelled the "conservative dilemma".

[147] Regarding the ambiguous relationship with Nazism, downplayed by Mohler in his 1949 thesis and accentuated by 1970s analysts, Woods argued that "regardless of individual Conservative Revolutionary criticisms of the Nazis, the deeper commitment to activism, strong leadership, hierarchy and a disregard for political programmes persists.

[148] Landa points out that Oswald Spenger's "Prussian Socialism" strongly opposed labor strikes, trade unions, progressive taxation or any imposition of taxes on the rich, any shortening of the working day, as well as any form of government insurance for sickness, old age, accidents, or unemployment.

"[148] Landa likewise describes Arthur Moeller van den Bruck as a "socialist champion of capitalism" who praised free trade, flourishing markets, the creative value of the entrepreneur, and the capitalist division of labor, and sought to emulate British and French imperialism.