Constantine III (Western Roman emperor)

He promptly moved to Gaul (modern France), taking all of the mobile troops from Britain, with their commander Gerontius, to confront bands of Germanic invaders who had crossed the Rhine the previous winter.

The sitting emperor of the Western Roman Empire, Honorius, sent an army under Sarus the Goth to expel Constantine's forces.

[1] Honorius was underage and the leading general Stilicho became hugely influential and the de facto commander-in-chief of the Roman armies in the west.

[5] Other interpretations suggest it went badly, or that troops defending Roman Britain defeated a Pictish invasion without external support.

[5][9][10] The year 402 is the last date from which Roman coinage is found in large quantities in Britain, suggesting the Empire was no longer paying the troops who remained.

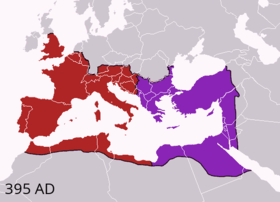

[11] Both the Eastern and Western Empires were suffering from incursions of large groups from Germanic tribes, whom the Romans referred to generically as "barbarians".

After concentrating his forces, Stilicho caught the Goths while they were besieging Florentia (modern Florence) and defeated them at the Battle of Faesulae; 12,000 prisoners joined the Roman army and so many captives were sold that the market in slaves collapsed.

[note 2][21][22] Hearing of the Germanic invasion the Roman military in Britain was desperate for some sense of security in a world that seemed to be rapidly falling apart.

They next chose as their leader a man named after the famed emperor of the early fourth century, Constantine the Great, who had himself risen to power through a military coup in Britain.

[23][24][25] The modern historian Francisco Sanz-Huesma differs and proposes that Constantine was a skilled politician who engineered the three acclamations with the (successful) intention of eventually raising himself to imperial power.

[29] Constantine moved quickly: he appointed two officers already in Gaul (modern France) as generals, Justinianus and Nebiogastes, instructing them to seize Arles and the passes which controlled traffic to and from Italy.

He crossed the Channel at Bononia (modern Boulogne), taking with him all of the 6,000 or so mobile troops left in Britain and their commander, the general Gerontius.

Sending a large Western Roman force to the east would have left Italy open to invasion by one or both of these groups and so the offensive was cancelled.

[41][42] Another army, led by Gerontius and Edobichus and largely made up of freshly recruited Franks and Almannics, arrived to relieve Valence after a week of siege.

[44] By May 408 Constantine had captured Arles and made it his capital,[45] taking over the existing imperial administration and officials, and appointing Apollinaris as chief minister (with the title of praetorian prefect).

[note 3][48] Constantine commenced minting large quantities of good quality coins at Arles, possibly using bullion seized from Sarus's loot during his hasty retreat, and made a show of being an equal of both the Western and Eastern Emperors.

[43] Constantine's oldest son had entered a monastery and was a monk at the time his father rebelled, but he was summoned to the new imperial court.

[30][43] Hispania was a stronghold of the House of Theodosius,[45] but, on Constantine's initial landing on the continent, Honorius's relatives and partisans there had been either unwilling or militarily unable to oppose his assumption of control.

When Sarus withdrew to Italy, the knowledge of the large new army assembling at Ticinum (modern Pavia) with the intention of shortly engaging Constantine encouraged them to persist and even to attempt to seal the Pyrenean passes.

The Roman establishment, led by the senior bureaucrat Olympius, worked to oppose Stilicho by spreading rumours that he wished to travel east to depose Theodosius and set his own son on the throne.

[56] Olympius reversed the policy of making a massive payment to the Visigoths and the native parts of the Army of Italy started slaughtering Goths, especially their fellow soldiers and their wives and children.

[58][59][60] With the Visigoths deep in Italy and unopposed, Olympius's influence ended[note 4] and a new chief minister, Jovius, entered into peace negotiations[62] but Honorius continued to refuse to reach an agreement with Alaric.

Concentrating on the threat from Constans, Gerontius weakened his garrisons in the Pyrenean passes and in autumn 409 much of the barbarian force entered Hispania.

[65][66] Eventually Gerontius was able to reach a modus operandi with some of these groups whereby they supplied him with military forces, which enabled him to take the offensive against Constantine.

[66] From 408 Saxon pirates raided Roman Britain extensively, undeterred by the totally inadequate force which Constantine had left.

[69] Distressed that Constantine had failed to defend them, the Roman inhabitants of Britain rebelled and expelled his officials,[50][60][70] accepting that henceforth they would have to look to their own defence.

[19] Inspired by the example of Roman Britain, later that year the Bagaudae of Armorica (modern Brittany) also expelled Constantine's officials and declared independence.

[77] Constantine, his hopes fading after the troops guarding the Rhine abandoned him to support yet another claimant to the imperial throne, the Gallo-Roman Jovinus, surrendered to Constantius along with his surviving son Julian.

[78] Despite a promise of safe passage, and Constantine's assumption of clerical office, Constantius imprisoned the former soldier and had him and Julian beheaded in either August or September 411.

He has been associated with the Constantine found in Geoffrey of Monmouth's popular and imaginative Historia Regum Britanniae, who comes to power following Gracianus Municeps's reign.