Constitution

[8] The term constitution comes through French from the Latin word constitutio, used for regulations and orders, such as the imperial enactments (constitutiones principis: edicta, mandata, decreta, rescripta).

William Blackstone used the term for significant and egregious violations of public trust, of a nature and extent that the transgression would justify a revolutionary response.

According to Scott Gordon, a political organization is constitutional to the extent that it "contain[s] institutionalized mechanisms of power control for the protection of the interests and liberties of the citizenry, including those that may be in the minority".

Sometimes the problem is not that a statute is unconstitutional, but that the application of it is, on a particular occasion, and a court may decide that while there are ways it could be applied that are constitutional, that instance was not allowed or legitimate.

[14] In the late 18th century, Thomas Jefferson predicted that a period of 20 years would be the optimal time for any constitution to be still in force, since "the earth belongs to the living, and not to the dead".

[14] By contrast, some constitutions, notably that of the United States, have remained in force for several centuries, often without major revision for long periods of time.

The most common reasons for these frequent changes are the political desire for an immediate outcome[clarification needed] and the short time devoted to the constitutional drafting process.

In North Korea, for example, the Ten Principles for the Establishment of a Monolithic Ideological System are said to have eclipsed the constitution in importance as a frame of government in practice.

Excavations in modern-day Iraq by Ernest de Sarzec in 1877 found evidence of the earliest known code of justice, issued by the Sumerian king Urukagina of Lagash c. 2300 BC.

In 621 BC, a scribe named Draco codified the oral laws of the city-state of Athens; this code prescribed the death penalty for many offenses (thus creating the modern term "draconian" for very strict rules).

Many of the Germanic peoples that filled the power vacuum left by the Western Roman Empire in the Early Middle Ages codified their laws.

This was followed by the Lex Burgundionum, applying separate codes for Germans and for Romans; the Pactus Alamannorum; and the Salic Law of the Franks, all written soon after 500.

In 506, the Breviarum or "Lex Romana" of Alaric II, king of the Visigoths, adopted and consolidated the Codex Theodosianus together with assorted earlier Roman laws.

[22][23] The document was drawn up with the explicit concern of bringing to an end the bitter intertribal fighting between the clans of the Aws (Aus) and Khazraj within Medina.

The most important single article of Magna Carta, related to "habeas corpus", provided that the king was not permitted to imprison, outlaw, exile or kill anyone at a whim – there must be due process of law first.

These Constitutions were usually made formally as a royal initiative, but required for its approval or repeal the favorable vote of the Catalan Courts, the medieval antecedent of the modern Parliaments.

[31][32]: 334 The Golden Bull of 1356 was a decree issued by a Reichstag in Nuremberg headed by Emperor Charles IV that fixed, for a period of more than four hundred years, an important aspect of the constitutional structure of the Holy Roman Empire.

Written in 1600, the document was based upon the Statuti Comunali (Town Statute) of 1300, itself influenced by the Codex Justinianus, and it remains in force today.

[37] Drafted by Major-General John Lambert in 1653, the Instrument of Government included elements incorporated from an earlier document "Heads of Proposals",[38][39] which had been agreed to by the Army Council in 1647, as a set of propositions intended to be a basis for a constitutional settlement after King Charles I was defeated in the First English Civil War.

The constitution set up a state council consisting of 21 members while executive authority was vested in the office of "Lord Protector of the Commonwealth."

The Instrument of Government was replaced in May 1657 by England's second, and last, codified constitution, the Humble Petition and Advice, proposed by Sir Christopher Packe.

It is notable in that it established a democratic standard for the separation of powers in government between the legislative, executive, and judiciary branches, well before the publication of Montesquieu's Spirit of the Laws.

This Constitution also limited the executive authority of the hetman, and established a democratically elected Cossack parliament called the General Council.

The king also cherished other enlightenment ideas (as an enlighted despot) and repealed torture, liberated agricultural trade, diminished the use of the death penalty and instituted a form of religious freedom.

[46][47][48] Its draft was developed by the leading minds of the Enlightenment in Poland such as King Stanislaw August Poniatowski, Stanisław Staszic, Scipione Piattoli, Julian Ursyn Niemcewicz, Ignacy Potocki and Hugo Kołłątaj.

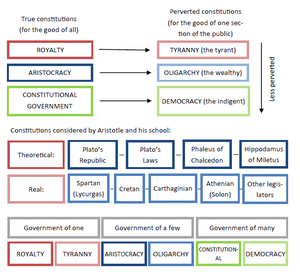

[56][57] After tribal people first began to live in cities and establish nations, many of these functioned according to unwritten customs, while some developed autocratic, even tyrannical monarchs, who ruled by decree, or mere personal whim.

The Renaissance brought a series of political philosophers who wrote implied criticisms of the practices of monarchs and sought to identify principles of constitutional design that would be likely to yield more effective and just governance from their viewpoints.

[61] A seminal juncture in this line of discourse arose in England from the Civil War, the Cromwellian Protectorate, the writings of Thomas Hobbes, Samuel Rutherford, the Levellers, John Milton, and James Harrington, leading to the debate between Robert Filmer, arguing for the divine right of monarchs, on the one side, and on the other, Henry Neville, James Tyrrell, Algernon Sidney, and John Locke.

Provisions that conflict with what Brownson and others can discern are the underlying "constitutions" of nature and society tend to be difficult or impossible to execute, or to lead to unresolvable disputes.

[76] The Constitution of Colombia also lacks explicit entrenched clauses, but has a similar substantive limit on amending its fundamental principles through judicial interpretations.