Constructivist architecture

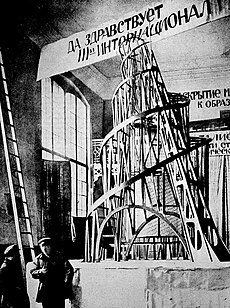

Though it remained unbuilt, the materials—glass and steel—and its futuristic ethos and political slant (the movements of its internal volumes were meant to symbolise revolution and the dialectic) set the tone for the projects of the 1920s.

The teaching methods were both functional and fantastic, reflecting an interest in Gestalt psychology, leading to daring experiments with form such as Simbirchev's glass-clad suspended restaurant.

[5] Another glimpse of a Constructivist lived environment is visible in the popular science fiction film Aelita, which had interiors and exteriors modelled in angular, geometric fashion by Aleksandra Ekster.

[8] This was built in 1926–7 and designed by Grigori Barkhin[9] A colder and more technological Constructivist style was introduced by the 1923/4 glass office project by the Vesnin brothers for Leningradskaya Pravda.

A particularly extravagant example is the 'Chekists Village' in Sverdlovsk (now Yekaterinburg) designed by Ivan Antonov, Veniamin Sokolov and Arseny Tumbasov, a hammer and sickle shaped collective housing complex for staff of the People's Commissariat for the Internal Affairs (NKVD), which currently serves as a hotel.

The popularity of the new aesthetic led to traditionalist architects adopting Constructivism, as in Ivan Zholtovsky's 1926 MOGES power station or Alexey Shchusev's Narkomzem offices, both in Moscow.

[5] Many of these buildings are shown in Sergei Eisenstein's film The General Line, which also featured a specially built mock-up Constructivist collective farm designed by Andrey Burov.

At the same time as this foray into the everyday, outlandish projects were designed such as Ivan Leonidov's Lenin Institute, a high tech work that bears comparison with Buckminster Fuller.

This consisted of a skyscraper-sized library, a planetarium and dome, all linked together by a monorail; or Georgy Krutikov's self-explanatory Flying City, an ASNOVA project that was intended as a serious proposal for airborne housing.

There were also projects for Suprematist skyscrapers called 'planits' or 'architektons' by Kasimir Malevich, Lazar Khikeidel – Cosmic Habitats (1921–1922), Architectons (1922–1927), Workers Club (1926), Communal Dwelling (Коммунальное Жилище)(1927), A. Nikolsky and L. Khidekel – Moscow Cooperative Institute (1929).

The fantastical element also found expression in the work of Yakov Chernikhov, who produced several books of experimental designs—most famously Architectural Fantasies (1933)—earning him the epithet 'the Soviet Piranesi'.

His disurbanism proposed a system of one-person or one-family buildings connected by linear transport networks, spread over a huge area that traversed the boundaries between the urban and agricultural, in which it resembled a socialist equivalent of Frank Lloyd Wright's Broadacre City.

The city-planning of Le Corbusier found brief favour, with the architect writing a 'reply to Moscow' that later became the Ville Radieuse plan, and designing the Tsentrosoyuz government building with the Constructivist Nikolai Kolli.

Another famous modernist, Erich Mendelsohn, designed Leningrad's Red Banner Textile Factory and popularised Constructivism in his book Russland, Europa, Amerika.

A Five Year Plan project with major Constructivist input was DniproHES, designed by Victor Vesnin et al. El Lissitzky also popularised the style abroad with his 1930 book The Reconstruction of Architecture in Russia.

The 1932 competition for the Palace of the Soviets, a grandiose project to rival the Empire State Building, featured entries from all the major Constructivists as well as Walter Gropius, Erich Mendelsohn and Le Corbusier.

Housing projects like the Narkomfin were designed for the attempts to reform everyday life in the 1920s, such as collectivisation of facilities, equality of the sexes and collective raising of children, all of which fell out of favour as Stalinism revived family values.

Traces of Constructivism can also be found in some Socialist Realist works, for instance in the Futurist elevations of Iofan's ultra-Stalinist 1937 Paris Pavilion, which had Suprematist interiors by Nikolai Suetin.