Convex cone

In linear algebra, a cone—sometimes called a linear cone for distinguishing it from other sorts of cones—is a subset of a real vector space that is closed under positive scalar multiplication; that is,

This is a broad generalization of the standard cone in Euclidean space.

A convex cone is a cone that is also closed under addition, or, equivalently, a subset of a vector space that is closed under linear combinations with positive coefficients.

This concept is meaningful for any vector space that allows the concept of "positive" scalar, such as spaces over the rational, algebraic, or (more commonly) the real numbers.

Also note that the scalars in the definition are positive meaning that the origin does not have to belong to

Some authors use a definition that ensures the origin belongs to

[10] A common example is translating a convex cone by a point p: p + C. Technically, such transformations can produce non-cones.

where f is a linear functional on the vector space V. A closed half-space is a set in the form

and likewise an open half-space uses strict inequality.

[11][12] Half-spaces (open or closed) are affine convex cones.

Moreover (in finite dimensions), any convex cone C that is not the whole space V must be contained in some closed half-space H of V; this is a special case of Farkas' lemma.

[14] Every polyhedral cone has a unique representation as a conical hull of its extremal generators, and a unique representation of intersections of halfspaces, given each linear form associated with the halfspaces also define a support hyperplane of a facet.

[18] Each face of a polyhedral cone is spanned by some subset of its extremal generators.

Polyhedral cones play a central role in the representation theory of polyhedra.

For instance, the decomposition theorem for polyhedra states that every polyhedron can be written as the Minkowski sum of a convex polytope and a polyhedral cone.

[19][21][22] The two representations of a polyhedral cone - by inequalities and by vectors - may have very different sizes.

[13]: 256 The two representations together provide an efficient way to decide whether a given vector is in the cone: to show that it is in the cone, it is sufficient to present it as a conic combination of the defining vectors; to show that it is not in the cone, it is sufficient to present a single defining inequality that it violates.

Fortunately, Carathéodory's theorem guarantees that every vector in the cone can be represented by at most

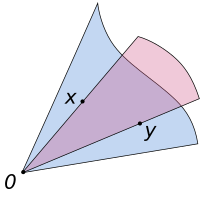

A cone is called flat if it contains some nonzero vector x and its opposite −x, meaning C contains a linear subspace of dimension at least one, and salient (or strictly convex) otherwise.

[28] The term "pointed" is also often used to refer to a closed cone that contains no complete line (i.e., no nontrivial subspace of the ambient vector space V, or what is called a salient cone).

[29][30][31] The term proper (convex) cone is variously defined, depending on the context and author.

It often means a cone that satisfies other properties like being convex, closed, pointed, salient, and full-dimensional.

"Rational cones are important objects in toric algebraic geometry, combinatorial commutative algebra, geometric combinatorics, integer programming.".

A cone is called rational (here we assume "pointed", as defined above) whenever its generators all have integer coordinates, i.e., if

More generally, the (algebraic) dual cone to C ⊂ V in a linear space V is a subset of the dual space V* defined by: In other words, if V* is the algebraic dual space of V, C* is the set of linear functionals that are nonnegative on the primal cone C. If we take V* to be the continuous dual space then it is the set of continuous linear functionals nonnegative on C.[36] This notion does not require the specification of an inner product on V. In finite dimensions, the two notions of dual cone are essentially the same because every finite dimensional linear functional is continuous,[37] and every continuous linear functional in an inner product space induces a linear isomorphism (nonsingular linear map) from V* to V, and this isomorphism will take the dual cone given by the second definition, in V*, onto the one given by the first definition; see the Riesz representation theorem.

Both the normal and tangent cone have the property of being closed and convex.

They are important concepts in the fields of convex optimization, variational inequalities and projected dynamical systems.

[38] A pointed and salient convex cone C induces a partial ordering "≥" on V, defined so that

Examples include the product order on real-valued vectors,

and the Loewner order on positive semidefinite matrices.