Convexity in economics

Empirical methods Prescriptive and policy Convexity is a geometric property with a variety of applications in economics.

[1] Informally, an economic phenomenon is convex when "intermediates (or combinations) are better than extremes".

Convexity is a key simplifying assumption in many economic models, as it leads to market behavior that is easy to understand and which has desirable properties.

For example, the Arrow–Debreu model of general economic equilibrium posits that if preferences are convex and there is perfect competition, then aggregate supplies will equal aggregate demands for every commodity in the economy.

The branch of mathematics which supplies the tools for convex functions and their properties is called convex analysis; non-convex phenomena are studied under nonsmooth analysis.

The economics depends upon the following definitions and results from convex geometry.

A real vector space of two dimensions may be given a Cartesian coordinate system in which every point is identified by a list of two real numbers, called "coordinates", which are conventionally denoted by x and y.

, vD) } together with two operations: vector addition and multiplication by a real number.

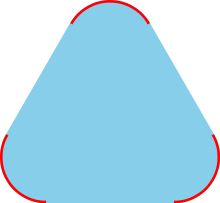

For example, a solid cube is convex; however, anything that is hollow or dented, for example, a crescent shape, is non‑convex.

+ λDvD, for some indexed set of non‑negative real numbers {λd} satisfying the equation λ0 + λ1 + .

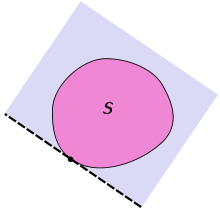

An optimal basket of goods occurs where the consumer's convex preference set is supported by the budget constraint, as shown in the diagram.

(The meanings of "closed set" is explained below, in the subsection on optimization applications.)

If a preference set is non‑convex, then some prices produce a budget supporting two different optimal consumption decisions.

[11] Concerns with large producers exploiting market power in fact initiated the literature on non‑convex sets, when Piero Sraffa wrote about on firms with increasing returns to scale in 1926,[12] after which Harold Hotelling wrote about marginal cost pricing in 1938.

[13] Both Sraffa and Hotelling illuminated the market power of producers without competitors, clearly stimulating a literature on the supply-side of the economy.

"Non‑convexities in [both] production and consumption ... required mathematical tools that went beyond convexity, and further development had to await the invention of non‑smooth calculus" (for example, Francis Clarke's locally Lipschitz calculus), as described by Rockafellar & Wets (1998)[21] and Mordukhovich (2006),[22] according to Khan (2008).

According to Brown (1991, p. 1966), "Non‑smooth analysis extends the local approximation of manifolds by tangent planes [and extends] the analogous approximation of convex sets by tangent cones to sets" that can be non‑smooth or non‑convex.