Convicts in Australia

After trans-Atlantic transportation ended with the start of the American Revolution, authorities sought an alternative destination to relieve further overcrowding of British prisons and hulks.

[2] Western Australia – established as the Swan River Colony in 1829 – initially was intended solely for free settlers, but commenced receiving convicts in 1850.

[7] The convict era has inspired famous novels, films, and other cultural works, and the extent to which it has shaped Australia's national character has been studied by many writers and historians.

[8] According to Robert Hughes in The Fatal Shore, the population of England and Wales, which had remained steady at 6 million from 1700 to 1740, began rising considerably after 1740.

[9] Poverty, social injustice, child labour, harsh and dirty living conditions and long working hours were prevalent in 19th-century Britain.

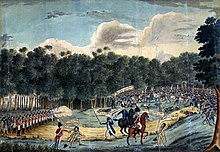

On 18 August 1786, the decision was made to send a colonisation party of convicts, military, and civilian personnel to Botany Bay under the command of Captain Arthur Phillip, who was appointed as Governor of the new colony.

The different coves of this harbour were examined with all possible expedition, and the preference was given to one which had the finest spring of water, and in which ships can anchor so close to the shore, that at a very small expence quays may be constructed at which the largest vessels may unload.

Furious magistrates and employers petitioned the crown against this interference with their legal rights, fearing that a reduction in punishments would cease to provide enough deterrence to the convicts.

It has been argued that the suspension of convict transportation to New South Wales in 1840[18] can be attributed to the actions of Bourke and other like-minded men, such as Australian-born lawyer William Charles Wentworth.

The Macquarie Harbour penal colony on the West Coast of Tasmania was established in 1820 to exploit the valuable timber Huon Pine growing there for furniture making and shipbuilding.

Several hundred non-indigenous black convicts were transported to Van Diemen's Land, most as punishment for speaking or acting against the British Empire.

Many changes were made to the manner in which convicts were handled in the general population, largely responsive to British public opinion on the harshness of their treatment.

From the early 1840s the Probation System was employed, where convicts spent an initial period, usually two years, in public works gangs on stations outside of the main settlements.

Records on the individual convicts transported to Van Diemen’s Land or born there between 1803 and 1900 were being digitised as of 2019[update] as part of the Founders and Survivors project.

One such convict, the subsequently celebrated William Buckley, lived in the western side of Port Phillip for the next 32 years before approaching the new settlers and assisting as an interpreter for the indigenous peoples.

[23] The Port Phillip District was officially sanctioned in 1837 following the landing of the Henty brothers in Portland Bay in 1834, and John Batman settled on the site of Melbourne.

Fears that France would lay claim to the land prompted the Governor of New South Wales, Ralph Darling, to send Major Edmund Lockyer, with troops and 23 convicts, to establish a settlement at King George Sound.

Convicts also crewed the pilot boat, rebuilt York Street and Stirling Terrace; and the track from Albany to Perth was made into a good road.

[27][28] With increasing numbers of free settlers entering New South Wales and Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania) by the mid-1830s, opposition to the transportation of felons into the colonies grew.

The anti-transportation movement was seldom concerned with the inhumanity of the system, but rather the "hated stain" it was believed to inflict on the free (non-emancipist) middle classes.

The sending of convicts to Brisbane in its Moreton Bay district had ceased the previous year, and administration of Norfolk Island was later transferred to Van Diemen's Land.

In 1850 the Australasian Anti-Transportation League was formed to lobby for the permanent cessation of transportation, its aims being furthered by the commencement of the Australian gold rushes the following year.

The last convict ship to be sent from England, the St. Vincent, arrived in 1853, and on 10 August Jubilee festivals in Hobart and Launceston celebrated 50 years of European settlement with the official end of transportation.

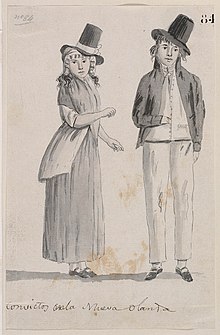

Convicts were made up of English and Welsh (70%), Irish (24%), Scottish (5%), and the remaining 1% from the British outposts in India and Canada, Maoris from New Zealand, Chinese from Hong Kong, and slaves from the Caribbean.

Born in Birmingham in 1841, he was transported to Western Australia in 1866 after deliberately committing a crime – setting fire to a haystack – in order to escape homelessness.

It is known as "Our Country's Good", based on the now-famous closing stanza: The poems of Frank the Poet are among the few surviving literary works done by a convict while still incarcerated.

A version of the convict ballad "Moreton Bay", detailing the brutal punishments meted out by commandant Patrick Logan and his death at the hands of Aborigines, is also attributed to Frank.

The ballad "Botany Bay", which describes the sadness felt by convicts forced to leave their loved ones in England, was written at least 40 years after the end of transportation.

The first convict film was a 1908 adaptation of Marcus Clarke's For the Term of His Natural Life, shot on location at Port Arthur with an unheard-of budget of £7000.

Other early titles include Sentenced for Life, The Mark of the Lash, One Hundred Years Ago, The Lady Outlaw and The Assigned Servant, all released in 1911.