Convoy PQ 11

[1] Before September 1941 the British had dispatched 450 aircraft, 22,000 long tons (22,000 t) of rubber, 3,000,000 pairs of boots and stocks of tin, aluminium, jute, lead and wool.

The USSR turned out to lack the ships and escorts and the British and Americans, who had made a commitment to "help with the delivery", undertook to deliver the supplies for want of an alternative.

The main Soviet need in 1941 was military equipment to replace losses because, at the time of the negotiations, two large aircraft factories were being moved east from Leningrad and two more from Ukraine.

The Anglo-Americans also undertook to send 42,000 long tons (43,000 t) of aluminium and 3, 862 machine tools, along with sundry raw materials, food and medical supplies.

[2] The growing German air strength in Norway and increasing losses to convoys and their escorts, led Rear-Admiral Stuart Bonham Carter, commander of the 18th Cruiser Squadron, Admiral sir John Tovey, Commander in Chief Home Fleet and Admiral Sir Dudley Pound the First Sea Lord, the professional head of the Royal Navy, unanimously to advocate the suspension of Arctic convoys during the summer months.

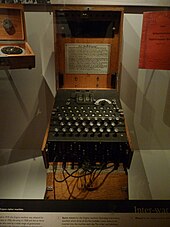

[3] The British Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS) based at Bletchley Park housed a small industry of code-breakers and traffic analysts.

By June 1941, the German Enigma machine Home Waters (Heimish) settings used by surface ships and U-boats could quickly be read.

In 1941, B-Dienst read signals from the Commander in Chief Western Approaches informing convoys of areas patrolled by U-boats, enabling the submarines to move into "safe" zones.

[6] In early September, Finnish Radio Intelligence deciphered a Soviet Air Force transmission which divulged the convoy itinerary, which was forwarded to the Germans.

[8] In winter, polar ice can form as far south as 50 mi (80 km) off the North Cape and in summer it can recede to Svalbard.

British convoys to Russia had received little attention since they averaged only eight ships each and the long Arctic winter nights negated even the limited Luftwaffe effort that was available.

Fliegerführer Stavanger (Air Commander Stavanger) the centre and north of Norway, Jagdfliegerführer Norwegen (Fighter Leader Norway) commanded the fighter force and Fliegerführer Kerkenes (Oberst [colonel] Andreas Nielsen) in the far north had airfields at Kirkenes and Banak.

[16] In large convoys, the commodore was assisted by vice- and rear-commodores with whom he directed the speed, course and zig-zagging of the merchant ships and liaised with the escort commander.

Oxlip had been on a Patrol White in the Denmark Strait and then refuelled in Seyðisfjörður on the east coast of Iceland to sail to meet Convoy PQ 11, which looked like "an undistinguished collection of grey-hulled ships low in the water".

The convoy was escorted by two destroyers, Airedale and Middleton, the two corvettes and the Anti submarine warfare (ASW) Trawlers Blackfly, Cape Argona and Cape Mariato until 17 February and the minesweepers Niger (Senior Officer Escort) and Hussar, Sweetbriar joined on 17 February when the first relay departed.

[22] The convoy managed an average of 8 kn (15 km/h; 9.2 mph) in cloud, fog and gales, spray freezing on the superstructures of the ships.

As soon as there was a lull in a storm the crews cleared the ice with steam hoses, picks and shovels to prevent the ships from becoming top-heavy.

The close convoy escort was to be reinforced, Coastal Command would increase its reconnaissance of the fiords around Trondheim to supplement the watch being kept by submarines and long-range Liberator patrols would be flown to the north-east from Iceland.