Corporate average fuel economy

The original CAFE standards sought to drive automotive innovation to curtail fuel consumption, and now the aim is also to create domestic jobs and cut global warming.

[5] The Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), as amended by the 2007 Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA), requires that the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) establish standards separately for passenger automobiles (passenger cars) and nonpassenger automobiles (light trucks) at the maximum feasible levels in each model year, and requires that DOT enforce compliance with the standards.

In addition, a Gas Guzzler Tax is levied on individual passenger car models (but not trucks, vans, minivans, or SUVs) that get less than 22.5 miles per US gallon (10.5 L/100 km).

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA) regulates CAFE standards and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) measures vehicle fuel efficiency.

[14] [failed verification] Furthermore, despite general opinion that larger and heavier (and therefore relatively fuel-uneconomical) vehicles are safer,[15] the U.S. traffic fatality rate—and its trend over time—is higher than some other western nations, although it has recently started to gradually decline at a faster rate than in previous years.

The traditional U.S. manufacturers, Chrysler, Ford, and General Motors, increased their fleet average fuel economy by 4.1 miles per gallon since 1980 according to the government figures.

[31] For the 2014 model year, Mercedes SUVs followed by GM and Ford light trucks had the lowest fleet average while Tesla followed by Toyota and Mazda had the highest.

[7] Before the oil price increases of the 2000s, overall fuel economy for both cars and light trucks in the U.S. market reached its highest level in 1987, when manufacturers managed 26.2 mpg (8.98 L/100 km).

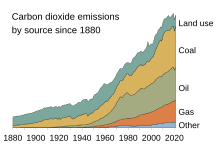

The United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit agreed with NHTSA that economic benefit-cost analysis (maximizing net economic benefits to the Nation) is, under the Energy Policy and Conservation Act (EPCA), an appropriate method to select the maximum feasible stringency of CAFE standards, but nonetheless found that NHTSA incorrectly set a value of zero dollars to the global warming damage caused by CO2 emissions; failed to set a "backstop" to prevent trucks from emitting more CO2 than in previous years; failed to set standards for vehicles in the 8,500 to 10,000 lb (4,500 kg) range; and failed to prepare a full Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) rather than a more abbreviated environmental impact assessment.

[32] In 2007, the House and Senate passed the Energy Independence and Security Act (EISA) with broad support, setting a goal for the national fuel economy standard of 35 miles per gallon (mpg) by 2020 and rendering the court judgment obsolete.

[34] However, the equation used to calculate the fuel economy target had a built in mechanism that provides an incentive to reduce vehicle size to about 52 square feet (the approximate midpoint of the current light truck fleet.

To achieve the target of 35mpg authorized under EISA for the combined fleet of passenger cars and light truck for MY2020, NHTSA is required to continue raising the CAFE standards.

[36] This latter allowance has drawn criticism from the UAW which fears it will lead manufacturers to increase the importation of small cars to offset shortfalls in the domestic market.

On April 22, 2008, NHTSA responded to the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 with proposed new fuel economy standards for cars and trucks effective model year 2011.

The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration has done significant work that will position the next Transportation Secretary to finalize a rule before the April 1, 2009 deadline."

"These standards are important steps in the nation's quest to achieve energy independence and bring more fuel efficient vehicles to American families", said Secretary LaHood.

Ten car companies and the UAW embraced the national program because it provided certainty and predictability to 2016 and included flexibilities that would significantly reduce the cost of compliance.

The policy was expected to result in yearly 5% increases in efficiency from 2012 through 2016, 1.8 billion barrels (290,000,000 m3) of oil saved cumulatively over the lifetime of the program and significant reductions in greenhouse gas emissions equivalent to taking 177 million of today's cars off the road.

[46] On July 29, 2011, President Obama announced an agreement with thirteen large automakers to increase fuel economy to 54.5 miles per gallon for cars and light-duty trucks by model year 2025.

The largest trucks carry almost no burden for the 2017–2020 timeframe, and are granted numerous ways to mathematically meet targets in the outlying years without significant real-world gains.

On July 18, 2016, the EPA, NHTSA and the California Air Resources Board (CARB) released a technical paper assessing whether or not the auto industry would be able to reach the 2022 to 2025 mpg standards.

It proposed freezing the fuel economy goals to the 2021 target of 37 mpg, would halt requirements on the production of hybrid and electric cars, and would eliminate the legal waiver that allows states like California to set more stringent standards.

[60] Researchers described in a December 2018 article in Science fundamental flaws and inconsistencies in the analysis justifying the proposed rule including miscalculating changes in the size of the automobile fleet and ignoring international benefits of reduced greenhouse gas emissions, thereby discarding at least $112 billion in benefits, and also by overestimating compliance costs and characterized such changes in the Notice of Proposed Rulemaking as misleading.

[citation needed] Economic research in 2015 concludes that firms are shown to be more incentivized toward innovations on fuel economy while the expenses of other safety considerations are undetermined.

[citation needed] In the May 6, 2007, edition of Autoline Detroit, GM vice-chairman Bob Lutz, an automobile designer/executive of BMW and Big Three fame, asserted that the CAFE standard was a failure and said it was like trying to fight obesity by requiring tailors to make only small-sized clothes.

[82][83] To overcome this fact, Congress enacted The Alternative Motor Fuels Act (AMFA) in 1988 to gain CAFE credits for the manufacture of flexible-fuel vehicles.

[86] Volkswagen embraced the rising CAFE standards and tailored its US product line with a fleet of economical, popular, inexpensive diesel vehicles, beginning in 2009.

[93][94][95][96] In 2003, Alliance of Automobile Manufacturers spokesman Eron Shosteck noted that automakers produce more than 30 models rated at 30 mpg or more for the U.S. market, and they are poor sellers, indicating that consumers do not prioritize fuel economy.

[110] John DeCicco, the automotive expert for the Environmental Defense Fund (EDF), estimated that this results in about 20% higher actual consumption than measured CAFE goals.

In fact, in 2015 Congress required federal agencies to adjust civil penalties for inflation (Public Law 114–74) and NHTSA under Heidi King unlawfully delayed its implementation.