Corsairs of Algiers

They were an ethnically mixed group of seafarers, including mostly "renegades" from European provinces of the Mediterranean and the North Sea, along with a minority of Turks and Moors.

The corsair taifa of Algiers reached the zenith of its power in the first half of the seventeenth century as an Ottoman military elite, theoritically.

Often former Christian slaves were promoted up the ta'ifa chain of command, the admirals and their corsairs were a powerful military and political force in the regency of Algiers, and could even challenge the authority of the Pasha and the Odjak Janissary corps.

Enriching those who cared for it and returning to the treasury one-fifth of its takings, the corso effectively created the state of Algiers,[4] and was essential to its existence, which all the efforts of the government tended to develop.

[6][7] Irish lawyer Charles Molloy wrote in 1682 regarding those shifts in dealing with: "Pirates that have reduced themselves into a Government of State, as those of Algier, Sally, Tripoli, Tunis, and the like" and should not "obtain the rights of solemnities of war."

[10] French historian Dianel Panzac, although admitting that the Barbary corsairs hardly differed in their methods from pirates that were still distinguishable by their "black flag, uncertain nationality, the vandalising of the ship, and especially the killing of the crew in order to leave no trace", nevertheless respected the administrative and diplomatic frameworks that North African regencies were bounded with, which is why the Barbary warships were classified as privateering vessels and not pirate ships.

The sultan expected obedience from the ruler, particularly in matters of foreign policy; an annual financial tribute to Istanbul; and ships and men for his fleets when they were demanded.

From the 16th century on, the growing volume of international trade, the succession of political crises leading to armed conflicts, the territorial appetites of certain states and the tendencies towards hegemony in the Mediterranean made the constitution and maintenance of an active navy essential, capable of defending a determined policy, which could be comprised as maintaining the following:[4] The ruler would be guided by a Divan - a council of government - while another council known as a tai'fa was charged with naval or privateering matters.

The ruler was also advised by an Agha, or commander-in- chief of the Algerian Janissary Odjak, whose duties included the annual collection of taxes and ensuring the security of the regency.

[12] In theory the same draconian system applied to the regency's ships and privateers when they were at sea; but in practice, the Kapudan Rais, the tai'fa, and individual captains were largely left to govern their own affairs.

[16] While the original holders of the title of Kapudan Rais were usually Turks or leading local privateers, by the 17th century the post was frequently held by a European renegade.

[17] The Kapudan Rais had a headquarters building near the harbour, and from there he and a small staff of clerks supervised the movement of all merchant shipping, as well as the activities of privateers and any regency warships.

Before a privateering captain could put to sea he had to obtain permission to sail from the Kapudan Rais, and collect a renewed letter of marque from the ' tai'fa.

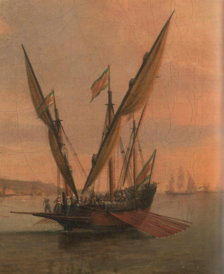

If the vessel was a galley] or galiot, however, the lack of space for water, provisions, captives or plunder meant that cruises were of fairly short duration.

Once these permissions were granted the captain hoisted a green flag to indicate that he was about to sail on a corso, and his crew would embark, accompanied in many cases by a detachment of the regency's Janissaries.

More than two thirds of the Algiers galiots were commanded by European renegades (six Genoese, two Venetians, two Albanians, three Greeks, two Spaniards, one Frenchman, one Hungarian, one Sicilian, one Neapolitan, one Corsican and three of their sons).

[24][25] A contemporary letter stated: "The infinity of goods, merchandise jewels and treasure taken by our English pirates daily from Christians and carried to Algire and Tunis to the great enriching of Mores and Turks and impoverishing of Christians"The Algerians armed for war the captured merchant ships which seemed fit for the corso, and also bought ships in Europe.

The masts, yards, sails, ropes, powder, ammunition, and artillery pieces, were supplied by the government of the Ottoman Porte and by certain minor powers of Europe, the latter in the form of tribute.

The Spanish watch towers and defense networks could not hold off the corsairs in Cullera and Villajoyosa, and so the tierras maritimas (coastal lands) were abandoned.

Attacks on Christian and especially Catholic shipping, with slavery for the captured, became prevalent in Algiers and were actually the main industry and source of revenues of the Regency.

[34]The severe discipline and care, made the Algiers galley a war instrument of the first order; the damage that the rais caused the enemies of the Ottoman sultan was so significant that Spanish Benedictine and historian Diego Haëdo wrote:[35] Sailing without any fear, they travel the sea from east to west, making fun of our galleys, whose crews, meanwhile, enjoy banqueting in the ports.

Knowing well that when their galiotes, so well equipped, so light, encounter the Christian galleys, so heavy and so crowded, the latter cannot think of giving chase, and preventing them from pillaging and stealing at will.

At a signal from the Sultan, they were seen running forward and fighting in the front ranks, as in Bejaïa, Malta, Lepanto and Tunis, where they acquired the well-deserved reputation of being the best and bravest sailors in the Mediterranean.

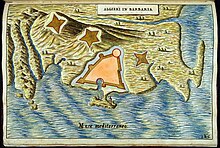

In 1529, Hayreddin Barbarossa seized the Peñon facing the city of Algiers from the Spanish and linked the rock to the port by building a pier.

[45] This domination enabled him to repel several attacks from a number of European countries, in particular, in October 1541, that of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, whose troops were defeated by the forces of the regency under the command of Hassan Agha, well aided by a storm which destroyed a good part of the enemy fleet.

Hayreddin and his successors rebuilt the wall surrounding the town, 36 t42 feet high, and some one and a half miles in length, of unbaked brick bonded with good mortar, resting on a substructure of concrete.

On the landward side the approaches to the town were defended by the fort known as the 'Star', built above the kasbah in 1568, and the Emperor Fort (Sultan Kalassi) built facing south between 1545 and 1580 on the site of the camp of Charles V.[48] In the confined space enclosed within the walls white houses were grouped closely together with terraces rising in tiers, their overhanging canopies supported on beams jutting so far out over the narrow streets as to sometimes meet those across the way, thus forming a ceiling of corduroy or of groined vaulting.

The slaves not chosen by the pasha were led into the Badestan, a long street closed at both ends, located on the site of the current Mahon square in Algiers.

[50] Until the use of round vessels in the 17th century, which did away with oars, the rais composed the crews of their galleys, which were generally very low in the water, with slaves they bought for this purpose, or captured at sea or on the Christian coasts.

When, at the beginning of the 17th century, sail became the only form of navigation, the use of slaves on corso ships diminished notably; but the raïs still employed a few for heavy work: turning the capstan, towing other boats, cleaning and so on.