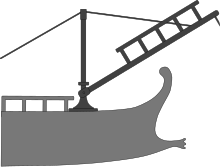

Corvus (boarding device)

There was a heavy spike shaped like a bird's beak on the underside of the device, which was designed to pierce and anchor into an enemy ship's deck when the boarding bridge was lowered.

This allowed a firm grip between the vessels and a route for the Roman legionaries (who served as specialized naval infantry called marinus) to cross onto and capture the enemy ship.

The boarding bridge allowed the Romans to use their infantry advantage at sea, therefore helping to overcome the Carthaginians' superior naval experience and skills.

[1] The added weight on the prow may have also compromised the ship's navigability, and it has been suggested that this instability led to Rome losing almost two entire fleets during storms in 255 and 249 BCE.

JW Bonebakker, formerly Professor of Naval Architecture at TU Delft, used an estimated corvus weight of one ton to conclude that it was "most probable that the stability of a quinquereme with a displacement of about 250 m3 (330 cu yd) would not be seriously upset" when the bridge was raised.

As Rome's ship crews became more experienced, Roman naval tactics also improved; accordingly, the relative utility of using the corvus as a weapon may have diminished.

By 36 BCE, at the Battle of Naulochus, the Roman navy had been using a different kind of device to facilitate boarding attacks, a harpoon and winch system known as the harpax, or harpago.

[4] The German classical scholar Wilhelm Ihne proposed another version of corvus that resembled Freinsheim’s crane with adjustments in the lengths of the sections of the bridge.

The design suggested by de St. Denis, however, did not include an oblong hole and forced the bridge to travel up and down the mast completely perpendicular to the deck at all times.

Wallinga's design included the oblong notch in the deck of the bridge to allow it to rise at an angle by the pulley mounted on the top of the mast.