Timbisha

The band traditionally was very small in size, and linguists estimate that fewer than 200 individuals ever spoke Panamint Shoshone.

For example, they traded with the Chumash people, then located in present-day Ventura, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo counties.

White settlers, using their knowledge of law, gained title to the Valley's scarce water and other resources, pushing the native Shoshones to inferior lands.

Belatedly, the Bureau of Indian Affairs did help Hungry Bill patent 160 acres of land in a canyon bordering Death Valley in 1908.

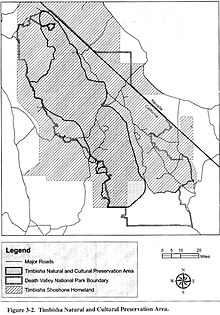

In 1933 President Herbert Hoover created Death Valley National Monument, an action that subsumed the tribe's homeland within park boundaries.

After unsuccessful efforts to remove the band to nearby reservations, National Park Service officials entered into an agreement with tribal leaders to allow the Civilian Conservation Corps to construct an Indian village for tribal members near park headquarters at Furnace Creek in 1938.

The Death Valley south of Furnace Creek, California, and the Panamint Valley south of Ballarat, California were predominantly "Desert Kawaiisu", the adjoining areas to the north were composed of almost equal numbers of Timbisha (Panamint) Shoshone and "Desert Kawaiisu" (Julian Steward, 1938).

Significantly, when borderlands were occupied, it was in fact common that settlements would include people speaking related but different languages.The decade of the 1950s was the height of the federal "Termination Era" when Congress sought to end its relationship with indigenous tribes by terminating their governments and trust protected tribal lands.

During this period, National Park Service officials began efforts to evict the Shoshones from Indian Village.

The service had previously forbidden Shoshones from continuing their traditional subsistence practices, including gathering firewood, plants, and hunting within Monument boundaries.

Using these conditions as a rationale, in 1957 the Park Service began a de facto removal policy for the Timbisha Shoshones still living in Indian Village.

[8] In 1958, Congress terminated "Indian Ranch", the enclave established for Panamint Bill earlier in the century and a place where some Timbisha Shoshone continued to reside.

By the late 1960s the Park Service began destroying Indian Village houses once residents had failed to pay rents or had stayed away for long periods; it did so by using high powered hoses to wash down the adobe casitas.

The band was able to secure a Bureau of Indian Affairs loan for several trailers to replace the decaying casitas at the village.

During this time, the Park Service resisted efforts by tribal members to build permanent houses at the site.

In 1979, with help from NARF, the Timbisha Shoshone band wrote and presented a petition for full federal tribal acknowledgment to the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

[9] With the help of the California Indian Legal Services, Timbisha Shoshone members led by Pauline Esteves and Barbara Durham began agitating for a formal reservation in the 1960s.

[10] In this effort, they were one of the first tribes to secure tribal status through the Bureau of Indian Affairs' Federal Acknowledgment Process.

Sometimes they used even Tsakwatan Tükkatün (″Chuckwalla Eaters″) as a self designation (actually pejorative term which is a loan translation from the Mono people for the Timbisha Shoshone).

Their Western and Northern Shoshone kin were called Sosoniammü Kwinawen (Kuinawen) Nangkwatün Nümü ("Shoshoni speaking northwards people").