Costume design

During the Late Middle Ages in Europe, dramatic enactments of Bible stories were prevalent, therefore actual Christian vestments, stylized from traditional Byzantine court dress, were worn as costumes to keep the performances as realistic as possible.

The costumes could be divided into five categories: "Ancient", which was out of style clothing used to represent another period; "Antique", older additions to contemporary clothing to distinguish classical characters; Dreamlike, "fanciful" garments for supernatural or allegorical characters; "Traditional" clothing which represented only a few specific people, such as Robin Hood, or "National or Racial" costumes that were intended to set apart a specific group of people but did not tend to be historically accurate.

Her practice soon became standard for all tragic heroines" [5] Major actors began to compete with one another about who would have the most lavish stage dress.

[6] In August 1823, in an issue of The Album, James Planché published an article saying that more attention should be paid to the time period of Shakespeare's plays, especially when it comes to costumes.

He observed to Charles Kemble, the manager of Covent Garden, that "while a thousand pounds were frequently lavished upon a Christmas pantomime or an Easter spectacle, the plays of Shakespeare were put upon the stage with makeshift scenery, and, at the best, a new dress or two for the principal characters.

[9] Planché had little experience in this area and sought the help of antiquaries such as Francis Douce and Sir Samuel Meyrick.

The research involved sparked Planché's latent antiquarian interests; these came to occupy an increasing amount of his time later in life.

[10] Despite the actors' reservations, King John was a success and led to a number of similarly costumed Shakespeare productions by Kemble and Planché (Henry IV, Part I, As You Like It, Othello, Cymbeline, Julius Caesar).

Planché also wrote a number of plays or adaptations which were staged with historically accurate costumes (Cortez, The Woman Never Vext, The Merchant's Wedding, Charles XII, The Partisans, The Brigand Chief, and Hofer).

[12] In 1923 the first of a series of innovative modern dress productions of Shakespeare plays, Cymbeline, directed by H. K. Ayliff, opened at Barry Jackson's Birmingham Repertory Theatre in England.

The standard items consist of at least 300 pieces and indicate the actors character type, age and social status through ornament, design, color and accessories.

"Color is always used symbolically: red for loyalty and high position, yellow for royalty, and dark crimson for barbarians or military advisors.

In Kabuki, another form of Japanese theatre, actors do not wear masks but rely heavily on makeup for the characterizations.

Traditionally, theater costumers were manually crafted by hand, through sewing and patterns drafted on paper.

[17] Utilizing 3D costume-modeling programs and 3D printers allows designers to come up with the most efficient ways to save the amount of materials used on a project.

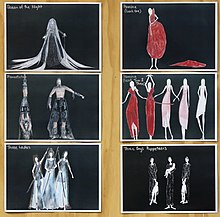

Costume designers usually begin with research where they find resources to establish the world where the play takes place.

Beginning with very quick rough sketches the designer can get a basic idea for how the show will look put together and if the rules of the world are being maintained.

[21] Draping involves manipulating a piece of fabric on a dress form or mannequin that has measurements closely related to the actor's.

It is a process that takes a flat piece of cloth and shapes it to conform the fabric to a three-dimensional body by cutting and pinning.