Issues affecting the single transferable vote

There are a number of complications and issues surrounding the application and use of single transferable vote proportional representation that form the basis of discussions between its advocates and detractors.

Among electorates considering the adoption of STV, there is frequently expressed concern that PR-STV is relative complex compared with plurality voting methods and is little understood.

For example, polls conducted in 2005 at the time when the Canadian province of British Columbia held a referendum on adopting BC-STV, when "no" voters were asked why they were voting against STV, they gave their reason as "wasn't knowledgeable".

STV detractors see that as a flaw, arguing that political parties should be able to structure public debate, mobilize and engage the electorate, and develop policy alternatives.

This incentive to attain first preferences, in turn, may lead to a strategy of candidates placing greater importance on a core group of supporters.

There are also tactical considerations for political parties in the number of candidates they stand in an election where full ranking on the ballots is not required.

In the Republic of Ireland, the main political parties usually give careful consideration as to how many candidates to put forward in the separate Dáil (parliamentary) districts.

The larger the number of members returned by a district, the greater the chance that a voter that changes their vote can influence the outcome of the election.

To prevent exhausted ballots, some PR-STV systems oblige voters to give a complete ordering of all of the candidates in an election.

Some jurisdictions compromise by setting a minimum number of preferences that must be filled for a ballot paper to be valid (semi-optional preferential voting).

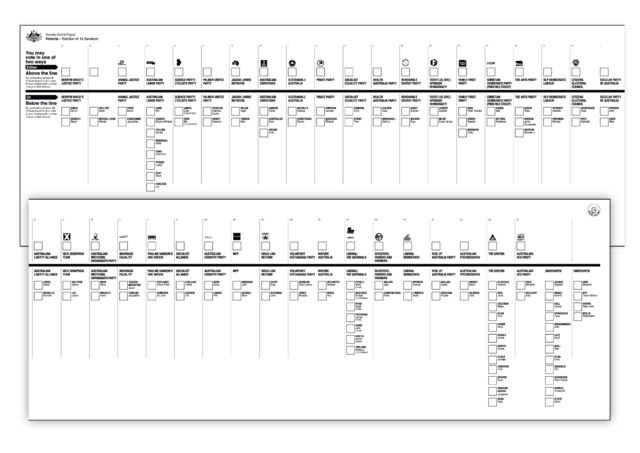

To make it easy to create what is called a complete ballot, some PR-STV systems provide the option of using group voting tickets rather than the voter having to mark manually a long list of individual preferences.

[6] In 2016 group tickets were abolished to avoid undue influence of preference deals[7] and a form of optional preferential voting was introduced.

Voters are instructed to number at least their six most-preferred party slates; however, a "savings provision" is in place to ensure that ballots will still be counted if less than six are given.

The effect seems to be minimal, as the Dáil median surname currently falls within the letter K, which accurately reflects the distribution of Irish names.

If they wish to support other candidates of the same party, but have no strong preference between them, the voter is likely to number them downwards from the top of the ballot sheet, in normal reading fashion.

Each of Australia's states are strongly urbanised to a similar (~75% or more), and so rural-urban political divides are similar in each state, resulting in a fairly proportional composition The New South Wales Legislative Council avoids the use of districts entirely, electing 21 members (half of the Council) at a time using a single, statewide at-large constituency and guaranteeing results that are proportional to the final allocation of preferences.

The Western Australian Legislative Council is intentionally malapportioned to give half the seats to non-Perth (largely and remote) areas despite having only 35% of the WA population.

However this method of estimation may be inaccurate due presence o independent candidates and of cross-party voting shown by backup preferences (uncertainty as to which party voter supports most strongly).

Voting patterns have shown that most voters stay with their chosen party within a limited percentage range based on local issues and circumstances.

This can also be observed in Australian Senate representation for the Northern Territory; where the territory's two senators have been divided by the two major parties, bipartisan but uncompetitive representation by design[12] A larger number of candidates elected also results in a smaller number of wasted votes on the final count.

However, larger districts and the implicit larger number of candidates also increase the difficulty of giving meaningful rankings to all candidates from the perspective of the individual voter, and may result in increased numbers of exhausted ballots and reliance on party labels or group voting tickets.

They found "a larger district magnitude is shown to have positive effects in relation to the representation of women and minorities, as well as allowing for a plurality of ideas in terms of policy."

In theory, STV ensures the election of particularly small minorities provided they secure a quota's worth of votes, if very large districts were used.

In State of Victoria (Australia) 40 members are elected for the Legislative Council, five per district through STV, with 3.1M votes cast in 2006.

The Meek system, which is immune to this strategy, elects A, B and D. Under SGT, the E > A > C > D voters effectively determine the winners of the two final seats.

Failure to satisfy independence of irrelevant alternatives makes STV slightly prone to strategic nomination, albeit less so than with plurality methods where the spoiler effect is more pronounced and predictable.

Borda counts include deeper preferences, and so contain more information than is held in current first place votes.

Elimination by Borda counts creates other features for STV including promotion of moderate candidates and increased stability in the face of small changes of preferences.

When compared with other voting methods, the question of how to fill vacancies which occur under STV can be difficult given the way that results depend upon transfers from multiple candidates.

In a recent review of the City of Melbourne, in Australia, the cost of holding a by-election for a single casual vacancy was estimated to surpass $1 million.