Counter-battery radar

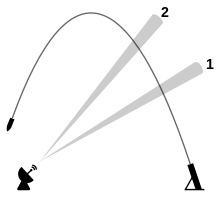

Early counter-battery radars were generally used against mortars, whose lofted trajectories were highly symmetrical and allowed easy calculation of the launcher's location.

Starting in the 1970s, digital computers with improved calculation capabilities allowed more complex trajectories of long-range artillery to also be determined.

[1]: 5–15 With the aid of modern communications systems, the information from a single radar can be rapidly disseminated over long distances.

The emergence of indirect fire in World War I saw the development of sound ranging, flash spotting and aerial reconnaissance, both visual and photographic.

Generally, the shells could not be seen directly by the radar, as they were too small and rounded to make a strong return, and travelled too quickly for the mechanical antennas of the era to follow.

Radar operators in light anti-aircraft batteries close to the front line found they were able to track mortar bombs.

These accidental intercepts led to their dedicated use in this role, with special secondary instruments if necessary, and development of radars designed for mortar locating.

By the early 1970s, radar systems capable of locating guns appeared possible, and many European members of NATO embarked on the joint Project Zenda.

This was short-lived for unclear reasons, but the US embarked on its Firefinder program and Hughes Aircraft Company developed the necessary algorithms, although it took two or three years of difficult work.

The next step forward was European when in 1986 France, West Germany and UK agreed the 'List of Military Requirements' for a new counter-battery radar.

[2] 29 COBRA systems were produced and delivered in a roll-out which was completed in Aug. 2007 (12 to Germany – out of which two were re-sold to Turkey, 10 to France and 7 to the UK).

In another back to the future step it has also proved possible to add counter-battery software to battlefield airspace surveillance radars.

Once phased array radars compact enough for field use and with reasonable digital computing power appeared, they offered a better solution.

A phased array radar has many transmitter/receiver modules which use differential tuning to rapidly scan up to a 90° arc without moving the antenna.

However, with these figures, long range accuracy may be insufficient to satisfy the rules of engagement for counter-battery fire in counter insurgency operations.

This is usually for intelligence purposes because it is seldom possible to give the target sufficient warning time in a battlefield environment, even with data communications.

The new lightweight counter-mortar radar (LCMR – AN/TPQ 48) is crewed by two soldiers and designed to be deployed inside forward positions.

Similarly the new GA10 (Ground Alerter 10)[6] radar was qualified and successfully deployed by the French land forces in 2020 in several different FOBs worldwide.

The consequences of this detection are likely to be attack by artillery fire or aircraft, including anti-radiation missiles, or electronic countermeasures.

Counter-battery radars operate at microwave frequencies with relatively high average energy consumption, up to the tens of kilowatts.