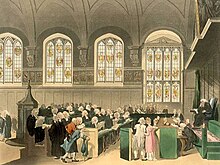

Court of Chancery

From the time of Queen Elizabeth I (r. 1558–1603) onwards the Court was severely criticised for its slow pace, large backlogs, and high costs.

[13] The chancellor and his clerks often heard the cases directly, rather than having them referred to the council itself; occasionally a committee of lay and church members disposed of them, assisted by the judges of the common law courts.

[15] The Chancery and its growing powers soon came to be resented by Parliament and the nobility; Carne says that it is possible to trace a general "trend of opposition" during the Plantagenet period, particularly from members of the clergy, who were more used to Roman law than equity.

He gives complaints about the perversion of justice in the common law courts, along with growing mercantile and commercial interests, as the main reason for the growth, arguing that this was the period when the Chancery changed from being an administrative body with some judicial functions to "one of the four central courts of the realm ... the growth in the number of [cases] is a primary indicator of the changing position of Chancery".

This had been vehemently opposed by the common-law judges, who felt that if the lord chancellor had the power to override their decisions, parties to a case would flock to the Court of Chancery.

[29] Coke and the other judges over-ruled this judgment while Ellesmere was ill, taking the case as an opportunity to completely overthrow the lord chancellor's jurisdiction.

[30] Both recommended a judgment in Ellesmere's favour, which the Monarch made, saying: as mercy and justice be the true supports of our Royal Throne; and it properly belongeth to our princely office to take care and provide that our subjects have equal and indifferent justice ministered to them; and that when their case deserveth to be relieved in course of equity by suit in our Court of Chancery, they should not be abandoned and exposed to perish under the rigor and extremity of our laws, we ... do approve, ratifie and confirm, as well the practice of our Court of Chancery.

In the late 17th century Robert Atkyns attempted to renew this controversy in his book An Enquiry into the Jurisdiction of the Chancery in Causes of Equity, but without any tangible result.

During the 16th century the Court was vastly overworked; Francis Bacon wrote of 2,000 orders being made a year, while Sir Edward Coke estimated the backlog to be around 16,000 cases.

[37] Parliament eventually proposed dissolving the court as it then stood and replacing it with "some of the most able and honest men", who would be tasked with hearing equity cases.

This was based on the code set by the Cromwellian Commissioners, and limited the fees charged by the court and the amount of time they could take on a case.

[43] Under Charles II, for the first time, there was a type of common law appeal where the nature of the evidence in the initial trial was taken into account, which reduced the need to go to the Court of Chancery.

For equity, the act provided that a party trying to have his case dismissed could not do so until he had paid the full costs, rather than the nominal costs that were previously required; at the same time, the reforms the act made to common-law procedure (such as allowing claims to be brought against executors of wills) reduced the need for parties to go to equity for a remedy.

[50] The recommendations were not immediately acted on, but in 1743 a list of permissible fees was published, and to cut down on paperwork, no party was required to obtain office copies of proceedings.

[52] The success of the Code Napoleon and the writings of Jeremy Bentham are seen by academic Duncan Kerly to have had much to do with the criticism, and the growing wealth of the country and increasing international trade meant it was crucial that there be a functioning court system for matters of equity.

Further structural reforms were proposed; Richard Bethell suggested three more vice-chancellors and "an Appellate Tribunal in Chancery formed of two of the vice chancellors taken in rotation", but this came to nothing.

[59] This did not save them, however; in 1842 the "nettle" of the Six Clerks Office was grasped by Thomas Pemberton, who attacked them in the House of Commons for doing effectively sinecure work for high fees that massively increased the expense involved in cases.

c. 87) gave all court officials salaries, abolished the need to pay them fees and made it illegal for them to receive gratuities; it also removed more sinecure positions.

He observed that at the time he was writing there was a case before the Chancery court "which was commenced nearly twenty years ago ... and which is (I am assured) no nearer to its termination now than when it was begun".

The lord chancellors during this period were more cautious, and despite a request by the lawyers' associations to establish a royal commission to look at fusion, they refused to do so.

The Master of the Rolls was transferred to the new Court of Appeal, the lord chancellor retained his other judicial and political roles, and the position of vice-chancellor ceased to exist, replaced by ordinary judges.

[75] The use of trusts and uses became common during the 16th century, although the Statute of Uses "[dealt] a severe blow to these forms of conveyancing" and made the law in this area far more complex.

[77] The Chancery's jurisdiction over "lunatics" came from two sources: first, the king's prerogative to look after them, which was exercised regularly by the lord chancellor, and second, the Lands of Lunaticks Act 1324 (Ruffhead: 17 Edw.

Due to the vested interest of the king (who would hold the lands) the actual lunacy or idiocy was determined by a jury, not by an individual judge.

[97] A statute passed during the reign of Richard II specifically gave the Chancery the right to award damages, stating: For as much as People be compelled to come before the King's Council, or in the Chancery by Writs grounded upon untrue Suggestions; that the Chancellor for the Time being, presently after that such Suggestions be duly found and proved untrue, shall have Power to ordain and award Damages according to his Discretion, to him which is so troubled unduly, as afore is said.

This was followed by Hatch v Cobb, in which Chancellor Kent held that "though equity, in very special cases, may possibly sustain a bill for damages, on a breach of contract, it is clearly not the ordinary jurisdiction of the court".

[107] According to William Carne, Thomas Egerton was the first "proper" lord chancellor from the Court of Chancery's point of view, having recorded his decisions and followed the legal doctrine of precedent.

[109] Following the dissolution of the Court of Chancery in 1873, the lord chancellor failed to have any role in equity, although his membership of other judicial bodies allowed him some indirect control.

In the early years they were almost always members of the clergy, called the "clericos de prima forma"; it was not until the reign of Edward III that they were referred to as Masters in Chancery.

was passed that year requiring that fees be paid directly into the Bank of England, and creating an Accountant-General to oversee the financial aspects of the court.