Crabeater seal

They are medium- to large-sized (over 2 m in length), relatively slender and pale-colored, found primarily on the free-floating pack ice that extends seasonally out from the Antarctic coast, which they use as a platform for resting, mating, social aggregation and accessing their prey.

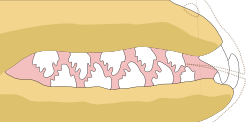

[2] This success of this species is due to its specialized predation on the abundant Antarctic krill of the Southern Ocean, for which it has uniquely adapted, sieve-like tooth structure.

Indeed, its scientific name, translated as "lobe-toothed (lobodon) crab eater (carcinophaga)", refers specifically to the finely lobed teeth adapted to filtering their small crustacean prey.

[4] These species, collectively belonging to the Lobodontini tribe of seals, share teeth adaptations including lobes and cusps useful for straining smaller prey items out of the water column.

The ancestral Lobodontini likely diverged from their sister clade, the Mirounga (elephant seals) in the late Miocene to early Pliocene, when they migrated southward and diversified rapidly in the relative isolation around Antarctica.

Together with the tight fit of the upper and lower jaw, a bony protuberance near the back of the mouth completes a near-perfect sieve within which krill are trapped.

[3] Crabeater seals have a continuous circumpolar distribution surrounding Antarctica, with only occasional sightings or strandings in the extreme southern coasts of Argentina, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

[3] They spend the entire year on the pack ice zone as it advances and retreats seasonally, primarily staying within the continental shelf area in waters less than 600 m (2,000 ft) deep.

[9] They colonized Antarctica during the late Miocene or early Pliocene (15–25 million years ago), at a time when the region was much warmer than today.

[3] Crabeater seals have a typical, serpentine gait when on ice or land, combining retractions of the foreflippers with undulations of the lumbar region.

[2] The most gregarious of the Antarctic seals, crabeaters have been observed on the ice in aggregations of up to 1,000 hauled out animals and in swimming groups of several hundred individuals, breathing and diving almost synchronously.

Carcasses have been found over 100 km (62 mi) from the water and over 1,000 m (3,300 ft) above sea level, where they can be mummified in the dry, cold air and conserved for centuries.

Indeed, first-year mortality is exceedingly high, possibly reaching 80%, and up to 78% of crabeaters that survive through their first year have injuries and scars from leopard seal attacks.

[22] The high predation pressure has clear impacts on the demography and life history of crabeater seals, and has likely had an important role in shaping social behaviors, including aggregation of subadults.

[23] While most predation occurs in the water, coordinated attacks by groups of killer whales creating a wave to wash the hauled-out seal off floating ice have been observed.